George Washington's Lifelong Engagement with Free-Masonry

The Enduring Question of Washington's Masonic Zeal

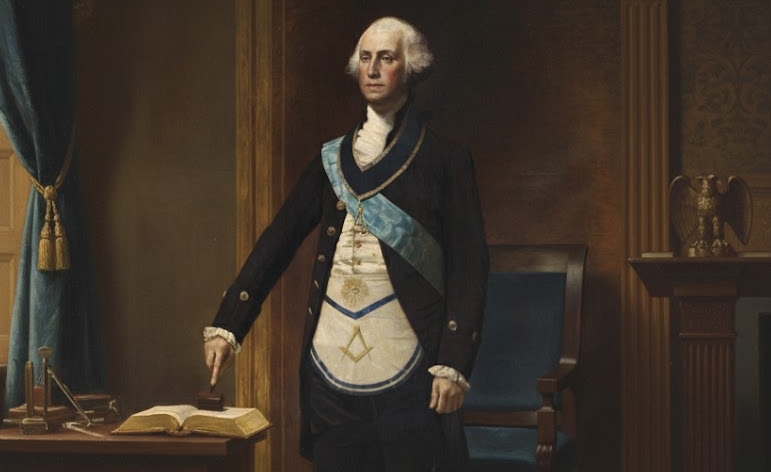

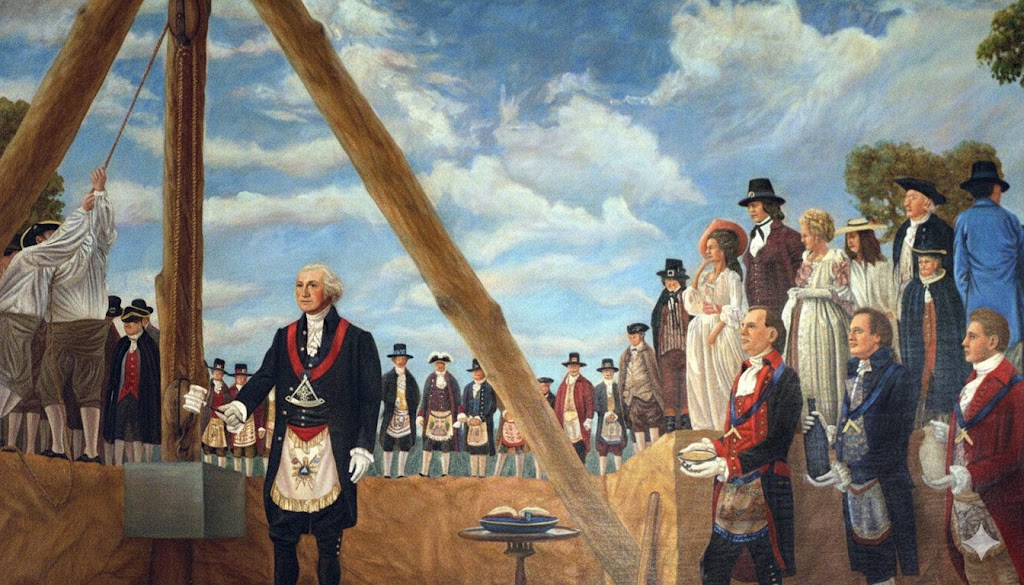

The image of George Washington as a Freemason is an indelible part of the American cultural and historical landscape. It is an image cast in bronze and carved in stone, most monumentally in the towering George Washington Masonic National Memorial that stands sentinel over Alexandria, Virginia. Paintings depict him in full Masonic regalia, presiding over the laying of the U.S. Capitol cornerstone, the trowel of the builder in hand, a symbol of his role as the principal architect of the new republic. This popular conception presents Washington not merely as a member, but as a zealous and deeply committed leader of the Masonic fraternity.

Yet, this powerful iconography stands in stark contrast to a more ambiguous documentary record. A close examination of surviving lodge minutes, particularly from his early years, reveals a man whose attendance at regular meetings was, at best, infrequent. This apparent contradiction has long fueled a historiographical debate: Was Washington's connection to Free-Masonry a profound, guiding influence throughout his life, or was it a youthful social affiliation that he maintained largely for political and symbolic convenience? To answer the question of whether he was "highly engaged" requires moving beyond a simple tally of attendance.

It is important to understand that George Washington's Masonic engagement cannot be measured by the conventional metric of participation in stated lodge meetings. Instead, it must be understood as a complex and evolving relationship that served distinct and vital purposes at different stages of his extraordinary life. In his youth, it was a rite of passage, a vehicle for social advancement in colonial Virginia. During the crucible of the American Revolution, it became an invaluable tool for fostering military cohesion and a shared sense of identity among a fractious officer corps. As president, he transformed his Masonic affiliation into a powerful symbol of republican leadership, employing its rituals to sanctify the foundational moments of the United States. Finally, in his personal life, it provided an ethical framework that mirrored his own Stoic-inflected virtues. His engagement was not one of consistent, weekly participation, but rather one of profound, strategic, and symbolic impact. By analyzing his actions—from accepting the Master's chair in his home lodge to his public correspondence and his final Masonic burial—this paper will demonstrate that Washington's commitment to the fraternity was measured not in the frequency of his attendance, but in the gravity of his involvement at the moments that mattered most.

Initiation and Early Activity in Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4

George Washington's entry into the Masonic fraternity was a deliberate and pragmatic step for an ambitious young man navigating the hierarchical society of colonial Virginia. It was a move that reflected both his personal aspirations and the broader cultural significance of Free-Masonry as an institution of social and professional advancement in the mid-18th century. His early years as a Mason, centered in Fredericksburg, establish a foundational pattern: a formal and sincere commitment to the institution, immediately complicated by the overwhelming demands of his public career.

The Masonic Context of Colonial Virginia

In the 1750s, Free-Masonry was a rapidly expanding social phenomenon throughout the British Empire, and Virginia was no exception. Lodges served as exclusive but accessible networks for men of good character, bringing together planters, merchants, lawyers, and government officials. For a young man like Washington, whose family was well-to-do but not among the colony's uppermost elite, membership was a "rite of passage" into a more genteel and influential stratum of society. The fraternity, which had attracted members of the British aristocracy and even the royal family, was a clear avenue for a young man who aspired to rise in the world, perhaps even to secure a King's commission.

The lodge forming in Fredericksburg was a natural fit. A bustling commercial port with a significant population of Scottish tobacco merchants, many of whom brought their Masonic traditions with them, the lodge was a hub of local influence. For Washington, whose childhood was spent at nearby Ferry Farm, joining this nascent group of influential men was a logical step in his personal and professional development.

Initiation Record

The minute books of the Lodge at Fredericksburg provide a clear and indisputable record of Washington's entry into the Craft. On November 4, 1752, at the age of 20, he was initiated as an Entered Apprentice. The lodge records note the payment of his entrance fee: two pounds and three shillings. His advancement through the degrees followed in due course. Ten days after his 21st birthday, on March 3, 1753, he was passed to the degree of Fellowcraft. Several months later, on August 4, 1753, he was raised to the sublime degree of Master Mason. These ceremonies were conducted using a Bible printed in 1668, an artifact that Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4 (as it was later designated) still preserves as one of its most treasured relics. This documented progression over a nine-month period demonstrates a standard and complete entry into the fraternity, fulfilling all the requirements of the time.

The Attendance Paradox

The central challenge to the narrative of Washington's deep Masonic commitment arises immediately after he was made a Master Mason. The same lodge minute books that so carefully record his initiation are equally clear about his subsequent attendance. The surviving records document his presence at only two further meetings of his "Mother Lodge": the first on September 1, 1753, and the second on January 4, 1755. After this, his name disappears from the attendance rolls of the Fredericksburg lodge. This sparse record—just two visits in the nearly half-century that followed his raising—forms the primary evidence for the argument that his Masonic affiliation was nominal and that his interest quickly waned.

However, interpreting this absence as disinterest requires ignoring the dramatic and immediate context of Washington's life. His limited attendance was not a reflection of his regard for the fraternity but a direct and unavoidable consequence of the sudden and all-consuming launch of his military and public career. An examination of his professional timeline reveals a direct correlation between his duties on the frontier and his absence from the lodge room.

In October 1753, just one month after his first visit back to the lodge as a Master Mason, Major Washington was dispatched by Virginia's Governor Robert Dinwiddie on a perilous diplomatic mission to the Ohio Valley to warn the French to vacate the region. This journey marked the beginning of his deep involvement in the conflict that would become the French and Indian War. His life was no longer that of a local surveyor and gentleman with the leisure for regular social meetings. He was now a key military and political figure in Virginia's westward expansion. His second and final recorded visit, on January 4, 1755, occurred during a brief lull in his military activities, following his difficult expedition that ended with the surrender at Fort Necessity in July 1754 and preceding his service as an aide to General Braddock in 1755.

Therefore, a direct causal link exists between his high-stakes public duties and his physical absence from Fredericksburg. The question is thus reframed from "Was he engaged?" to "How did his Masonic identity manifest when faced with competing, life-altering responsibilities?" The evidence suggests that while his active participation in his home lodge ceased, his affiliation did not. He remained a member in good standing of Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4 for the rest of his life, a fact confirmed by his inclusion in the lodge's necrology after his death. His early Masonic years were not a period of waning interest, but a foundational experience that was quickly and practically superseded by the call of duty to his colony and, eventually, his country.

Free-Masonry as a Fraternal Bond in the Continental Army

The American Revolution marked a profound transformation in George Washington's relationship with Free-Masonry. What had been a passive, if sincere, affiliation in his youth became an active and strategic asset in his role as Commander-in-Chief. Faced with the monumental task of forging a cohesive army from the disparate militias of thirteen colonies, Washington recognized and utilized the pre-existing fraternal network of Free-Masonry to build morale, foster unity, and reinforce the republican virtues at the heart of the revolutionary cause. During the war, his engagement was not measured by attendance at a home lodge, but by his visible leadership within the Masonic community of the army itself.

The Masonic Officer Corps

A remarkable number of Washington's senior officers were his Masonic brethren. Of the 81 general officers who served in the Continental Army, a full 33—or 41%—are documented as being Freemasons. This roster included men from across the colonies, such as Henry Knox of Massachusetts, John Sullivan of New Hampshire, Mordecai Gist of Maryland, and the Marquis de Lafayette of France. Several of his brothers from his own Fredericksburg Lodge, including Generals Hugh Mercer and George Weedon, served alongside him.

This shared Masonic identity created a crucial bond of trust and a common cultural language within an officer corps often plagued by regional rivalries, personal jealousies, and political infighting. Military lodges, which traveled with the army and which Washington actively supported, provided a unique space where officers from Virginia, Massachusetts, or Pennsylvania could meet "on the level," transcending their colonial origins and military rank to reinforce a shared commitment to one another and to the revolutionary cause.

Wartime Masonic Activities

In stark contrast to his pre-war attendance record, Washington's participation in Masonic events during the Revolution is well-documented. He understood the symbolic power of his presence and used it to great effect.

- On December 27, 1778, the Feast of St. John the Evangelist, he marched in a public Masonic procession in Philadelphia. At a service at Christ Church that day, he was hailed as the "Cincinnatus of America," explicitly linking his leadership to the classical republican ideal of the citizen-soldier.

- He repeatedly celebrated the festivals of the Saints John with the American Union Lodge, a military lodge composed of officers. He attended their celebration of St. John the Baptist's Day at West Point on June 24, 1779.

- Six months later, on December 27, 1779, he was one of 68 visiting brethren who celebrated St. John the Evangelist's Day with the same lodge during the army's difficult winter encampment at Morristown, New Jersey.

- His participation continued throughout the war. On December 27, 1782, he celebrated the same festival with King Solomon's Lodge No. 1 in Poughkeepsie, New York.

These were not merely social calls. As Commander-in-Chief, Washington's attendance at these events was a powerful act of leadership. It signaled his endorsement of the fraternity's principles and visibly demonstrated a bond with his officers that went beyond the chain of command. It was a strategic use of a social institution to achieve a military objective: the cohesion and morale of his army.

Proposals for National Leadership

Washington's stature as the preeminent American Mason grew to such an extent during the war that multiple efforts were made to formalize his position as the head of the Craft in the new nation. In 1777, as Virginia's Masons moved to form their own independent Grand Lodge, Washington was the first man proposed to serve as Grand Master. He declined the honor, citing his all-consuming duties as commander of the army.

More significantly, in late 1779 and early 1780, a movement arose among military lodges and the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania to establish a national Grand Lodge of the United States, with Washington as the "General Grand Master". This proposal reflected a broader desire to create unifying national institutions in parallel with the political project of independence. Free-Masonry, as one of the few organizations that existed in all thirteen colonies, was seen as a potential cultural and moral backbone for the new nation, and Washington was its undisputed choice for leader. Though the plan for a national Grand Lodge did not come to fruition at that time, the proposals themselves are a powerful testament to the degree to which Washington's identity and the Masonic fraternity's identity had become intertwined with the spirit of the Revolution. His engagement had shifted from the personal to the profoundly political and strategic, using the fraternity as an instrument of national unification.

Leadership and Responsibility at Alexandria Lodge No. 22

If the Revolution transformed Washington's Masonic affiliation into a tool of military leadership, his post-war life saw him embrace his most significant and formal Masonic role: that of Worshipful Master of his home lodge. His acceptance of the Master's chair of Alexandria Lodge No. 22 was not a passive honorific but a deliberate act of commitment that represents the apex of his engagement with the fraternity. This decision, made during the critical period of the nation's founding, was a powerful symbolic statement, cementing the link between the leadership of the Craft and the leadership of the new republic.

Affiliation with Alexandria Lodge

Upon his return to private life at Mount Vernon, Washington's Masonic activities naturally centered on the nearby port of Alexandria. On June 24, 1784, he attended the Festival of St. John the Baptist with Alexandria Lodge No. 39, which at the time operated under a charter from the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania. On that occasion, his brethren elected him an honorary member of their lodge. This re-established a formal connection to a local lodge after decades of his life being dominated by military and political affairs far from home.

Accepting the Master's Chair

The pivotal moment came four years later. In 1788, the members of Alexandria Lodge No. 39 decided to transfer their allegiance to the newly formed and more geographically convenient Grand Lodge of Virginia. In their petition for a new charter, they made a bold request: they asked George Washington to serve as their first Master under the Virginia charter. Washington, by then the most revered man in America, agreed. On April 28, 1788, the Grand Lodge of Virginia issued a charter for Alexandria Lodge No. 22, with "His Excellency George Washington, Esquire" named as its Charter Master.

This was a decision of immense significance. Washington was not obligated to accept a local, time-consuming position. His time and his name were his most valuable assets, and he was already being called upon to lead the new national government. By agreeing to be Charter Master, he was not merely accepting an honor; he was taking direct responsibility for the governance, rituals, and well-being of the lodge. This act speaks more forcefully about his commitment than years of passive attendance ever could. He served as the active Master for nearly twenty months, from April 1788 until the lodge's next election in December 1789. The role of Worshipful Master in 18th-century Free-Masonry was substantial, involving presiding over all business, conferring degrees, deciding points of order, and representing the lodge before the Grand Lodge. It was a position of genuine authority and responsibility.

The Master President

The historical timing of this commitment creates an unparalleled symbolic convergence. On April 30, 1789, in New York City, George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States. At that very moment, he was also the sitting Worshipful Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22 in Virginia. He is the only president in American history to have held the highest office in the land and the highest office in a Masonic lodge simultaneously.

This remarkable fact suggests that Washington saw a parallel between the principles required to govern a lodge and those needed to govern the new United States. The Masonic lodge, with its written constitution, its democratic election of officers, its emphasis on order and harmony, and its commitment to moral law, served as a microcosm of the republican ideals he was about to implement on a national scale. His leadership of the lodge was not separate from his leadership of the country; it was a concurrent expression of the same core values. By accepting the Master's gavel, Washington was making a profound statement about the civic value of Free-Masonry, endorsing it as a cornerstone institution for the cultivation of citizens fit to sustain a self-governing republic. It was the ultimate expression of his active and deeply considered engagement with the Craft.

Free-Masonry in the Public Square

During his presidency, George Washington consciously and deliberately brought Free-Masonry from the private space of the lodge room into the public square. He employed the fraternity's rich symbolism and solemn rituals as a form of civil religion, a non-sectarian ceremonial language to sanctify the foundational moments of the American republic. These public acts were not the incidental activities of a private citizen; they were calculated performances by a head of state, designed to legitimize the new nation by associating it with Masonic ideals of reason, order, architecture, and divine providence. This was the most visible and arguably most impactful dimension of his Masonic engagement.

The Inaugural Bible

The very first act of the American presidency was imbued with Masonic significance. On April 30, 1789, when George Washington took the oath of office on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City, he did so with his hand upon a Bible brought from the altar of St. John's Lodge No. 1. The oath was administered not just by the Chancellor of New York, Robert R. Livingston, but by the Grand Master of Masons in New York. This deliberate choice inextricably linked the establishment of the American presidency with the Masonic fraternity, lending the ceremony a solemnity and historical weight drawn from the traditions of the Craft.

The U.S. Capitol Cornerstone

The most dramatic example of Washington's public Masonry occurred on September 18, 1793. On that day, President Washington presided over the cornerstone-laying ceremony for the United States Capitol building, conducting it as a full Masonic ritual. Acting as Grand Master pro tem, he led a procession of his brethren from Alexandria Lodge No. 22 and other local lodges to the site. He was attired in his Masonic regalia, most notably wearing the ornate Masonic apron presented to him by his brother and comrade, the Marquis de Lafayette.

With the assistance of the Grand Master of Maryland, Joseph Clark, Washington used a silver trowel and a marble gavel to set the cornerstone, consecrating it with the traditional Masonic elements of corn (symbolizing nourishment and plenty), wine (symbolizing refreshment and joy), and oil (symbolizing peace and unanimity). By personally leading this ceremony, Washington was engaging in a powerful act of political communication. He was symbolically casting the U.S. government as a new temple—a temple of liberty—being constructed on a firm and virtuous foundation. The new nation, lacking the ancient traditions of European states, needed new rituals to create a sense of shared identity and solemn purpose. Free-Masonry, with its emphasis on a non-sectarian "Great Architect of the Universe" and its allegorical use of the tools of building, provided the perfect ceremonial framework.

Public Correspondence and Recognition

Throughout his presidency and retirement, Washington maintained a consistent and public affirmation of his Masonic ties. He received and graciously responded to numerous letters and formal addresses from Grand Lodges and local lodges across the country, using these exchanges to praise the fraternity's principles. His responses were often published in newspapers, further solidifying the public connection between the nation's leader and the Craft.

Furthermore, he consented to a request from his brethren in Alexandria Lodge No. 22 to sit for a portrait in his full Masonic regalia. The painting, completed by William Williams in 1794, is a striking and unambiguous public declaration of his Masonic identity. It depicts him not just as a general or president, but as a Worshipful Master, adorned with the symbols of the fraternity he so clearly valued. These public acts, taken together, demonstrate that Washington's engagement was not a private hobby but a public affiliation he believed was beneficial to the nation. He consistently and strategically aligned the new republic with the progressive, enlightened values that Free-Masonry championed.

Reconciling a Lifetime of Masonic Association

Any thorough analysis of George Washington's Masonic life must directly confront the apparent contradictions in the historical record. How can one reconcile the man who attended only a handful of meetings at his home lodge with the man who accepted the highest leadership position in his Alexandria lodge? How does the general who actively participated in military lodge festivals during the war square with the retired president who, in 1798, wrote that he had not been in a lodge "more than once or twice, within the last thirty years"? The resolution lies in understanding that Washington's actions and words were always context-dependent, and that his statement to G. W. Snyder was not a literal summary of his Masonic life, but a carefully worded political deflection in response to a dangerous accusation.

The Central Contradiction

The core conflict is clear: on one hand, the minute books of Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4 show a Master Mason who attended only two meetings after his raising. On the other hand, the record is replete with evidence of profound engagement at other times and in other forms: his active participation in Masonic events with the Continental Army; his acceptance of the demanding role of Charter Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22; and his leadership in high-profile public Masonic ceremonies as president. This is not the record of a man with a casual or waning interest, which makes his 1798 letter to G. W. Snyder all the more puzzling.

Analyzing the Snyder Correspondence (1798)

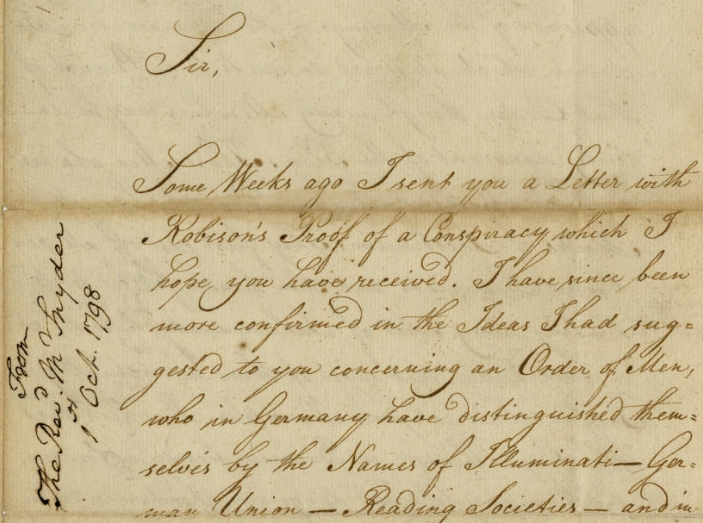

The correspondence with G. W. Snyder, a Maryland minister, provides the most challenging piece of evidence for those who argue for Washington's deep Masonic commitment. Snyder had written to Washington in a state of alarm, enclosing a book titled Proofs of a Conspiracy which alleged that the anti-religious and anti-monarchical secret society known as the Bavarian Illuminati had infiltrated Free-Masonry and was spreading its subversive doctrines in America. In his initial reply on September 25, 1798, Washington sought to correct Snyder's mistaken belief that he presided over American lodges, stating: "The fact is, I preside over none, nor have I been in one more than once or twice, within the last thirty years".

Taken at face value, this statement appears to be a stark repudiation of a lifetime of Masonic activity. It is also demonstrably, if technically, inaccurate. He had attended a banquet at Alexandria Lodge No. 22 in April 1797 and had presided over the massive public ceremony for the U.S. Capitol in 1793. However, to read this sentence literally is to miss its crucial political and rhetorical context.

Washington's statement was not a historical summary; it was a masterful piece of political maneuvering. The late 1790s were a period of intense political paranoia in the United States, fueled by the excesses of the French Revolution. The fear of foreign radicals, Jacobinism, and atheistic conspiracies was rampant. Snyder's letter placed Washington in a difficult position, asking him to comment on an alleged conspiracy within an organization of which he was the most famous member. His response must be read as a political document designed to protect both his own reputation and, more importantly, the reputation of American Free-Masonry from charges of foreign subversion.

By stating he had not been "in one" (a lodge) more than a couple of times, Washington was likely employing a very narrow and literal definition—perhaps referring to attending a regular, tiled, stated communication of a particular lodge. This technicality allowed him to factually distance himself from the day-to-day operations of the fraternity, thereby refuting any possibility that he could be involved in, or even aware of, a subversive plot being hatched within its walls. It was a strategic downplaying of his operational involvement to counter a dangerous political attack.

Crucially, in a follow-up letter to Snyder on October 24, 1798, Washington clarified his position. He stated that he did not doubt that "the doctrines of the Illuminati, and principles of Jacobinism had spread in the United States." In fact, he was "fully satisfied of this fact." His point was more specific: "The idea I meant to convey, was, that I did not believe that the Lodges of Free Masons in this Country had, as Societies, endeavoured to propagate the diabolical tenets of the first, or the pernicious principles of the latter". He did, however, concede that "Individuals of them may have done it."

This clarification resolves the contradiction. The Snyder correspondence does not represent a renunciation of his Masonic ties or a denial of his past engagement. It is a nuanced defense of the institution of American Free-Masonry, distinguishing the character of the lodges themselves from the potential actions of individual members. He recognized the political prudence of minimizing his own operational role to more effectively shield the fraternity from a damaging public controversy. His primary loyalty, as always, was to the stability and security of the American republic.

Washington's Personal Masonic Philosophy

To fully understand the nature of George Washington's Masonic engagement, one must look beyond his actions and attendance to his own words. His extensive correspondence reveals a consistent, pragmatic, and deeply held philosophy of Free-Masonry. He rarely, if ever, discussed the fraternity's esoteric rituals or arcane secrets. Instead, he focused relentlessly on its practical application as a school of ethics, a system of morality that he believed was perfectly aligned with the cultivation of republican virtue and the promotion of public good. For Washington, Free-Masonry was the institutional embodiment of the Enlightenment values essential for the success of the American experiment.

A System of Morality

Washington's letters to various Masonic bodies are remarkable for their consistency of theme. He viewed the fraternity not as a social club or a mystical order, but as a society founded upon principles that directly contributed to the health of the nation. His approbation was grounded in its perceived utility for making good men and, by extension, good citizens.

Two key pieces of correspondence encapsulate his views:

- In a 1798 letter to the Grand Lodge of Maryland, he provided his most concise and widely quoted summary of his Masonic philosophy: "So far as I am acquainted with the principles and doctrines of Free Masonary, I conceive it to be founded in benevolence, and to be exercised only for the good of Mankind; I cannot, therefore, upon this ground, withhold my approbation of it". This statement distills his view to its essence: the fraternity's purpose is benevolence, its aim is the good of humanity, and on that basis, it earns his support.

- In a 1790 address to King David's Lodge in Newport, Rhode Island, he explicitly linked Masonic principles to both private character and public welfare: "Being persuaded that a just application of the principles, on which the Masonic Fraternity is founded, must be promotive of private virtue and public prosperity, I shall always be happy to advance the interests of the Society, and to be considered by them as a deserving brother". Here, he draws a direct line from the teachings of the lodge to the two pillars of a successful republic: a virtuous citizenry and a prosperous state.

This philosophical alignment explains the pattern of his engagement. His commitment was not driven by a desire to attend weekly meetings but by a profound belief in the fraternity's core mission. The lodge was a place where the "living stones" of the republic could be shaped and polished, where men learned the values of integrity, charity, and civic duty. He saw Free-Masonry as a private organization that trained men for public life.

This perspective clarifies why he was willing to lend his immense prestige to the institution at critical moments. When he accepted the Mastership of Alexandria Lodge or laid the cornerstone of the Capitol, he was not merely supporting a club; he was endorsing a system of ethics he believed was vital for the nation's survival. His philosophy of Masonry was inseparable from his philosophy of governance. He supported the Craft because he believed the Craft, in turn, supported the republic.

The Measure of a Mason's Engagement

The historical record, when viewed in its totality, provides a definitive answer to the question of George Washington's Masonic engagement. To judge his commitment by the standards of an ordinary member's attendance record is to fundamentally misinterpret his unique role, his immense responsibilities, and his strategic use of the fraternity. Washington was not "highly engaged" in the conventional sense of being a frequent attendee of stated communications. He was, however, profoundly and strategically engaged at the highest possible level, leveraging his affiliation for military cohesion, civic legitimization, and the promotion of republican virtue.

His Masonic journey evolved in concert with his public life. It began as a young man's rite of passage into Virginia society, an affiliation quickly overshadowed by the call of military duty on the frontier. The Revolution transformed this passive membership into an active tool of command, as he used the shared bonds of the Craft to unify a disparate officer corps. His post-war acceptance of the Mastership of Alexandria Lodge, at the very moment he was being called to the presidency, represents the zenith of his formal commitment—a powerful symbolic act linking the governance of the lodge to the governance of the nation. Finally, as president, his engagement became a public performance, using Masonic ritual as a form of civil religion to sanctify the foundations of the United States. His engagement must be measured not in the quantity of meetings recorded in a minute book, but in the quality and significance of his actions at moments of immense symbolic importance. His decision to lead his lodge while leading the nation, and his act of presiding over the founding of the nation's Capitol in a Masonic ceremony, were acts of engagement far more consequential than a lifetime of ordinary attendance. He was Free-Masonry's greatest champion, not because he was always physically present in the lodge, but because, at the moments that mattered most, he brought the principles of the lodge into the very fabric of the nation.

The final testament to his lifelong bond with the fraternity was his burial. On December 18, 1799, his brethren from Alexandria Lodge No. 22 performed the solemn Masonic rites at his funeral at Mount Vernon, a final honor for the man they considered their most deserving brother. This act closed the circle that had begun 47 years earlier in Fredericksburg, affirming a connection that, while often tested by the demands of history, was never broken.

Appendix: A Chronology of George Washington's Documented Masonic Activities

This timeline consolidates the key documented events of George Washington's Masonic life, providing a chronological framework for the analysis presented in this paper. It illustrates the pattern of his engagement, from his initiation to his wartime activities and his presidential-era ceremonies.

| Date | Location | Event / Activity | Lodge(s) Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nov. 4, 1752 | Fredericksburg, VA | Initiated as an Entered Apprentice | The Lodge at Fredericksburg |

| Mar. 3, 1753 | Fredericksburg, VA | Passed to the degree of Fellowcraft | The Lodge at Fredericksburg |

| Aug. 4, 1753 | Fredericksburg, VA | Raised to the degree of Master Mason | The Lodge at Fredericksburg |

| Sep. 1, 1753 | Fredericksburg, VA | Attended lodge meeting | The Lodge at Fredericksburg |

| Jan. 4, 1755 | Fredericksburg, VA | Attended lodge meeting | The Lodge at Fredericksburg |

| Jun. 23, 1777 | Williamsburg, VA | Proposed as Grand Master of Virginia | Grand Lodge of Virginia |

| Dec. 27, 1778 | Philadelphia, PA | Marched in St. John the Evangelist's Day procession | N/A (Public Procession) |

| Jun. 24, 1779 | West Point, NY | Celebrated St. John the Baptist's Day | American Union (Military) Lodge |

| Dec. 15, 1779 | Morristown, NJ | Proposed as General Grand Master of the U.S. | American Union (Military) Lodge |

| Dec. 27, 1779 | Morristown, NJ | Celebrated St. John the Evangelist's Day | American Union (Military) Lodge |

| Jun. 24, 1782 | West Point, NY | Celebrated St. John the Baptist's Day | American Union (Military) Lodge |

| Dec. 27, 1782 | Poughkeepsie, NY | Celebrated St. John the Evangelist's Day | Solomon's Lodge No. 1 |

| Jun. 24, 1784 | Alexandria, VA | Attended St. John the Baptist's Day celebration; made Honorary Member | Alexandria Lodge No. 39 |

| Feb. 12, 1785 | Alexandria, VA | Walked in funeral procession for Bro. William Ramsay | Alexandria Lodge No. 39 |

| Apr. 28, 1788 | Alexandria, VA | Named Charter Worshipful Master in new Virginia charter | Alexandria Lodge No. 22 |

| Apr. 30, 1789 | New York, NY | Inaugurated as President using the St. John's Lodge Bible | St. John's Lodge No. 1 |

| Sep. 18, 1793 | Washington, D.C. | Presided over the laying of the U.S. Capitol cornerstone | Alexandria Lodge No. 22; Grand Lodge of Maryland |

| Apr. 1, 1797 | Alexandria, VA | Attended a banquet in his honor | Alexandria Lodge No. 22 |

| Dec. 18, 1799 | Mount Vernon, VA | Buried with Masonic honors | Alexandria Lodge No. 22 |

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴