Benjamin Franklin, The Master Mason and Master Diplomat

Benjamin Franklin's Life in Free-Masonry, from the Lodges of Philadelphia to the Grand Orient de France

The Two Aprons of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin presents history with two distinct, yet iconic, personas. The first is the pragmatic American printer, the "Leather-Apron" man. He is the symbol of industrious, homespun American virtue, a self-made polymath who rose from obscurity to found libraries, fire departments, and universities through sheer force of will. He is the face on the $100 bill, the practical scientist, and the moralizing author of Poor Richard's Almanack.

The second persona is the revered sage of the Ancien Régime. This is the Franklin who, in the 1770s, captivated Paris, the man in the simple fur cap who eschewed the powdered wigs of the French court. He was the philosopher-statesman, the celebrated "man who tamed the lightning," and is considered the most successful diplomat in American history.

These two figures—the gritty Philadelphia printer and the sophisticated Parisian statesman—seem worlds apart. Yet, a single, continuous thread binds them together across six decades and an ocean: Benjamin Franklin's deep, strategic, and lifelong active involvement with Free-Masonry. For sixty of his eighty-five years, Franklin was a dedicated Free-Mason.

His engagement with the fraternity was a defining, though often unexamined, feature of his public life. It evolved from a vehicle for personal and civic advancement in colonial America into a sophisticated and powerful instrument of statecraft and cultural diplomacy in Paris. For Franklin, Free-Masonry was not just a "secret club"; it was a laboratory for the Enlightenment, a platform for political maneuvering, and a trusted, international network he masterfully leveraged to build his own career, codify a new American social order, and ultimately, to help secure the future of the United States.

Forging the Craft in Philadelphia

Benjamin Franklin's Masonic career began not in a lodge, but in the pages of his own newspaper. This formative, decades-long career in American Free-Masonry established his reputation within the fraternity and provided the template he would later deploy with such masterful effect in France.

From Satirist to Initiate (c. 1730–1731)

Before he was a member, the young and ambitious printer saw Free-Masonry as a ripe target for satire. In his Pennsylvania Gazette, Franklin published "lighthearted jokes" about the fraternity's supposed secrets, gently mocking their mysterious rituals and exclusivity.

This, however, was not simple mockery. It was a calculated strategy. As a young printer in a new city, Franklin was an outsider. He sought entry into the most influential circles, and St. John's Lodge, the first of its kind in the colony, was a nexus of local power. Some historians believe his joking was a deliberate tactic "to 'advertise' himself to St. John's Lodge". By printing satires, Franklin demonstrated two things: first, that he was aware of the Masons and their importance, and second, that he was a clever writer who controlled a powerful public platform. His articles made him a known quantity, a man whose voice could be valuable, ensuring the lodge would rather have him as a Brother inside the fraternity than a critic outside it.

The strategy worked. Benjamin Franklin was initiated into St. John's Lodge in Philadelphia sometime around 1730 or 1731, likely at the February 1731 meeting.

The transformation was immediate. His tone in the Gazette "changed". He began publishing positive and affirming stories about the Craft, articles that would become a "core for understanding the history of Free-Masons in the United States," especially in Pennsylvania.

The Printer as Grand Master (1732–1749)

Franklin was "in no way a simple and ordinary member". His rise within the fraternity's ranks was, as one source notes, "quick", we was “extremely eager” and produced “marvelous works” mirroring his ascent in business and civic life. His wit, intelligence, and organizational zeal made him a natural leader.

His leadership roles in American Free-Masonry were extensive and foundational:

- In 1732, just a year after joining, he was appointed Junior Grand Warden of the Provincial Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania.

- On June 24, 1734, he was elected Grand Master of Pennsylvania.

- From 1735 to 1738, he served as the Secretary of his home lodge, St. John's, keeping its records.

- In 1749, he was appointed Provincial Grand Master of the colony.

Franklin did not just join the Masons; he was a strong believer in Free-Masonry and its principles, he actively shaped the organization. He drafted by-laws, organized its structure, and, as Grand Master, is even credited by tradition with laying the cornerstone of the new State House, now known as Independence Hall.

Codifying the Craft: The 1734 Constitutions

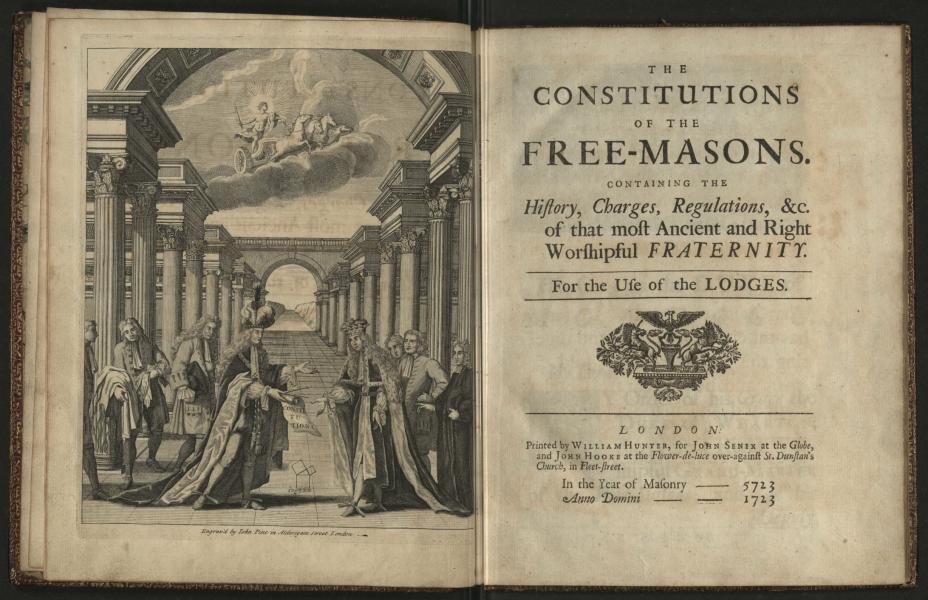

Franklin's most significant contribution to American Free-Masonry was not as a ritualist, but as a printer. In 1734, he "printed the first Masonic book in the United States".

This book was a careful reprint of James Anderson's 1723 London edition, The Constitutions of the Free-Masons. It was a seminal work, containing the history, "ancient legends," charges, and regulations of the Craft.

Interestingly, Franklin did not put his own name on the title page as printer. We know with certainty that it was his work through two methods: "typographical forensics" (scholars have matched the specific typefaces to his press), and, more definitively, a "series of advertisements" he ran in his own Pennsylvania Gazette in May 1734, "all explicitly stating that the book is 'Reprinted by B. Franklin'".

The timing of this publication, however, reveals its true genius. Franklin published the Constitutions "almost exactly at the time that Franklin became Grand Master of Pennsylvania". This was a brilliant synergy of his commercial and social ambitions.

First, as an entrepreneur, Franklin had identified a gap in the market. Copies of the original London edition were "not easily available in the British colonies". He could sell this book.

Second, as an ambitious Mason, he perceived a power vacuum. The fraternity in Pennsylvania was young and needed a unifying, standardizing text to establish its legitimacy and common procedures.

Third, and most critically, as the newly elected Grand Master, he needed this book. By printing and disseminating the Constitutions, Franklin was not just reprinting a text; he was importing and codifying the very rules that legitimized his own authority as Grand Master. He was, in a single act, cementing his new power by providing the "law of the land" while also turning a profit. It was a political, entrepreneurial, and Masonic masterstroke that established him as the "patriarch of American Free-Masonry" decades before he set sail for France.

Franklin's Key Masonic Offices

| Career in Colonial America | |

| c. 1730–1731 | Initiate, St. John's Lodge, Philadelphia, PA |

| 1732 | Junior Grand Warden, Provincial Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania |

| 1734 | Grand Master, Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania |

| 1735–1738 | Secretary, St. John's Lodge |

| 1749 | Provincial Grand Master, Provincial Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania |

| Career in France | |

| c. 1777–1778 | Affiliated Member, Loge Les Neuf Sœurs, Paris |

| 1779–1781 | Vénérable Maître (Worshipful Master), Loge Les Neuf Sœurs, Paris |

| 1782 | Affiliated Member, Respectable Lodge de Saint Jean de Jerusalem |

| 1783 | Venerable d'Honneur (Honorary Worshipful Master), Respectable Lodge de Saint Jean de Jerusalem |

| 1783 | Honorary Member, Lodge des Bons Amis, Rouen |

La Loge des Neuf Sœurs

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in France in December 1776, he was not just a printer or a scientist; he was an American diplomat on a critical, perhaps impossible, mission. The Continental Army was desperate. Franklin's task, assigned by the Second Continental Congress, was "to curry favor" with the French court and secure what the American Revolution needed to survive: money, supplies, and a formal military alliance against Great Britain. He "traveled through many social circles" to achieve this, from salons to the royal court. But his most active and effective theater of influence was a prestigious and unique Parisian Masonic lodge - La Loge des Neuf Sœurs.

An Introduction to the Nine Sisters

The lodge Franklin joined was La Loge des Neuf Sœurs (The Lodge of the Nine Sisters). Founded in 1776 by the esteemed astronomer Jérôme de Lalande, it was a new and extraordinarily influential Lodge under the Grand Orient of France.

Its very name, was a point of contention, when applying for a charter, the Grand Orient de France did not understand why a Lodge withing a Fraternity that only accepts men would call itself “Nine Sisters”, it originally asked for an other name to be picked, but the brethren insisted on it, and explained that is was a reference to the nine Muses of arts and sciences after much debate within the Grand Orient de France, the proposal was approved, this act alone signaled that this was not a typical Masonic lodge. It was, as one French source aptly describes it, "L'Encyclopédie faite loge"—"The Encyclopedia turned into a lodge". It was explicitly designed as a "learned society", and its stated purpose was to "fly to the aid of humanity" by uniting the intellectual, artistic, and political elite of Paris. It was, in effect, the central beacon of the French Enlightenment, a place where, as one source notes, it "symbolizes almost entirely the links between the Enlightenment (Lumières) and Free-Masonry".

The New Lodge however, had a very strict West-gate and refused 90% of its applicant, for one to be admitted, one needed to prove an-already accomplished life in the Arts.

Franklin, already a 40-year veteran of the Craft, was a natural fit. He was elected a member in 1777 or 1778, relishing the "opportunity to study Masonry alongside many of Europe's great minds".

The Power of the Network

For Franklin the diplomat, the Neuf Sœurs lodge was a political goldmine. Membership gave him direct, trusted, and private access to the most influential figures in French society. In a single, private meeting, he could bypass the formal (and often stagnant) channels of royal diplomacy and build consensus with the intellectual and cultural leaders who shaped public opinion and, in many cases, had the King's ear.

The roster of this lodge (see bellow) reveals the sheer power of this network. It was a cross-disciplinary hub where Franklin, the American statesman, could count as his Brothers, the very men who defined the era.

The Network of Les Neuf Sœurs

| Field | Prominent Members | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Science & Academia | Jérôme de Lalande | Founder, famed astronomer, and first Master of the lodge. |

| Antoine Court de Gébelin | Philosopher, author, and Lodge Secretary. | |

| Bernard de Lacépède | Famed naturalist and aristocrat. | |

| Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin | Physician, politician, and social reformer. | |

| Arts & Culture | Jean-Antoine Houdon | The premier sculptor of the era; sculpted busts of Franklin & Voltaire. |

| Jean-Baptiste Greuze | Acclaimed painter and member of the Royal Academy. | |

| Joseph Vernet | Acclaimed painter. | |

| Niccolò Piccinni | Leading Italian composer, a favorite of the Queen. | |

| Politics & Law | Claude-Emmanuel de Pastoret | Jurist, author, and influential Enlightenment politician. |

| Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès | Abbé and key political theorist of the coming French Revolution. | |

| Camille Desmoulins | Journalist and future revolutionary. | |

| Elie de Beaumont | A celebrated lawyer. | |

| The American Cause | Benjamin Franklin | American diplomat and statesman. |

| John Paul Jones | Famed American naval commander. | |

| Philosophy | Voltaire (F.M. Arouet) | The living embodiment of the French Enlightenment. |

The Propaganda Wing

Franklin's position within this network was a "key element in his success" in France. He and his fellow American Brother, the naval hero John Paul Jones, used this platform to "promote the ideals behind the American Revolution".

This was not limited to polite dinner conversation. Franklin actively used the lodge "to acquire financial aid for America, to develop friendships... and to generate propaganda about the seditious American states".

The lodge's activities, in fact, "included a publication dedicated to these purposes, Affaires de l'Angleterre et de l'Amérique". English-language sources have described this periodical as an act of "overtly subversive activity" that "flagrantly violated Masonic regulations" (which typically forbid political plotting), yet was "somehow never really questioned".

A deeper investigation, drawing from French records, reveals why it was never questioned. This was no rogue, amateur "lodge newsletter." A record from the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) provides the critical context: the periodical was "founded and rédigé [written/edited] by Edme-Jacques Genet," the head of the interpreters' bureau at the French Foreign Ministry, and was produced "sous le contrôle du ministre Vergennes" (under the direct control of the French Foreign Minister).

The same record states, "American documentation is provided notably by Benjamin Franklin... who also participate[s] in the writing and translation".

This discovery is profound. The Affaires de l'Angleterre et de l'Amérique was a sophisticated, high-level, clandestine propaganda operation run by the French Foreign Ministry to build public support for the American cause. The Loge des Neuf Sœurs was simply the perfect social and intellectual clearinghouse where the key players—Franklin the diplomat, Genet the bureaucrat, and lodge members like Antoine Court de Gébelin (also a contributor)—could meet, collaborate, and exchange the information needed to fuel this state-sponsored media machine. This directly links Franklin's Masonic life to the core of French foreign policy and his own diplomatic mission.

The Affair of Voltaire, Philosophy, Subversion, and Succession

Franklin's most dramatic and politically perilous moments in France occurred within the Neuf Sœurs lodge, centered around the era's greatest philosopher: Voltaire. These events, a carefully staged piece of theater and a subsequent political crisis, led directly to Franklin's assumption of power within the lodge.

The Initiation of a Titan (April 4, 1778)

In 1778, Voltaire, the 83-year-old patriarch of the Enlightenment, returned to Paris for the first time in 25 years to a hero's welcome. He was, by this time, a living legend. Franklin, himself a 40-year veteran of the Craft, "convinced Voltaire to join" Free-Masonry.

On April 4, 1778, just weeks before his death, Voltaire was initiated as an Entered Apprentice Free-Mason into the Loge des Neuf Sœurs. The event was a sensation. Franklin played a central role, serving as one of Voltaire's "conductors" during the ceremony.

The symbolic high point of the initiation was the presentation of a specific Masonic apron to Voltaire. This was not just any apron; it was the apron of the revered philosopher Claude-Adrien Helvetius, a foundational figure whose widow, Mme. Helvetius, was a close friend of Franklin and helped found the lodge. The apron had been gifted by Helvetius to Voltaire that night; other sources suggest Franklin presented it to Voltaire, who had also worn it briefly.

The lodge, by having Franklin (the living embodiment of the American Enlightenment) conduct Voltaire (the living embodiment of the French Enlightenment) and invest him with the "relic" of Helvetius (the lodge's patron saint), was symbolically uniting the great branches of Enlightenment thought. This, combined with Franklin and Voltaire's famous public embrace at the Academy of Sciences, cemented the Franco-American intellectual alliance in the public mind.

A "Lodge of Sorrow", The Subversive Voltaire Memorial (November 28, 1778)

Voltaire died on May 30, 1778. The Catholic Church, which "unrelentingly abominated" him for his lifelong anti-clerical pronouncements, denied him a Christian burial in Paris.

In response, the Neuf Sœurs lodge did the unthinkable: it held its own public funeral. On November 28, 1778, the lodge conducted a "grandiose commemoration," or "Lodge of Sorrow," to honor its deceased Brother.

This was not a quiet memorial. It was a spectacular "act of defiance flying in the face of the clergy". The ceremony was held in a "vast auditorium dramatically lit and draped in black". It featured eulogies, music by lodge Brothers Gluck and Piccini (who also conducted), and the unveiling of a bust of Voltaire presented by his niece.

Franklin was not merely an attendee; he was a "chief organizer". His "strong participation" was noted by all. He was, after all, seen as the "heir to Voltaire's apron". As one of the surveillants (lodge officers, Warden) assisting the Master, Franklin was a key participant in what amounted to a subversive political act.

Vénérable Maître Franklin (1779–1781)

The backlash was immediate and severe. The lodge had "known nothing but tribulations" since the memorial. King Louis XVI, a "devout Catholic", was incensed by this open challenge to the authority of the Church and, by extension, the Crown.

The "royal displeasure was vented" through the official Masonic channel: the Grand Orient de France, which was headed by the King's own cousin, the duc de Chartres. The Neuf Sœurs lodge was summarily "evicted from their spacious quarters". The lodge that hosted the intellectual elite of Europe "came close to being abrogated" (dissolved) entirely.

The lodge was in a crisis. And Franklin, whose entire diplomatic strategy relied on this "key element" of his social network but also a personal and profound love for this Lodge, could not allow it to be destroyed. The lodge, in turn, needed a protector—a new leader so prestigious he could shield it from the King's anger.

The solution was masterful. On May 21, 1779, Benjamin Franklin was elected the new Vénérable Maître (Worshipful Master) of the Loge des Neuf Sœurs bypassing their own traditions time and patience to save the Lodge.

This was a brilliant political "reset" for all involved. The "choice of Franklin as next Vénérable" was, as the historical record notes, "an important factor in cooling the atmosphere". The French Crown, which had just signed the Treaty of Alliance (1778) with America, simply could not destroy a Parisian lodge that was publicly led by Benjamin Franklin, the toast of Paris and the face of that new, crucial alliance.

By electing Franklin, the lodge insulated itself from the King's anger using Franklin's untouchable prestige. And in turn, Franklin took direct control of his primary intelligence and networking hub, solidifying his power and securing his mission.

He served as Vénérable Maître for two years, from 1779 to 1781. His mastership was "extremely active". He focused on what the lodge did best, increasing its Enlightenment activities by recruiting more intellectuals and holding more assemblies, banquets, and cultural events focused on literature, science, and the fine arts.

The meetings (tenus) of the Nine Sisters were described as; « Un foyer des Lumières, où se tenaient les débats les plus profonds, appelés à façonner le destin du monde et à préserver la liberté pour les générations à venir. » (“A hub of Enlightenment, where the most profound debates were held, debates destined to shape the fate of the world and safeguard freedom for generations to come.)

"Higher Degrees" and "Secret Clubs"

Franklin's association with a "secret society" like Free-Masonry has, over two centuries, attached his name to more speculative and sensational rumors. A critical, evidence-based examination is required to separate historical fact from popular myth.

The Question of "Higher Degrees"

A common query is whether Franklin, such a prominent Mason, received the "Higher Degrees" of the fraternity, such as those of the Scottish Rite or other appendant bodies.

The entirety of the historical record points to Franklin's Masonic life being exclusively rooted in the foundational three "Craft" degrees of the "Blue Lodge": Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master Mason. His immense influence came not from collecting esoteric degrees, but from his leadership in the Craft. He served as Secretary of his lodge, Worshipful Master (Vénérable Maître) of the most important lodge in the world, and Grand Master of Pennsylvania.

While modern Masonic bodies, such as the Scottish Rite, rightfully claim Franklin as a "notable Free-Mason" and a "patriarch", this is a claim on him as a foundational figure of Craft Free-Masonry.

There is a lack of historical evidence in the available records—including the comprehensive Encyclopedia Masonica entry—to suggest that Franklin himself was ever initiated into any "higher degrees". His Masonic identity was fundamentally civic, moral, and political, rooted in the core, Enlightenment-friendly principles of the first three degrees.

Franklin's "Other" Societies

- The Junto (The Leather-Apron Club): In 1727, Franklin founded a club in Philadelphia called the Junto, or the "Leather-Apron Club". This is best understood not as a rival "secret society," but as a precursor to his Masonic life. The research shows he "perceived Masonry, like the Junto... as being an important educational and humanitarian institution". The Junto was a "compact debating club" where young, industrious men met to discuss "moral, political, and scientific topics," promoting concepts like volunteer fire departments and public hospitals. It embodied the same principles of civic-minded mutual improvement that drew him to Free-Masonry four years later. This idea of philosophical and debating club is exactly what he was able to find in Free-Masonry.

- The Hellfire Club Connection: A persistent rumor attempts to link Franklin to the infamous Hellfire Club, a secretive group of British aristocrats known for "pagan" rituals, orgies, and black magic. The facts are far more mundane. The historical record shows only two things: 1) Franklin was a "close friend" of the club's founder, the eccentric and powerful Sir Francis Dashwood. 2) There are "claims" that Franklin, during his time in England, "visited the caves" (the West Wycombe Caves, where the club met) on "more than one occasion". There is zero evidence he was a member or participated in any of their activities. As a diplomat and man of science, Franklin maintained friendships with many powerful and strange figures. The connection is one of documented friendship, not speculative membership.

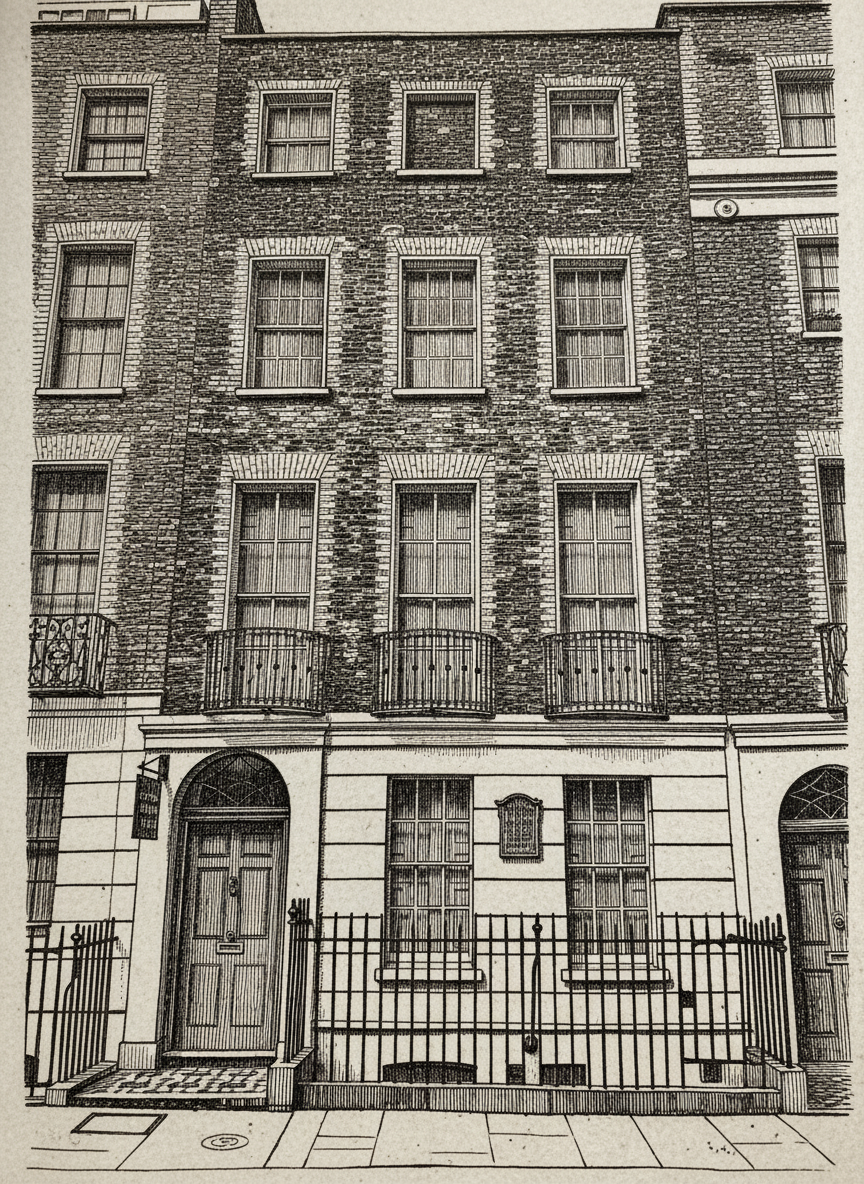

The Skeletons at 36 Craven Street

The most sensational "proof" of Franklin's connection to dark, secret clubs came in 1998. During a restoration of his former London home at 36 Craven Street, "the remains of ten bodies" (four adults and six children) were discovered buried in the basement. The bones were estimated to be "about 200 years old," placing them squarely within the time Franklin lived there (1757-1775).

This discovery led to lurid speculation. The facts, however, point to a scientific, not a ritualistic, explanation. Most of the bones "showed signs of having been dissected, sawn, or cut," and one skull had been "drilled with several holes".

The "principal suspect," according to the Westminster Coroner, was not Franklin, but his friend and tenant, Dr. William Hewson, a Fellow of the Royal Society and a pioneering surgeon. Dr. Hewson "established a rival school and lecture theatre" for anatomy in the house.

In the 18th century, acquiring bodies for dissection was illegal, and "grave robbing" was a capital offense. The most likely explanation is that Dr. Hewson was secretly acquiring bodies, dissecting them for his anatomy school, and then "disposed of in his own house" by burying the remains in the basement to hide the evidence.

Franklin, the landlord and diplomat, "did not necessarily know what was happening below stairs". The "secret club" was an 18th-century anatomy school, and the "victims" were scientific specimens.

The Legacy of a Fraternal Founder

Benjamin Franklin's 60-year Masonic journey began in a humble lodge in Philadelphia and culminated in him leading the most intellectually potent and politically significant lodge in the world. He was, in every sense, a "patriarch" and "one of the most notable Free-Masons in American history".

For Franklin, Free-Masonry was the ultimate expression of the Enlightenment's ideals. It was a rational, deistic, qualitative and "impactful fraternity that, as he wrote, had "no principles or practices that are inconsistent with religion and good manners".

It was an organization dedicated to "continual self-improvement and a search for light" and "humanitarian" aims. He truly "lived and wrote and practiced the principles of the Order".

But he was also a pragmatist. He saw in the fraternity's structure a powerful tool for social and political change. His life proves that the "secret" of 18th-century Free-Masonry was never about occult rituals in dark caves. Its true, functional secret was that it was the era's most effective "social network"—a private, trusted, international brotherhood where a "Leather-Apron" printer could become a Grand Master, an intellectual could become a Vénérable Maître, and a diplomat could find, shelter, and mobilize the very allies he needed to help found a nation.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴