The Baal's Bridge Square (1517)

One of Masonry's oldest symbolical Masonic Relic, from the year 1517.

The Artifact as Historical Anomaly

The Baal's Bridge Square is arguably the single most important tangible artifact in the history of Irish Free-Masonry and remains one of the most significant and debated Masonic relics globally. Discovered in 1830 in the foundations of a medieval bridge in Limerick, Ireland, this small brass object, dated to the early 16th century, stands as a profound historical anomaly. Its existence provides compelling physical evidence that the philosophical, ethical, and symbolic—or "speculative"—elements of Free-Masonry were active and structured in Ireland centuries earlier than the established historiography, which largely traces the origins of modern speculative Masonry to the formation of the Grand Lodge of England in 1717, would traditionally suggest. The artifact fundamentally challenges prevailing timelines, suggesting the symbolic interpretation of Masonic tools and moral principles were "well-established in Ireland by the early 16th century".

Physical Profile and Material Analysis

The artifact is consistently described as an "ancient brass square". When it was recovered in 1830, its condition was recorded as "much eaten away" and "much corroded". This high degree of corrosion, a natural consequence of its 300-year entombment within a damp, riverside foundation, is a critical forensic detail. It is the primary cause of the subsequent academic and antiquarian debate regarding the precise legibility of its date and inscriptions. Despite this degradation, contemporary accounts noted that the "shape, size, and formation of the engraving on both sides were easily traced," allowing for its study.

A Jewel, Not a Tool

A meticulous analysis of the square's specific markings reveals that it was not intended as a simple operative stonemason's working tool, but rather as a piece of ceremonial regalia or a "jewel."

- The Master's Jewel: The artifact is explicitly described in historical Masonic analyses as being "identical to the Jewel of a Worshipful Master". This identification is paramount, as it implies the existence of a formal, hierarchical lodge structure with presiding officers, a purely speculative (non-operative) construct.

- Suspension Holes: The square possesses "two holes in each end". This detail is conclusive evidence of its function. These holes are "suspected to be for the purpose of hanging the square from a collar". A tool for drawing lines would have no need for such holes; an emblem of office, or jewel, would require them.

- Heart Symbology: A "heart" is engraved "in each angle" or "on each side on the outer angle" of the square. This is a purely symbolic, non-operative marking, reinforcing the speculative and moral nature of the artifact and directly linking to the inscription's themes of "love and care".

The physical form of the artifact, therefore, proves its speculative function. The identification as a "Master's Jewel" and the presence of suspension holes for wearing demonstrate it was an item of office. The existence of a "Master" implies the existence of a formal "Lodge" over which to preside. This act of wearing a symbolic jewel is a purely speculative custom, meaning the artifact's design, even before considering its inscription, demonstrates that a structured and symbolic form of Free-Masonry was in practice at the time of its creation.

Physical Profile of the Baal's Bridge Square

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Item | The Baal's (Ball's) Bridge Square |

| Material | Ancient Brass |

| Condition | "Much corroded," "much eaten away" |

| Date | Contested: 1507 (popularly accepted) or 1517 (forensically argued) |

| Inscription | "I will strive to live with love & care upon the level by the square" |

| Symbolic Markings | A heart in each angle; holes in each end for collar suspension |

| Identification | Jewel of a Worshipful Master |

| Current Custodian | Antient Union Lodge No. 13, Limerick, Ireland |

Unearthing History in the Foundations of Limerick (1830)

The 1830-1831 Rebuilding of Baal's Bridge

The square was discovered in November 1830. Its unearthing was not the result of a deliberate archaeological expedition but a fortunate byproduct of a major 19th-century civil infrastructure project. The "ancient bridge of four arches," which had stood for centuries, was being demolished to make way for a new, modern "single-arched hump-back limestone bridge". This project, commissioned by the New Limerick Navigation Company, was a significant undertaking to modernize the city's connection and improve the route to Dublin.

Brother James Pain, Architect

The artifact was found by "Brother James Pain". Pain was not a common laborer; he was a principal of the esteemed firm "J.A. & G. R. Pain Architects," the very firm that designed the new bridge. He was also acting as the "contractor for re-building Baal's Bridge".

Pain's status as a Free-Mason ("a brother") was a critical factor in the artifact's survival. It was noted as "very lucky" that the engineer on the job "would have instantly recognised the shape and inscription as something Masonic". Had he not, this priceless "treasurer" would almost certainly have been "thrown aside into the river as a piece of junk".

This event creates a powerful historical parallel: in 1830, a "Brother" (James Pain), engaged in the operative act of bridge-building, discovered a symbolic relic left by a 16th-century "Brother" who was engaged in the very same operative act on the very same site.

The North-East Corner

The square was recovered from a highly specific, and for Free-Masons, a symbolically critical location. Sources are precise: it was "dug out of the eastern corner of the foundation of the northern land pier". This pier was located on the "King's Island or English Town side" of the Abbey River.

This exact location corresponds to the North-East Corner. Within Masonic ritual, the North-East Corner is the traditional and ceremonial position for laying the first foundation stone of a new edifice. The convergence of the discovery's location with this ancient custom is not a coincidence. It provides irrefutable proof that the square's placement was a deliberate, ceremonial act. It was not a lost item; it was a ritual deposit, "a small offering or blessing for the work ahead". This conclusion is stated directly in the historical analysis: "The position in which the square was found indicates that one of our Masonic customs, still in vogue, was practiced in Ireland over 400 years ago".

"I Will Strive"

The Full Text of the Creed

Despite the heavy corrosion on the brass, the inscription was legible enough to be transcribed. The full text, etched onto the artifact, reads:

"I WILL STRIVE TO LIVE WITH LOVE & CARE UPON THE LEVEL BY THE SQUARE."

This sentence is not merely a motto; it is a complete, self-contained ethical creed, articulating a personal commitment to a moral life using the symbolic language of the Masonic craft.

Symbolic Deconstruction of the Speculative Language

The inscription's language is entirely speculative, applying philosophical meaning to the tools of an operative mason.

- "I will strive...": This opening phrase is profoundly significant. It is not a dogmatic commandment ("Thou shalt") but a statement of personal, ongoing moral endeavor. It places the responsibility for moral action squarely on the individual.

- "With Love & Care...": These words directly reflect the core Masonic tenets of Brotherly Love, Relief, and Truth. This textual message is physically reinforced by the "heart" symbols engraved on the square's angles.

- "Upon the Level...": This is a clear symbolic (not operative) reference to the Masonic ideal of equality, integrity, and dealing fairly with all people.

- "By the Square...": This is the ultimate Masonic emblem for morality, truthfulness, virtue, and "uprightness" of character. It signifies "squaring" one's actions with the principles of virtue.

The prevailing academic narrative of Free-Masonry has long posited a two-stage development: first, operative guilds of working stonemasons, followed by a 17th or 18th-century "transition" where "speculative" gentlemen joined these guilds and applied philosophical meanings to their tools. The Baal's Bridge Square, through its inscription, fundamentally "challenges this prevailing notion".

The language is purely moral. It proves, unequivocally, that the 16th-century operative Masons who built the original bridge were already in full possession of a rich, symbolic, and philosophical system. The "symbolic interpretation of Masonic tools" was not a later invention; it was concurrent with their operative work.

Furthermore, the specific phrasing "I will strive" resonates as a humanist and individualistic statement, perfectly at home in the intellectual climate of the Renaissance (early 16th century), which emphasized personal development and human potential. It marks a departure from a purely medieval, dogmatic adherence to external law, blending the technical world of the artisan with the emerging humanist philosophy of the individual.

The Academic Debate for the Date (1507 vs. 1517)

A Corroded Digit

A central academic controversy surrounds the artifact's exact date. The "much corroded" state of the brass has created ambiguity in the third digit of the date. The entire debate centers on whether this heavily "disfigured" numeral is a "0" or a "1".

The Competing Scholarly Arguments

The debate can be broken down into two main camps, supported by various antiquarians and researchers who have examined the relic or facsimiles.

- Camp 1: The "1517" Reading (Furnell, Crossle, Tatsch)

- Bro. Michael Furnell (1842): In his 1842 note for the Freemasons' Quarterly Review, Furnell, who produced the first published sketch, transcribed the date as 1517.

- Bro. Philip Crossle (1929): Writing in the respected The Builder magazine, Crossle reported conducting a "minute examination of the relic with a magnifying glass". He concluded that Furnell was correct, stating the third figure is "certainly intended for the figure one... formed in the old style, like the letter 'J'" and that the curve at the bottom had been mistaken for a "cipher" (a zero).

- Bro. J. Hugo Tatsch (1930): In a follow-up article in The Builder, Tatsch analyzed original correspondence related to the discovery. He concurred with Crossle, stating, "No doubt 1517" and noting that of the early brethren who examined it, "all were agreed that it is a figure '1'".

- Camp 2: The "1507" Reading (Berry and Popular Acceptance)

- H. F. Berry (1905): In his book The Marencourt Cup and Ancient Square, H. F. Berry disagreed with Furnell's 1842 reading and asserted the date was 1507.

- Popular Adoption: For reasons that may relate to precedent or the allure of an earlier date, Berry's 1507 reading "had been generally accepted on his authority". Consequently, the vast majority of modern, secondary sources, lodge websites, and historical summaries now cite 1507 as the definitive date.

The discoverer himself, James Pain, illustrated the difficulty in a letter, suggesting the date was "J5J7 or 5557" and admitting the third figure was so "disfigured that 'we cannot tell what it is'".

This reveals a clear disconnect between popular history and forensic scholarship. The 1507 date has become "fact" by sheer repetition. However, the most rigorous, hands-on analyses published in the 20th century (Crossle, Tatsch) argue forcefully for 1517. While 1507 is the famous date, 1517 appears to be the forensically stronger candidate.

Ultimately, while the 10-year discrepancy is critical for historiographical accuracy, it is irrelevant to the artifact's primary significance. Whether 1507 or 1517, the square is definitively a product of the early 16th century. Both dates serve as "compelling evidence" that "symbolic interpretation... and moral principles were already well-established" centuries before the formal Grand Lodge era. The core argument remains unchanged.

Chronology of the Date Controversy

| Year of Publication/Letter | Author/Source | Asserted Date | Key Rationale/Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1830 | Bro. James Pain (Discoverer) | "J5J7 or 5557" (Ambiguous) | Letter states, "Third figure... so disfigured" |

| 1842 | Bro. Michael Furnell | 1517 | First published sketch/note; cited as a "mistake" by Berry |

| 1905 | H. F. Berry | 1507 | Disagreed with Furnell; this date became "generally accepted" |

| 1929 | Bro. Philip Crossle | 1517 | "Minute examination with a magnifying glass"; "third figure... like the letter 'J'" |

| 1930 | Bro. J. Hugo Tatsch | 1517 | "No doubt 1517"; based on review of correspondence; "all were agreed that it is a figure '1'" |

A History of Baal's Bridge, Limerick

The Original Medieval "Bald Bridge"

The artifact's 300-year entombment began within the foundation of the original Baal's Bridge. This was a medieval "ancient bridge of four arches". It served a crucial strategic and civic role as the "only link before the mid-18th century" connecting the two distinct parts of medieval Limerick: "Englishtown" (on King's Island) and "Irishtown". Early drawings show it was a "living" bridge, with "a row of houses on the bridge" itself. Its original name was "The Bald Bridge," a name possibly derived from a "lack of parapets" in its early design. Town records confirm its existence in 1558, a date which aligns perfectly with a 1507 or 1517 construction date for its piers.

The 19th-Century Modernization (1830-1831)

The structure that stands today, and from whose predecessor the square was recovered, is a "single-arched hump-back limestone bridge". This was a major project of the "New Limerick Navigation Company," which was incorporated in 1830 with "Chas. Wye Williams Esqr." as its Chief Director. The architects were the firm of J.A. & G. R. Pain. The project timeline was swift and is precisely documented: demolition of the old bridge began in November 1830, and the new bridge was finished in November 1831. Plaques on the current bridge commemorate this construction and its architects.

The history of the bridge is a microcosm of Limerick's urban history. The old, house-covered, four-arch bridge represented the medieval, divided city. The new, sleek, 1831 single-arch bridge represented the modernization and unification of the city as part of a major 19th-century infrastructure push that "much improved" the "route eastwards towards Dublin". The discovery of the square is therefore a literal "unearthing" of the city's symbolic, medieval, and fraternal past during the very act of its industrial modernization.

Timeline of Baal's Bridge, Limerick

| Date / Period | Structure / Event |

|---|---|

| Early 16th c. (1507/1517) | Construction of the "ancient" bridge's foundation pier; ceremonial placement of the Square. |

| 1558 | "Ancient bridge of four arches" is documented in town records. |

| 16th-18th c. | Bridge serves as the only link between Englishtown and Irishtown, bearing a row of houses. |

| Nov 1830 | Demolition of the old bridge begins by J.A. & G. R. Pain. |

| Nov 1830 | The Baal's Bridge Square is discovered in the northern land pier foundation. |

| Nov 1831 | The new "single-arched hump-back" bridge is completed and opened. |

The Square's Impact on Masonic Historiography

An Artifact that Challenges Orthodoxy

The discovery of the Baal's Bridge Square is the "compelling evidence" that "the Craft was flourishing in Ireland in the 16th century". Its recovery "has had considerable influence on thinking regarding the dating of the earliest existence of Masonry in Ireland". It provides a tangible, physical counter-narrative to the long-held belief that speculative Free-Masonry was an 18th-century invention.

Date, Inscription, and Placement

The artifact's profound significance rests on three convergent lines of evidence, which, when taken together, are conclusive.

- The Date (Early 16th c.): The 1507/1517 date places it nearly 180 years before the earliest documented reference to Free-Masonry in Ireland (a letter from 1688). It predates the formation of the Grand Lodge of Ireland (c. 1725) by over 200 years.

- The Inscription (The Moralism): The purely speculative creed, "I will strive...", proves that the "application of moral principles" was not an 18th-century affectation but a fully formed system of ethics practiced by 16th-century Irish Masons.

- The Placement (The Ritual): The discovery in the North-East corner proves that specific and complex Masonic customs, such as the foundation stone ceremony, were being "practiced in Ireland over 400 years ago".

Collapsing the Operative/Speculative Divide

The most profound implication of the Baal's Bridge Square is its effective refutation of a strict, linear "operative-to-speculative" timeline. The individual who deposited the square was, by definition, an operative Mason engaged in the construction of a bridge. However, he was simultaneously a speculative Mason, performing a ritual, adhering to a complex moral creed, and likely holding the office of "Master" in a formal lodge.

This artifact proves that the two traditions were not sequential but were inextricably linked and co-existed from a much earlier period than previously believed.

This object re-centers a part of Masonic history in Ireland. While much 18th and 19th-century Masonic history is Anglo-centric (focused on London's 1717 Grand Lodge), the Baal's Bridge Square provides a tangible, dated object that establishes Ireland as a primary and independent locus for the development of speculative Free-Masonry. It lends powerful support to the claims of lodges like its custodian, Antient Union No. 13, to be "time immemorial," suggesting that Irish Masonry possessed a deep, independent, and philosophically advanced tradition long before the formal establishment of Grand Lodges. It is, as suggested, "the oldest masonic relic ever found in Ireland, and perhaps... anywhere".

The Custodianship and Legacy of the Square

Antient Union Lodge No. 13

The original, authentic Baal's Bridge Square is not on general public display. Due to its age, fragility, and immense historical value, it is "currently being preserved by Antient Union Lodge No. 13 in Limerick, Ireland". This lodge is the artifact's official custodian and has implemented "strict conservation measures" to safeguard it from further deterioration.

This custodianship is symbolically fitting. Antient Union Lodge No. 13 is itself described as a "time immemorial" lodge, meaning its own history is so ancient that "it was in existence prior to the existence of a Grand Lodge". There could be no more appropriate guardian for an artifact that proves the existence of such pre-Grand Lodge, "time immemorial" Free-Masonry. The lodge and the relic are two sides of the same coin of Irish Masonic antiquity; the lodge does not just preserve the relic, it validates the relic's claim, just as the relic validates the lodge's "time immemorial" status.

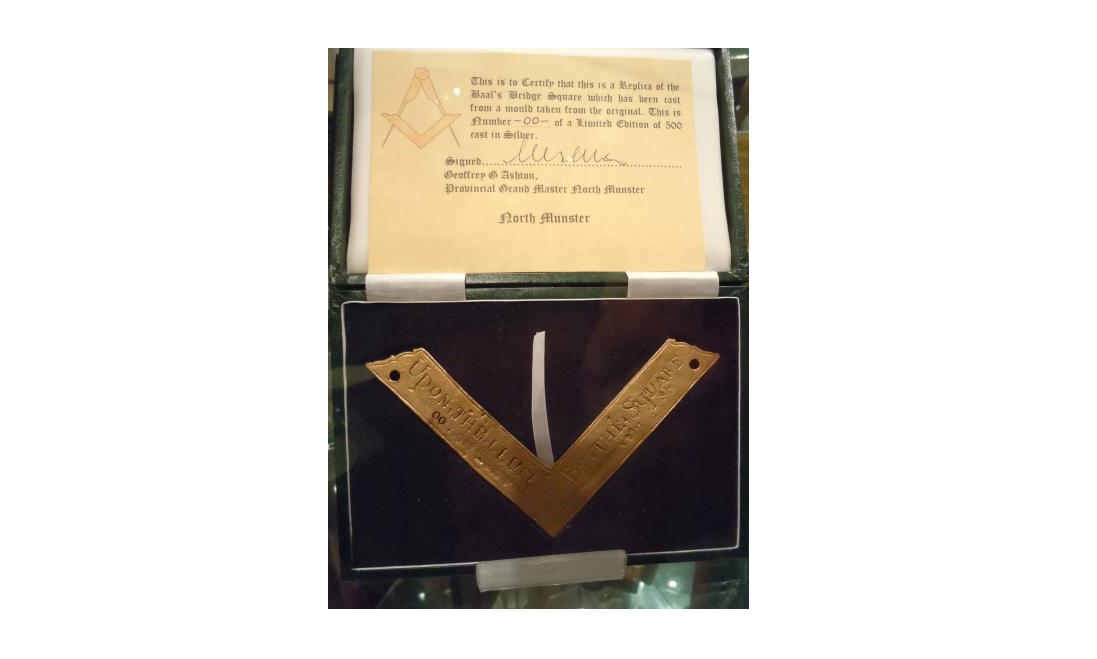

Replicas and Dissemination

While the original is carefully protected, the artifact's story and significance are shared with the public through high-quality replicas.

- A prominent replica "takes pride of place in the new museum" at The Masonic Centre in Limerick. This centre is located near King John's Castle, overlooking the River Shannon, "not far from where the Square was first discovered".

- In 2002, a project created meticulous silver replicas to "commemorate the 160th anniversary of the founding of the Provincial Grand Lodge of North Munster". These replicas were made available for purchase, allowing "Masonic enthusiasts worldwide to forge a tangible connection with this ancient artifact" and its enduring symbolism.

The Baal's Bridge Square endures as a "powerful symbol". As a historical document, it has successfully challenged and rewritten the timeline of the Masonic craft, proving its deep speculative roots in 16th-century Ireland. As a cultural relic, its legacy is actively managed through a dual strategy: the sacred preservation of the original by its "time immemorial" guardians and the public dissemination of its story through modern replicas.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴