How Freemasonry Forged the Greek Revolution

The Unseen Hand of 1821

On March 25, 1821, at the monastery of Ayia Lavra, Archbishop Germanos of Patras raised a banner of revolution, a defiant act that has become the foundational myth of modern Greece. This public display of rebellion, traditionally marking the start of the Greek War of Independence, was the visible eruption of a volcano whose molten core had been forming in secret for seven years. The force that engineered this cataclysm was a clandestine organization known as the Filiki Etaireia, the "Society of Friends". This sprawling conspiracy was the central nervous system of the revolution, a network that stretched from the merchant houses of Odessa to the mountains of the Peloponnese, uniting merchants, clerics, intellectuals, and warlords under a single, secret oath.

How did a small group of diaspora merchants, operating in the shadows, create a revolutionary network so disciplined and widespread that it could successfully challenge the might of the Ottoman Empire? The answer lies not in a novel invention, but in the meticulous adaptation of a pre-existing blueprint for secret organization, one that had been perfected over the preceding century in the lodges of Europe. The Filiki Etaireia was not merely influenced by Freemasonry; it was a direct and deliberate repurposing of its structure, rituals, and ideology. Its founders, at least one of whom was a confirmed Freemason, consciously reverse-engineered the Masonic framework, transforming a system of moral philosophy and social networking into a potent and ruthlessly effective engine of nationalist revolution.

Forging a Society of Friends

The early 19th century was a time of profound tension and transformation in the Greek world. Centuries of Ottoman rule had not extinguished a burgeoning sense of "Hellenism," a shared national identity fostered by the Greek Orthodox Church, a common language, and the economic dynamism of a rising merchant class. This growing consciousness was electrified by the shockwaves of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, which had disseminated radical ideas of self-determination and national sovereignty across the continent, intensifying the Greek desire for independence.

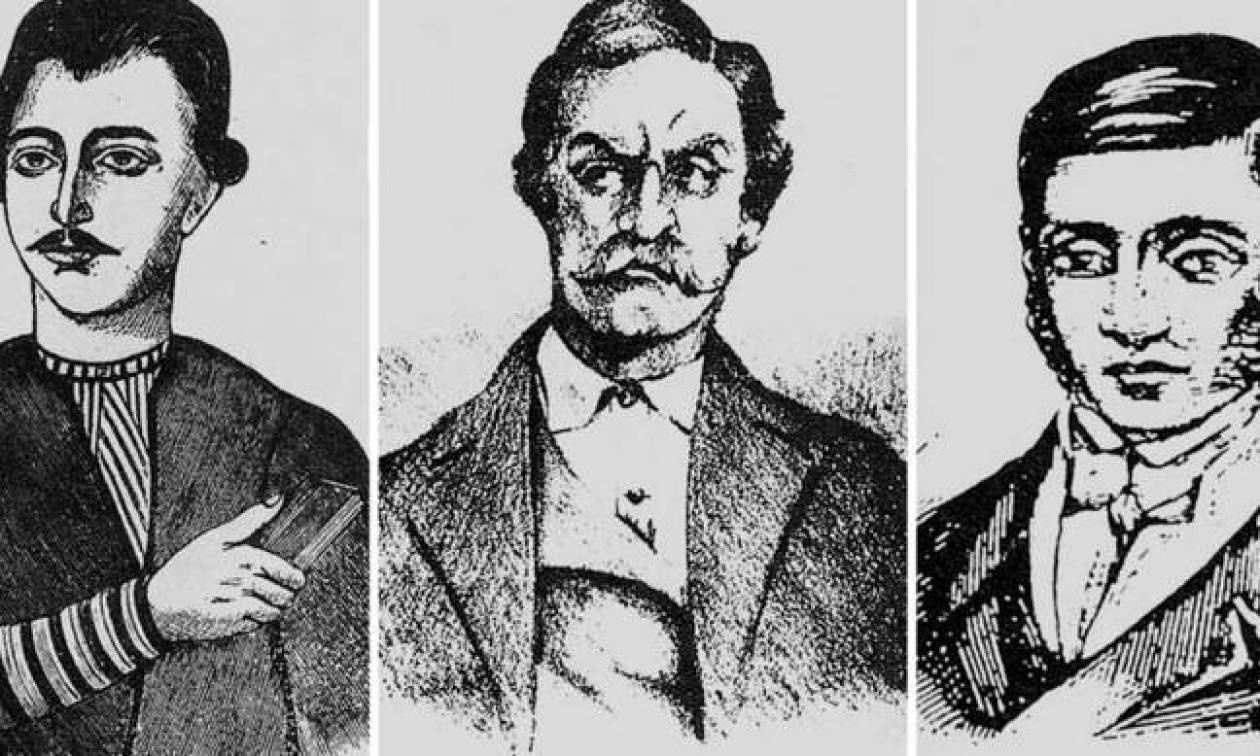

It was in this climate of revolutionary ferment that three men came together in Odessa, a thriving, multicultural port in the Russian Empire that served as a hub for the Greek diaspora. They were not great generals or statesmen, but what one source calls "infamous but visionary petty merchants or clerks". Emmanuil Xanthos was a merchant from Patmos, Nikolaos Skoufas a hatter from Arta, and Athanasios Tsakalov a young student from Ioannina. On September 14, 1814, they founded the Filiki Etaireia with a singular, unambiguous purpose: the "restoration and liberation of the Greek Nation and our Homeland" through a coordinated armed uprising. From its inception, the society aimed for broad appeal; its statutes were written in common Greek, "so that even a shepherd could understand it".

The society's early years were marked by a slow, cautious burn. Between 1814 and 1817, its membership hovered at around twenty, consisting mainly of diaspora Greeks in Russia and the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. This initial phase of careful recruitment, however, gave way to a pivotal shift in strategy. Beginning in 1818, the Etaireia initiated a campaign of mass initiations, and by 1820, its tendrils had spread throughout mainland Greece and into Greek communities across Europe, transforming the small pact into a revolutionary force numbering in the thousands.

A Revolution in "Freemasonic Fashion"

The founders of the Filiki Etaireia made a conscious and explicit decision to model their organization "in freemasonic fashion". This was not a matter of coincidence or vague inspiration; it was a direct and intentional transfer of institutional knowledge and methodology, creating a structure perfectly suited for clandestine revolutionary action.

The Initiates — A Direct Masonic Lineage

The link between the Etaireia and Freemasonry is not a matter of speculation but is rooted in the documented experiences of its founders. The direct, causal connection is irrefutable, established by individuals with firsthand knowledge who deliberately repurposed a proven organizational system.

The key conduit for this transfer was Emmanuil Xanthos. During his travels as a merchant, Xanthos was formally initiated into the "Society of Free Builders of Saint Mavra," a Masonic Lodge on the Ionian island of Lefkada. This experience was not incidental; it was foundational. According to his own memoirs, it was in the lodge that he was inspired by the idea of freedom and "conceived the idea that a secret society could be formed with similar principles as those of the free masons". When he proposed the Etaireia to his co-founders, he explicitly "revealed to them that he was a member of the Masonic Society and he explained some of its principles, those that could be used in the new one". This testimony provides a direct causal link, demonstrating that the Etaireia's structure was not an accident but the result of a deliberate act of organizational borrowing.

Athanasios Tsakalov provided a second, independent stream of institutional knowledge. Before co-founding the Etaireia, he had been a founding member of the "Hellenoglosso Xenodocheio" (Greek-speaking Hotel) in Paris. This earlier society, established under the patronage of the influential Greek-Russian diplomat Ioannis Kapodistrias, was described as a "Masonic Centre" where "Masonic work was closely associated with the secret preparation for the liberation of Greece". Tsakalov thus brought direct experience from another Masonic-style political organization to the table.

While direct evidence of Nikolaos Skoufas's own Masonic initiation is less clear, his deep immersion in the revolutionary underground is well-documented. His associate, Konstantinos Rados, was a member of the Italian Carbonari, a revolutionary society with Masonic roots. Furthermore, it was Tsakalov who initiated Skoufas into the revolutionary methods he had learned in Paris. The Grand Lodge of Greece also lists Skoufas as a member under the category "Friendly," indicating his full integration into this clandestine world.

A Hierarchy of Secrets — Comparative Structure

The Etaireia adopted a strictly hierarchical, pyramid-like structure designed for maximum security and operational control. At its apex was the "Invisible Authority" (Αόρατος Αρχή), a masterstroke of psychological manipulation. By hinting that this supreme council included powerful figures like Tsar Alexander I of Russia, the founders created an aura of immense power and prestige that was crucial for recruiting members. The reality was far more mundane: initially, the "Authority" consisted of only the three founders.

Below this mysterious leadership, the society was organized into four distinct levels of initiation, a system of progressive revelation borrowed directly from Masonic practice. The levels were:

- Brothers (Αδελφοποίητοι) or Vlamides (Βλάμηδες)

- The Recommended (Συστημένοι)

- The Priests (Ιερείς)

- The Shepherds (Ποιμένες)

This structure was a critical security measure. Lower-level members—the Brothers and the Recommended—were kept entirely ignorant of the society's ultimate revolutionary aims. They were told only that they were part of a society working for the "general good of the nation". Only those who proved their loyalty and were elevated to the rank of Priest or Shepherd were entrusted with the full, explosive secret of the planned insurrection. This compartmentalization of knowledge mirrored the Masonic system of degrees, where secrets and symbols are explained in stages, ensuring that the core mysteries of the organization are protected.

The structural parallels between the two organizations are systematic and profound, pointing to a clear case of deliberate imitation.

| Feature | Craft Freemasonry | Filiki Etaireia |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Body | Grand Lodge / Worshipful Master of a Lodge | "Invisible Authority" (Αόρατος Αρχή) / "The Twelve Apostles" |

| Basic Unit | The Lodge | The "Temple" (Ναός) |

| Entry Level | Entered Apprentice | Brother (Αδελφοποίητος) / Vlamis (Βλάμης) |

| Intermediate Levels | Fellow of the Craft | The Recommended (Συστημένος) |

| Senior Levels | Master Mason | Priest (Ιερεύς) |

| Highest Core Level | (Varies, but Master Mason is key) | Shepherd (Ποιμήν) |

| Knowledge Principle | Progressive revelation of allegorical and moral secrets. | Strict secrecy; revolutionary goal revealed only to higher levels. |

| Recruitment Agent | Existing Member (Sponsor) | "Priest" (Ιερεύς) |

Oaths, Signs, and Symbols — The Ritualistic Transfer

The adoption of Masonic methods went beyond mere structure to encompass the very rituals that bound the organization together. The founders of the Etaireia understood a crucial point: these rituals were not just elaborate theater but a proven technology for building a resilient and secure revolutionary network. In a conspiracy where the primary threats are betrayal from within and discovery from without, the dramatic ceremonies, solemn oaths, and shared secrets of Freemasonry provided the ideal tools for forging powerful emotional bonds and ensuring absolute loyalty. Initiation into the Etaireia was a solemn ceremony administered by a "Priest," culminating in the "Great Oath". This was no symbolic gesture; it was a binding contract, with the understanding that betrayal was punishable by death. To allow members to identify one another securely across the vast expanse of the Ottoman Empire and the European diaspora, the Etaireia adopted the Masonic system of secret passwords, signs, and grips (secret handshakes). This secret language was a functional imperative, the only way to verify a fellow conspirator in a world of spies and informants. The Etaireia even adopted Masonic terminology, calling its society a "Temple" (Ναός), a direct reference to the Masonic lodge as a symbolic representation of Solomon's Temple.

The Ideological Inheritance: From Universal Brotherhood to National Liberation

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, Masonic lodges served as crucial social spaces for the dissemination of Enlightenment ideals. Within their walls, principles of rationalism, civic virtue, and merit-based advancement were promoted. A core tenet was a form of non-sectarian universalism, the idea "to regard the whole human Species as one Family". These ideas found fertile ground in the Neo-Hellenic Enlightenment, where Greek intellectuals and merchants in the diaspora, such as the revolutionary visionary Rigas Feraios, were absorbing and spreading calls for liberty. The lodges they joined in cities like Moscow, Paris, and Vienna became, as one analysis notes, "veritable repositories of knowledge, where the information and ideals needed to start an uprising were collected and shared".

The true genius of the Filiki Etaireia, however, lay in its ability to perform a kind of ideological alchemy. The founders took the abstract, universalist ideals of Freemasonry and radically repurposed them for a concrete, particularist, and nationalist goal. They stripped the Masonic framework of its original apolitical philosophy while retaining its powerful organizational structure and its vocabulary of virtue and duty. They then poured a new, potent ideology—Hellenic nationalism—into this pre-existing mold.

- The Masonic ideal of "Brotherly Love" was transformed into patriotic allegiance to the Greek nation.

- The symbolic "Temple" to be built was not an edifice of personal morality but the literal, independent Greek state.

- The Masonic tenet of obedience to the "law of the land" was subversively reinterpreted to mean absolute obedience not to the ruling Ottoman authorities, but to the commands of the "Invisible Authority" and the future laws of a liberated Greece.

This act of ideological transformation reveals the Etaireia not just as an imitator, but as a brilliant and ruthless innovator. It demonstrates how a social and philosophical framework can be weaponized by changing its core ideological content—a process with profound implications for understanding the mechanics of revolutionary movements.

A European Web of Conspiracy: The Carbonari and the Revolutionary Zeitgeist

The Filiki Etaireia did not emerge in a vacuum. It was part of a broader European phenomenon in the post-Napoleonic era, a period defined by the reactionary politics of the Holy Alliance and the repressive regimes of figures like Austria's Klemens von Metternich. In this climate, open dissent was impossible, forcing all liberal and nationalist movements underground into a web of clandestine networks.

The Etaireia's closest contemporary and ideological cousin was the Carbonari ("charcoal-burners") of Italy. Like the Etaireia, the Carbonari had Masonic origins, a hierarchical structure, and secret rituals, and they aimed to achieve a constitutional government for a unified Italy. Their revolutionary attempts in 1820-21, though ultimately crushed by Austrian intervention, sent shockwaves across Europe, creating a "wave of imitators" and fueling a widespread belief in the power of secret societies. The Etaireia was "strongly influenced by Carbonarism," with the connection of founder Nikolaos Skoufas to the movement providing a direct channel of influence.

Yet, the Filiki Etaireia represented a significant evolutionary advancement in revolutionary design. The Carbonari were ultimately hampered by diffuse and sometimes conflicting political goals; some members wanted a republic, others a limited monarchy, and still others a federation. This ideological ambiguity contributed to their failure. The founders of the Etaireia learned from this. They adopted the proven structure of Freemasonry and the aggressive revolutionary intent of the Carbonari but focused it on a single, galvanizing, and unambiguous objective: ethno-nationalist liberation. This clarity of purpose gave the Etaireia a decisive advantage, allowing it to unite a broad coalition—from Phanariot intellectuals to Peloponnesian warlords—who might have disagreed on the future form of government but were absolutely united in the goal of expelling the Ottomans.

From Clandestine Plot to Open Rebellion

After 1818, with its headquarters relocated to the heart of the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople, the Etaireia began its transformation into a mass movement. A council of twelve "Apostles" was appointed, each dispatched to a different region to initiate new members and establish local cells. The most critical step was the strategic recruitment of key military figures—the klephts and armatoloi (mountain warlords and militia)—such as Theodoros Kolokotronis, Odysseas Androutsos, and Anagnostaras, who gave the conspiracy its military teeth.

The final piece of the puzzle was securing a high-profile leader. After being famously rebuffed by Ioannis Kapodistrias, who deemed the plot dangerously premature, Xanthos finally secured the leadership of Prince Alexander Ypsilantis in April 1820. As a high-ranking officer in the Tsar's army, Ypsilantis lent immense credibility to the myth of Russian support and provided the movement with a nominal commander-in-chief.

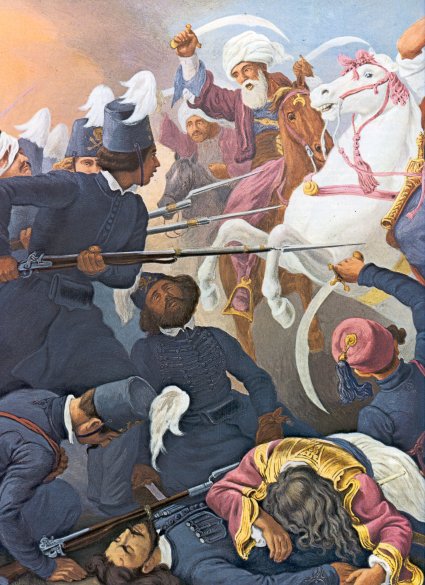

The Etaireia's plan was two-pronged. In February 1821, Ypsilantis crossed the Prut river and launched an invasion of the Danubian Principalities. This campaign was a military disaster. Lacking local support and officially repudiated by the Tsar, it culminated in the heroic but tragic destruction of the "Sacred Band" at the Battle of Dragashani. However, it served its primary strategic purpose: it acted as a crucial diversion, drawing Ottoman forces northward. As the Sultan's armies were occupied in the north, the Etaireia's extensive network in southern Greece was activated. The secret preparations of seven years finally bore fruit as the Peloponnese erupted in revolt on March 25, 1821, igniting the true, sustainable heart of the Greek War of Independence.

A Nation Forged in Secret Lodges

The Greek Revolution of 1821 was not a spontaneous uprising but the culmination of a meticulously planned, seven-year conspiracy orchestrated by the Filiki Etaireia. The society's remarkable operational success was owed directly and unequivocally to its Masonic blueprint. Freemasonry provided the robust organizational structure, the proven ritualistic methods for ensuring loyalty and secrecy, and a powerful ideological vocabulary of brotherhood and virtue that was brilliantly repurposed for a nationalist struggle. The story of the Filiki Etaireia stands as a powerful case study in how abstract organizational models, born from the philosophical currents of the Enlightenment, can be adapted and weaponized to achieve concrete political ends. The independent Greek state, born in the fire of revolution, was a nation whose foundational blueprints were first drafted in the secrecy of a society built in the image of a Masonic lodge.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴