The Invisible College and 17th-Century Free-Masonry

The question of whether the mid-17th-century intellectual circle known as the "Invisible College" was a Masonic organization is a query that probes the very heart of the English Enlightenment. It seeks to connect the birth of modern experimental science with the traditions of one of the world's most enduring fraternal societies. To answer it requires navigating a complex historical landscape of civil war, intellectual revolution, and the evolution of clandestine and private societies. The period in question, emerging from the crucible of the English Civil War, was one of profound social and intellectual flux, where old certainties were collapsing and new structures for generating knowledge and fostering civil discourse were urgently needed.

This report will demonstrate that the relationship between the Invisible College and Free-Masonry is not one of direct identity. The two were not the same entity. Rather, the connection is a more nuanced and historically significant one, characterized by an overlap in key personnel, a synergy of purpose, and a shared intellectual heritage that laid the groundwork for the modern world.

To begin, it is essential to define the two principal subjects of this inquiry as they existed in the 1640s and 1650s. The "Invisible College" was not a single, formal organization with a charter and membership roll. It was a term, most famously used by the natural philosopher Robert Boyle, to describe a network of scholars and experimenters dedicated to the "new philosophy". This philosophy championed empirical observation and experimentation over the scholastic reliance on ancient authority. The group's "invisibility" stemmed from its lack of a physical headquarters and its reliance on correspondence and informal meetings, a practical necessity in a time of political turmoil.

Concurrently, "speculative Free-Masonry" was in a critical period of transition. It was evolving from the operative guilds of medieval stonemasons into a philosophical fraternity, admitting "gentlemen Masons" who were not connected to the building trade. Crucially, this was decades before the 1717 formation of the first Grand Lodge in London, meaning 17th-century Free-Masonry was a decentralized collection of independent lodges, not a monolithic, centrally governed body.

The historiography of this topic is fraught with challenges, ranging from rigorous academic analyses to assertive but poorly substantiated claims from Masonic authors and the speculative fantasies of conspiracy theorists. This report will navigate this terrain by prioritizing documentary evidence and scholarly consensus, distinguishing between confirmed facts, plausible inferences, and unfounded conjecture. A fundamental error in many popular treatments of this subject is the application of modern, rigid definitions of an "organization" to the fluid, informal, and evolving networks of the 17th century. To ask if one was the other presupposes a level of formal structure that simply did not exist for either group at the time. The more historically accurate and fruitful inquiry, which this report will undertake, is to examine the intersection, mutual influence, and parallel development of two contemporaneous movements that were both pioneering new forms of social and intellectual organization in a fractured world.

The "New Philosophy"

Robert Boyle and the Correspondence Network

The primary documentary evidence for the name "Invisible College" comes from the personal correspondence of Robert Boyle, a central figure in the scientific revolution. In letters written in 1646 and 1647 to his former tutor Isaac Marcombes, the scholar Francis Tallents, and the London-based "intelligencer" Samuel Hartlib, Boyle refers to "our invisible college" and "our philosophical college". An analysis of these letters reveals that Boyle was not describing a secret society with clandestine oaths, but rather an informal and geographically dispersed network of like-minded individuals. Their association was defined by a shared commitment to a new way of acquiring knowledge and was sustained through the exchange of letters.

This mode of operation was a direct response to the conditions of the era. The ongoing English Civil War made public association dangerous, and the established universities were still largely mired in scholastic traditions that were resistant to the "new philosophy". By forming a "college" without walls, its members could safely correspond, share the results of their experiments, establish precedence for their discoveries, and critique one another's work. Its invisibility was therefore a function of its structure—a decentralized network rather than a chartered institution—which provided both safety and intellectual freedom.

The Two Circles, Hartlib, Gresham, and Wadham

Historical scholarship reveals that the term "Invisible College" has been used, often interchangeably, to describe at least two distinct but overlapping circles of intellectuals active in mid-17th-century England. A careful delineation of these groups is essential to understanding the movement's true nature.

The first was the Hartlib Circle, a vast and ambitious correspondence network managed by the polymath Samuel Hartlib. This group was animated by the utopian ideals of pansophism—the belief that all knowledge could be unified—and was deeply invested in educational and social reform. Its intellectual interests were broad, encompassing not only natural philosophy but also alchemy, Hermeticism, and theology. Some scholars, such as Margery Purver, argue that Boyle's 1647 reference to the "invisible college" most accurately describes this group around Hartlib, which was actively lobbying Parliament to create a centralized "Office of Address" for the exchange of information.

The second, and more direct precursor to the Royal Society, was the Gresham/Wadham Group. This circle began meeting around 1645 at Gresham College in London, convened by individuals like Theodore Haak, and later found a vibrant center at Wadham College, Oxford, under the leadership of its Warden, John Wilkins. This group's focus was more narrowly defined and pragmatic, centered on what they termed "Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning". Their meetings involved witnessing experiments and discussing topics in physics, astronomy, anatomy, and chemistry. While there was overlap in membership and communication between the two circles, the Gresham/Wadham group's specific dedication to experimental science marks it as the institutional seed of the Royal Society. The 18th-century historian Thomas Birch was the first to explicitly identify this Gresham group as the "invisible college," an identification that became orthodox but is now subject to scholarly debate.

The Baconian Mandate

The intellectual foundation for both circles of the Invisible College was the philosophy of Sir Francis Bacon. The core principles of the movement were profoundly Baconian: the conviction that knowledge is power and that its ultimate purpose is utilitarian—for the "relief of man's state" and not merely for its own sake. This represented a revolutionary departure from the prevailing academic culture, which determined truth by deference to the authority of ancient texts, primarily Aristotle, and the doctrines of the Church.

The members of the Invisible College rejected this dogma, valuing knowledge only "as it hath a tendency to use," in the words of Robert Boyle. They championed a new method based on empirical observation, meticulous experimentation, and inductive reasoning, seeking to build theories from a foundation of verifiable facts. To facilitate this focused pursuit of knowledge and to ensure the group's survival in a period of intense political and religious strife, the Gresham group adopted a crucial rule: a strict ban on the discussion of "Divinity, of State- affairs and of News other than what concerned our business of Philosophy". This pragmatic apoliticism was a key feature of their methodology and social organization.

The Invisible College can thus be understood as more than just a collection of brilliant individuals; it was an innovative social technology designed for the generation and validation of knowledge. Frustrated by the dogmatism of existing institutions, its members created a decentralized, collaborative, and meritocratic system. Through the medium of correspondence and informal meetings, they developed a prototype for what would become the modern scientific process of peer review, replication of experiments, and the rapid dissemination of results. This network was a flexible and resilient structure for intellectual progress that could thrive even amidst the chaos of civil war. The evolution of this system culminated in the founding of the Royal Society, which formalized these practices and, in a landmark development, created the world's first peer-reviewed scientific journal, the Philosophical Transactions.

English Free-Masonry in the Age of Transition

From Operative to Speculative

To assess any potential connection with the Invisible College, one must first understand the state of Free-Masonry in mid-17th-century England. The fraternity was undergoing a profound transformation. Historically, Masonic lodges were "operative," meaning they were guilds for working stonemasons who possessed the technical secrets of cathedral building. However, beginning in the early 1600s and accelerating throughout the century, these lodges began to admit "accepted" or "speculative" members—men of social standing and intellectual curiosity who were not connected to the stonemason's trade.

This influx of "gentlemen Masons" gradually shifted the focus of the lodges from the practical business of construction to the allegorical and philosophical exploration of the builder's tools and legends. By the middle of the century, some lodges in England and Scotland consisted almost entirely of speculative members, indicating that the fraternity's primary purpose was evolving from a trade union into a society dedicated to moral philosophy and social fellowship.

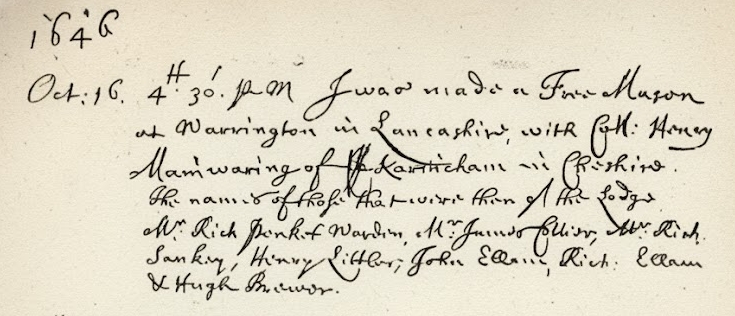

The Ashmolean Benchmark and the 1646 Initiation

The most significant piece of documentary evidence confirming the existence of purely speculative Free-Masonry during this period is the diary of the antiquary Elias Ashmole. On October 16, 1646, Ashmole recorded his initiation into a lodge held at Warrington in Lancashire. He meticulously listed those present, and subsequent research has shown that none of them had any known connection to operative masonry.

The Ashmole diary entry is a historical benchmark. It provides unambiguous proof that organized, speculative Masonic lodges were active in England at the very same time that the natural philosophers of the Invisible College were beginning to convene in London and Oxford. This chronological concurrence is the foundational premise for any argument of a potential link between the two movements. Ashmole's initiation demonstrates that Free-Masonry had already evolved into a form that would be attractive to the intellectual elite, providing a private forum for association and discussion.

The Pre-1717 (1721) Landscape, A Fraternity Without a Head

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the fact that 17th-century Free-Masonry was a decentralized phenomenon. The Premier Grand Lodge of England, which would become the first central governing body for the Craft, was not established until 1717 (or 1721 per recent research). Before this date, Masonic lodges were independent, self-governing entities. There was no national leader, no standardized ritual, and no central authority to grant charters or enforce regulations.

This structure means that to be a "Free-Mason" in the 1650s was to be a member of a specific, local lodge. While these lodges shared a common heritage, mythology, and system of recognition, they were not branches of a single, monolithic organization. This reality refutes any simplistic notion of the Invisible College being "the Free-Masons." Rather, it opens the possibility that certain individuals could have been members of both a scientific circle and a local Masonic lodge, bringing the values and practices of one sphere into the other.

The Philosophical Aims of Early Speculative Masonry

The rise of speculative Masonry was a direct response to the societal trauma of the 17th century. England was torn apart by the Civil War, a conflict fueled by irreconcilable political and religious differences. In this climate of extreme intolerance, the Masonic lodge emerged as a unique social sanctuary. It was one of the few places where men from opposing sides of the conflict—Royalists and Parliamentarians, Anglicans and Puritans—could meet on common ground.

The core principle of speculative Free-Masonry was to create a private, neutral space where the divisive topics of politics and religion were forbidden. Instead, members were to unite on universal principles of brotherhood, morality, charity, and a shared pursuit of knowledge, symbolized by the builder's art. The goal was to build a better, more harmonious society by first building better men. This fundamental tenet of creating an apolitical space for collaborative improvement provides a striking parallel to the guiding philosophy of the Invisible College. Both movements, it appears, arrived at a similar solution to the same existential problem: how to foster progress—be it scientific or social—in an age of destructive factionalism. They each developed a "social technology," the private, rule-bound, apolitical society, as a means of survival and advancement in a world where public discourse had failed. This shared functional purpose made the two movements naturally attractive to the same kinds of forward-thinking individuals, who sought to build a new, more rational world out of the ruins of the old one.

A Confluence of Minds

The most compelling evidence for a connection between the Invisible College and Free-Masonry lies in the biographies of the key figures themselves. A systematic analysis reveals a pattern not of identity, but of significant and influential overlap.

Elias Ashmole

Elias Ashmole stands as the single most unequivocal bridge between the two worlds. His diary confirms his 1646 initiation into a speculative Masonic lodge, and he remained an active Free-Mason for at least 35 years, attending a meeting in London as late as 1682. Simultaneously, Ashmole was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society and a man whose intellectual pursuits were emblematic of the era's eclecticism. His deep interest in alchemy, astrology, and antiquarianism, alongside his support for the new experimental science, demonstrates that the 17th-century mind did not perceive a firm barrier between scientific inquiry and esoteric traditions. Ashmole's dual affiliations are a documented fact, proving that at least one prominent founder of England's premier scientific institution was also a committed Free-Mason.

Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren was an undisputed giant of the scientific movement. A brilliant astronomer, geometer, and physicist, he was a central figure in the Gresham/Wadham group, and it was after his lecture at Gresham College on November 28, 1660, that the twelve men present resolved to found what would become the Royal Society.

The evidence for Wren's Masonic membership is substantial and comes from multiple sources, though it falls short of the definitive proof offered by Ashmole's diary. This evidence includes:

- A handwritten note in a 1691 manuscript copy of his friend John Aubrey's Naturall Historie of Wiltshire, which states, "This day... is a great convention at St. Pauls' church of the fraternity of the Adopted Masons: where Sir Christopher Wren is to be adopted a Brother".

- James Anderson's The Constitutions of the Free-Masons (1738 edition), which explicitly names Wren as a Grand Master of the fraternity.

- Multiple London newspapers, such as the Postboy and the British Journal, which described Wren as "that worthy Free-Mason" in his death notices in 1723.

- A long and persistent tradition held by the Lodge of Antiquity No. 2, one of the four founding lodges of the Grand Lodge, which claims Wren as a former Master.

While the absence of definitive lodge records prevents absolute certainty, the cumulative weight of this contemporaneous and near-contemporaneous testimony from his friends, the press, and Masonic authorities makes his membership highly plausible.

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle was a leading natural philosopher, a pioneer of modern chemistry, and the man who gave the "Invisible College" its name. His unwavering commitment to experimentalism and his rejection of unsubstantiated hypotheses defined the group's scientific ethos. However, despite his central role, there is no credible documentary evidence to suggest he was ever a Free-Mason. Indeed, scholarly consensus finds it "unlikely". Boyle was famously scrupulous about taking oaths, a conviction so strong that it led him to decline the Presidency of the Royal Society in 1680. This same scruple would almost certainly have precluded him from undergoing the obligatory oaths of a Masonic initiation. Boyle's status serves as a critical counter-argument to any theory that posits a simple identity between the Invisible College and Free-Masonry.

Sir Robert Moray

After Ashmole, Sir Robert Moray provides the most definite and significant link. A Scottish soldier, diplomat, and spy, Moray was initiated into a Masonic lodge at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1641 by members of the Lodge of Edinburgh. This is the earliest known record of a speculative Masonic initiation taking place in England. Moray was a founding member of the group that became the Royal Society and served as its first president. His role was absolutely pivotal. As a trusted courtier of the newly restored King Charles II, it was Moray who secured royal approval and, ultimately, the Royal Charter that formally established the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. This demonstrates a direct, high-level, and confirmed Masonic presence at the very moment of the scientific institution's formal birth.

John Wilkins and Samuel Hartlib

John Wilkins and Samuel Hartlib were the organizational and intellectual engines of the two main circles. Wilkins, as Warden of Wadham College, was the charismatic leader who fostered the collaborative and tolerant atmosphere essential for the Oxford group's success. Hartlib was the central node of a vast international correspondence network, a tireless promoter of knowledge and reform. Despite their foundational roles in the broader movement, there is no credible evidence linking either Wilkins or Hartlib to a Masonic lodge. Hartlib's intellectual connections, in fact, point more strongly toward continental reform movements and esoteric traditions like Rosicrucianism. Their absence from the Masonic record further reinforces the conclusion that the Invisible College was a broader intellectual current that included Masons but was not defined or exclusively driven by them.

The complex web of these affiliations is best summarized in a table, which provides a clear visual representation of the pattern of overlap and distinction.

| Name | Role in Invisible College / Royal Society | Evidence of Masonic Membership | Assessment of Masonic Link | Other Relevant Affiliations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elias Ashmole | Founding Fellow, Royal Society | Diary entries (1646, 1682) | Confirmed | Alchemist, Antiquary, Astrologer |

| Sir C. Wren | Founding Member, Royal Society; Architect | Aubrey's MS (1691), Constitutions (1738), Obituaries (1723) | Disputed but Plausible | Architect, Astronomer, Geometer |

| Robert Boyle | Leading Member, "Invisible College"; Chemist | None; circumstantial claims rejected by scholars | Unlikely / Unproven | Natural Philosopher, Theologian |

| Sir Robert Moray | Founding President, Royal Society | Documented initiation (1641) | Confirmed | Soldier, Diplomat, Spy |

| John Wilkins | Leader of Wadham College Group; Organizer | None | Unproven | Warden of Wadham, Bishop |

| Samuel Hartlib | Leader of the "Hartlib Circle"; Intelligencer | None; linked to Rosicrucianism | Unproven | Pansophist, Hermeticist |

The Rosicrucian Shadow

The "Invisible College of the Rosy Cross"

Any deep inquiry into the Invisible College must acknowledge the influence of Rosicrucianism, a spiritual and cultural movement that caused a sensation across Europe in the early 17th century. The connection begins with the name itself. The Rosicrucian manifestos, particularly the Fama Fraternitatis (1614), announced the existence of a secret brotherhood of enlightened sages working to reform the arts, sciences, and society. These texts referred to their fraternity as an "invisible" one. The historian Frances Yates, in her seminal work The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, identifies this mythical group as the "Invisible College of the Rosy Cross". It is highly probable that Boyle and his contemporaries, who were well-versed in the intellectual currents of the day, borrowed this evocative term directly from the widely circulated Rosicrucian literature. The term carried with it connotations of a select, enlightened group working for the betterment of humanity, a self-perception that suited the natural philosophers perfectly.

A Common Intellectual Ecosystem

In the 17th century, the boundaries that now separate science from esotericism were far more porous. Figures who are today celebrated as pioneers of science, including Robert Boyle and, later, Sir Isaac Newton, saw no fundamental contradiction between conducting rigorous physical experiments and pursuing alchemy, theology, or Hermetic philosophy. The intellectual ecosystem they inhabited was one where the search for the hidden laws of nature and the search for divine or hidden wisdom were often seen as two sides of the same coin. This is particularly evident in the Hartlib Circle, where Samuel Hartlib, described as a "famed Hermeticist," had documented connections to the "shadowy Rosicrucian Brotherhood" and counted alchemists among his correspondents. This demonstrates that the intellectual milieu that birthed the Royal Society was steeped in traditions that modern observers might label as mystical or occult. A Philosophical Bridge?

Rosicrucianism and its associated Hermetic philosophy may have served as a conceptual bridge, providing a set of shared ideas and aspirations that influenced both the natural philosophers and the emerging speculative Free-Masons. While direct evidence of Rosicrucian influence on the ritual and structure of 17th-century Masonic lodges is scarce and difficult to prove before the 18th century, a powerful intellectual synergy existed.

Both movements were built upon core ideas that resonated with the Rosicrucian mythos: the formation of a private or secret brotherhood, the use of allegory and symbolism to convey deeper truths, and a collective pursuit of a hidden or poorly understood form of knowledge, whether it be the secrets of nature or the principles of moral enlightenment.

This historical progression reveals a fascinating transformation from a powerful literary idea into tangible social institutions. The Rosicrucian manifestos presented Europe with an exciting, utopian, but ultimately mythical, vision of a secret brotherhood changing the world. The genius of the English innovators was to take this compelling metaphor and instantiate it into real, functioning structures. Robert Boyle and his network adopted the name and the concept of an "invisible college" to describe their practical, reality-based system of scientific collaboration, effectively turning a myth into a method. In parallel, speculative Free-Masons were building actual lodges—physical and social spaces—that embodied the Rosicrucian ideal of a private brotherhood dedicated to enlightenment and mutual improvement. The founding of the Royal Society represents the culmination of this process. With the crucial assistance of confirmed Free-Masons like Sir Robert Moray, the "invisible" scientific college became a visible, chartered, and royally endorsed public institution, making the utopian dream a concrete reality.

A Venn Diagram of Influence

Overlap, Synergy, and Influence

While not identical, the relationship between the two movements was profound and is best characterized as a significant and influential overlap, which can be visualized as a Venn diagram.

- Overlap in Personnel: The intersection of the two circles was populated by some of the most important figures of the age. The confirmed Free-Masons Elias Ashmole and Sir Robert Moray, and the highly probable Mason Sir Christopher Wren, were not peripheral actors but central figures in the establishment of the Royal Society. Their dual membership created a direct conduit for ideas and social practices between the two spheres.

- Synergy of Purpose: Both movements independently developed as solutions to the crisis of the English Civil War. They provided protected, apolitical "safe spaces" where intellectuals could collaborate without fear of political or religious persecution. The Masonic lodge, with its established rules of order, its emphasis on harmony, and its strict ban on sectarian debate, provided a proven and valuable social model for the natural philosophers seeking to do the same for scientific inquiry.

- Influence on Formation: The most direct point of contact was in the formalization of the Royal Society. The role of Sir Robert Moray, a confirmed and high-ranking Free-Mason, in securing the Royal Charter from King Charles II is undeniable proof of direct Masonic influence at the institution's moment of creation. A Free-Mason was, in effect, the diplomatic midwife at the birth of the world's pre-eminent scientific institution.

The Shared Spirit of the Enlightenment

Ultimately, the deepest connection between the Invisible College and speculative Free-Masonry is their shared intellectual DNA. Both were quintessential products and powerful promoters of the early Enlightenment. They were animated by a common spirit: a belief in progress, a faith in the power of human reason, a commitment to discovering truth through evidence and experience, and a profound optimism that a better world could be built through the collaborative efforts of enlightened individuals. They were parallel streams flowing from the same intellectual wellspring, both seeking to replace a world governed by dogma and division with one based on knowledge, tolerance, and reason. A Note on Historiography: Dismissing the Conspiracy

Finally, it is necessary to address and firmly dismiss the ahistorical and unsubstantiated narratives that have grown up around this topic. Claims that the Invisible College was a centuries-old anarchistic cabal engaged in secret wars against Free-Masonry, or a group of "bloodthirsty diabolists," are the products of modern fiction, role-playing games, and conspiracy culture, not credible historical research.

These narratives stand in stark contradiction to the overwhelming documentary evidence of the Invisible College's true purpose: the systematic, collaborative, and open (among its participants) pursuit of scientific knowledge for the public good. Such theories serve as a cautionary tale in historical inquiry, highlighting the critical importance of relying on primary sources, scholarly analysis, and verifiable evidence when separating the intricate history of these movements from the myths they have inspired.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴