Free-Masonry and the Secret Underground Railroad

The Pillars of Secrecy

In the 19th-century American context, Free-Masonry, formally structured fraternal order navigating complex political neutrality, while the secret underground network was a decentralized, clandestine, and inherently subversive network dedicated to illegal human liberation. Understanding their fundamental differences in structure, purpose, and composition is essential to identifying any credible points of contact.

The Craft the Order, Morality, and Exclusion in Antebellum Free-Masonry

Modern speculative Free-Masonry, which evolved from medieval operative stonemason guilds, was formally established in 1717 (1721) with the founding of the first Grand Lodge in London (the Premiere). It rapidly spread throughout the British Empire, arriving in the American colonies in the early 1730s. By the 19th century, it was the preeminent fraternal organization in the United States, a volunteer association teaching moral, intellectual, and spiritual lessons through a system of three degrees: Entered Apprentice, Fellow-Craft, and Master Mason.

This "Craft" was built on Enlightenment ideals of self-improvement, philosophical discussion, charity, and a required belief in a "Great Architect of the Universe". Its lodges attracted the political, commercial, and intellectual elite, including figures like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, and served as a powerful networking apparatus for the new republic's leadership.

However, the fraternity's universality was contradicted by two critical factors. First, a central tenet of Anglo-American Free-Masonry, as codified by the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE), was the strict prohibition of any discussion of politics or religion within the lodge. In the context of antebellum America, where slavery was the single most dominant and divisive political issue, this rule of "neutrality" was not a neutral act. It effectively rendered the institution, as a whole, silent on the "peculiar institution," making organized, lodge-sanctioned participation in the abolitionist movement an impossibility. Free-Masonry as an institution has not "figured prominently" in the historical debates on slavery and abolition.

Second, Masonic "Landmarks," or ancient regulations, posed a significant barrier. Albert Mackey's 1858 "25 Landmarks," highly influential in America, stipulated that all candidates for initiation must be "free born and of mature age". This rule originated in medieval Europe to distinguish guild craftsmen from serfs. In fact, a serf did not have the right to freely move and meet at will, the same was true with Women, thus they were not allowed to be made Free-Masons. In 18th and 19th-century America, however, this "ancient" landmark took on a new and potent meaning. In a nation where a large portion of the African American population was enslaved, and the legal status of even "free" Black men was precarious, the "free born" requirement served as a highly effective and "legitimate" Masonic tool for de facto racial exclusion. It allowed white lodges to deny Black petitioners not explicitly on the basis of race, but on the basis of legal status at birth—a status that was inextricably linked to race. This seemingly neutral bylaw thus became a cornerstone of institutional segregation within the Craft.

The "Underground Railroad"

The Underground Railroad (UGRR) was not a literal railroad but a "covert and sometimes informal network of routes, safehouses, and resources" utilized by enslaved African Americans to achieve self-emancipation. Estimates suggest that by 1850, as many as 100,000 people had escaped via this network, with some scholars suggesting 500,000 or more by the end of the Civil War.

While often spontaneous, the network grew more organized, particularly after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made escape far more perilous and rendered the Northern states unsafe, pushing Canada as the primary destination.

This network was primarily operated by free and enslaved African Americans, with critical assistance from white abolitionists, notably Quakers. Its operation depended on absolute secrecy, which in turn relied on sophisticated, clandestine communication methods.

Documented and verified forms of communication included:

- Coded Language: The widespread adoption of railroad terminology—referring to escapees as "passengers" or "cargo," guides as "conductors," and safe houses as "stations"—was a documented method used in letters and conversation to mask illicit activities.

- Physical Signals: Conductors and stationmasters used signals to communicate. The most famous belonged to Reverend John Rankin, whose lantern in the window of his house high above the Ohio River guided thousands of fugitives to safety. Phrases like "friend of a friend," borrowed from the Quakers, were also used to identify allies.

- Spirituals: Enslaved people used "signal songs" and "map songs" as a primary method of communication. Harriet Tubman, the UGRR's most famous conductor, used songs to signal to her "passengers" when it was safe to proceed or when danger was near. The lyrics of songs like "Wade in the Water" served as a literal instruction to escapees to travel in rivers to throw bloodhounds off their scent. "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" was often sung to indicate that a conductor was arriving to "carry me home" to freedom.

This documented history must be distinguished from pervasive, unsubstantiated folklore, most notably the "Underground Railroad Quilt Code." This popular theory posits that specific quilt patterns—such as the "Monkey Wrench," "Log Cabin," or "Flying Geese"—were hung on fences or windows as "visual maps" to direct fugitives. However, rigorous historical research has repeatedly debunked this myth. Scholarly sources explicitly state that there is "no historical evidence" or written confirmation from the period to support the theory. The persistence of the quilt code narrative, while romantic, obscures the actual and far more complex organizational, literate, and intellectual work performed by the UGRR's operators. The real secrets of the network were not embedded in domestic artifacts but in coded letters, careful record-keeping, and the disciplined, oath-bound trust of its clandestine human networks.

The Rise of Prince Hall Free-Masonry

The institutional silence of mainstream (white) Free-Masonry on slavery and its use of the "free born" landmark as a racial barrier (in the United States only) created an ideological and organizational vacuum. It was this exclusion that directly led to the founding of an independent, autonomous Black fraternity. This new fraternity would adopt the same Masonic tools, rituals and tenets but repurpose them as instruments of liberation.

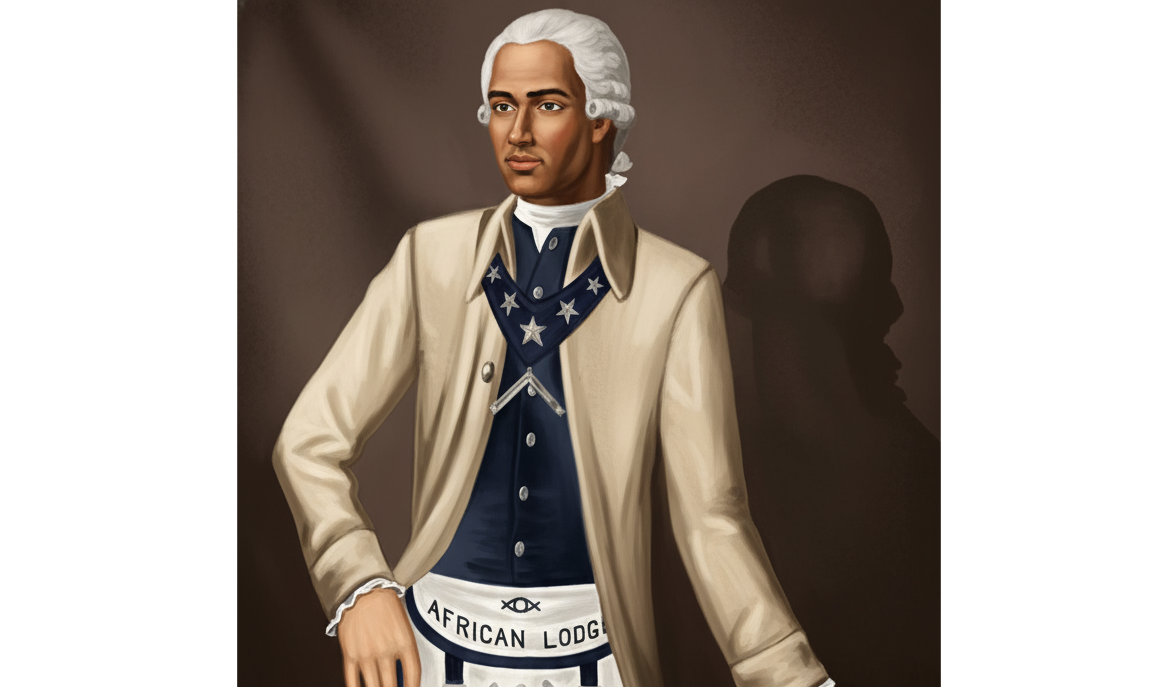

"We Shall Not Be Excluded" the Founding of African Lodge No. 459

The history of Black Free-Masonry begins in 1775 in Boston. Prince Hall—a prominent free Black man, abolitionist, and property owner—and 14 other free Black men sought initiation into the all-white St. John's Lodge. They were rejected.

In a profound historical irony, Hall and his "brethren" turned to the very "tyrant" the colonies were rebelling against. They were initiated by members of an Irish lodge attached to the British forces occupying Boston. This origin story is the ideological key to Prince Hall Free-Masonry (P∴H∴M∴). It was born from a direct confrontation with a blatant hypocrisy, where many of the white "patriot" Masons who championed "liberty" practiced exclusion.

After the Revolutionary War—a war in which Hall himself served in the Continental Army—he petitioned the premier Grand Lodge of England for a formal charter. In 1784, that charter was granted, and African Lodge No. 459 was officially warranted by a legitimate Grand Lodge. This act was monumental. It provided Hall's fraternity with an undeniable Masonic legitimacy, one that was independent of—and, in Masonic terms, equal to—the white American lodges that had rejected them. PHM was, from its very inception, a protest organization, legitimized by the highest Masonic authority of the time.

Free-Masonry as an Abolitionist Tool

Prince Hall Free-Masonry was never intended to be a mere social club; it was immediately activated as an engine to fight for abolition and civil rights as well as safeguarding freedom. Prince Hall himself set the tone, using his status as Grand Master to petition the Massachusetts legislature for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade. He used his own home to operate a school for Black children who were denied access to public education, and his lodge served as a "base for abolitionist activity".

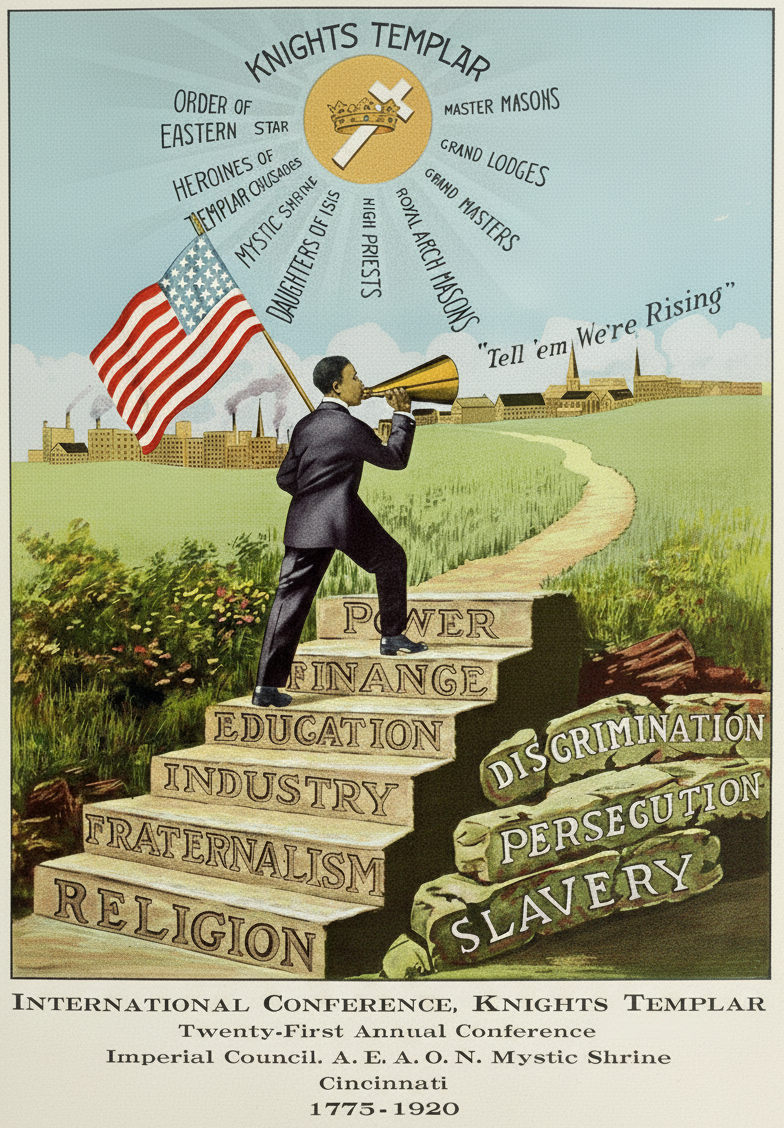

Prince Hall lodges became "proud and assertive black physical and human spaces", one of the only "autonomous black institutions" in the nation. Within these lodges, Black men could organize, lead, and develop what historian Corey Walker terms an "African American 'cartography of democracy'". They adopted the same Masonic principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity (An old masonic motto that later became the motto of France) that white Masons espoused, but they used these Enlightenment ideals "to work against slavery and other forms of racial discrimination".

This is where the Masonic tradition of "secrecy" became a critical tool of subversion. For mainstream white lodges, secrecy was mainly protecting rituals and fostering a private fellowship for in-Lodge discussions. For Prince Hall Masons, secrecy was a shield and a survival mechanism. In a society where any organized Black gathering was viewed with suspicion and often met with violence, the "secret" nature of the lodge provided a protective mantle for activities that were deeply political and, in the case of aiding fugitives, highly illegal. The "sacred space" of the lodge was a secure location where the "quasi-Masonic role in the antislavery tradition" could be planned and executed. The oaths of fidelity were not just ceremonial; they were a practical, life-or-death bond of trust essential for organizing resistance.

Prince Hall Masons and the Underground Railroad

The genuine link between Free-Masonry and the Underground Railroad is not one of vague, universal Masonic brotherhood. The link is specific, documented, and exclusive to Prince Hall Free-Masonry. This connection was not based on secret symbols, but on a shared, clandestine, institutional infrastructure built by a network of dedicated Black leaders.

The Parallel Alliance: The Lodge and the AME Church

The link between PHM and the UGRR is indivisible from the link between PHM and the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. This was not a casual overlap; it was a dual, interlocking institutional structure.

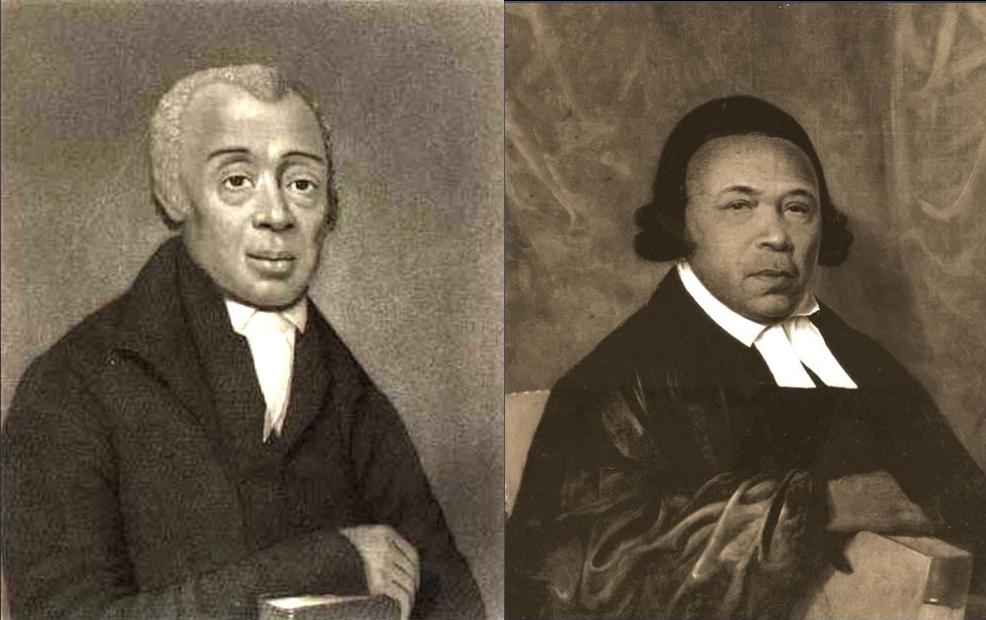

The evidence for this is found in their shared founders. In Philadelphia, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones were two of the most prominent Black men of their era. They were both founding members of Prince Hall Free-Masonry in that city. Simultaneously, they founded America's first independent Black denominations: Allen established the AME Church, and Jones (the first Worshipful Master of his lodge) founded the St. Thomas African Episcopal Church.

This "parallel alliance" became the organizational model for Black liberation across the North. Pastors and prominent congregants of AME churches, which were spreading rapidly, were "often Prince Hall Masons". This dual structure created the perfect infrastructure for the UGRR:

- The Church as the "Station": The AME Church, such as Allen's own Mother Bethel AME, served as a documented UGRR "station" or "safe house". It provided the physical, publicly justifiable sanctuary where "passengers" could be fed, hidden, and sheltered under the guise of religious charity.

- The Lodge as the "Network": The Prince Hall lodge provided the clandestine human network. Its oath-bound, all-male, and secret structure was the ideal vehicle for the "conductors" and "vigilance committees." It was where leaders could communicate securely, vet strangers, raise funds, and coordinate the dangerous logistics of moving fugitives.

The same men, like Allen and Jones, ran both organizations, ensuring seamless and secret coordination.

Conductors, Stationmasters, and Vigilantes, the Documented Masonic Abolitionists

This institutional link is confirmed by the documented biographies of the UGRR's most prominent operators, many of whom were active, and often high-ranking, Prince Hall Masons.

- In Boston: Lewis Hayden, a former slave, became a leader of the Boston Vigilance Committee and a Grand Master of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. His home was one of Boston's most famous UGRR stations. He was also a leader in the 1851 rescue of fugitive Shadrach Minkins, helping to spirit him away in the "getaway" carriage.

- In Philadelphia: William Still, often called the "Father of the Underground Railroad," was the chief clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. He personally coordinated and sheltered thousands of fugitives, keeping meticulous records that would become his 1872 book, The Underground Railroad. Historical analysis identifies Still as a "Prince Hall Mason and Underground Railroad conductor".

- In New York: James Varick, another documented Prince Hall Mason, was the founding Bishop of the Mother Zion AME Church in Harlem. This church, the oldest Black church in New York, was also a documented stop on the UGRR.

- Spreading West: This model was replicated as PHM warranted new lodges in the Northwest Territory. In Illinois, Henry Brown was simultaneously an AME Church minister, a documented UGRR conductor, and a charter member (later Worshipful Master) of Central Lodge No. 19. Prince Hall Mason Abraham Shadd, a UGRR conductor, utilized the PHM network to resettle in Canada following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The scale of this interlocking leadership, which is often overlooked, is best illustrated in tabular form.

Interlocking Leadership in the Black Liberation Network

| Name | Prince Hall Masonic Role | Church Affiliation / Role | Documented UGRR / Abolitionist Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Hall | Founder, African Lodge No. 459; Grand Master | Member, Congregational Church | Abolitionist petitioner; ran school for Black children; Lodge was base for activity |

| Richard Allen | Prince Hall Mason | Founder, African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church | Abolitionist; his church (Mother Bethel) was a documented UGRR station |

| Absalom Jones | Prince Hall Mason; 1st Worshipful Master, Lodge 459 | Founder, St. Thomas African Episcopal Church | Abolitionist; religious leader |

| Lewis Hayden | Grand Master, PH Grand Lodge of MA | Not specified | UGRR stationmaster; Boston Vigilance Committee; led fugitive slave rescue |

| William Still | Prince Hall Mason | Not specified | "Father of the UGRR"; PA Anti-Slavery Society clerk; sheltered thousands |

| Henry Brown | Charter Member & Worshipful Master, Central Lodge No. 19 | AME Church Minister | UGRR Conductor |

| Abraham Shadd | Prince Hall Mason | Not specified | UGRR Conductor |

| James Varick | Prince Hall Mason | Founder & Bishop, Mother Zion AME Church | Abolitionist; his church was a UGRR stop |

The Masonic Lodge as "Station"

Given the roles of their members, it is no surprise that PHM lodges themselves "became important stations along the Underground Railroad" and were "utilized as a safe house". While reports of a "Masonic lodge in Portland" planning escapes confirm this activity, it is crucial to separate this documented structural use from folklore.

Popular imagination, and even some oral traditions, hint at a symbolic link, such as claims that Masons left "carvings on the walls" to signal a safe place. As with the quilt code, there is no academic or documentary evidence to support this. This popular search for a physical symbol misses the true nature of the Masonic "secret."

The "secret" was not a symbol carved on a wall. The secret was the oath-bound, coast-to-coast network of trust. The real "Masonic code" on the UGRR was the ability of a conductor to use the lodge's network to vouch for a stranger, secure passage, and move funds to a "brother" in the next city—a brother who was, by his Masonic oath, dedicated to the cause of liberation. The ceremonial oaths of secrecy that were a matter of tradition for white Masons became a functional, life-or-death bond for Prince Hall Masons engaged in the illegal and holy work of the Underground Railroad.

A Legacy of "Secret" Liberation

The relationship between Free-Masonry and the Underground Railroad is undeniable. The link is not with "Free-Masonry" as a monolithic entity, but specifically and profoundly with Prince Hall Free-Masonry.

From Popular Myth to Historical Fact

The popular query, often rooted in a search for mysterious symbols or a universal brotherhood, is misplaced.

- Mainstream (white american) Free-Masonry was, by its own "apolitical" rules and its "free born" requirement, institutionally silent and a barrier to the abolitionist cause. While some white masons probably have helped wit the cause, there is no evidence of a main movement of mainstream white american lodges participating in the UGRR.

- The true, documented link is with Prince Hall Free-Masonry. This connection was not based on folkloric symbols like quilts or wall carvings. It was a tangible, structural, and personnel-based alliance. It was an oath-bound, clandestine network of lodges and leaders (Hayden, Still, Allen, Jones) that operated in a "parallel alliance" with the AME Church to provide the finances, logistics, safe houses, and secret communication essential for the Underground Railroad's success.

The Overlooked Cornerstone

This history has been largely overlooked. As historian Mary Ann Clawson notes, most historians have traditionally dismissed fraternal orders as "uninteresting or insignificant," with "even less reason to study black Free-Masonry". Based on the growing body of resent research that dismissal can be unequivocally refuted. Far from an insignificant social club, Prince Hall Free-Masonry was a foundational institution of Black civil society at true pillar in the fight for Freedom. Its lodges were the incubators for Black leadership, its re-purposed Masonic tenets were the ideological justification for liberation, and its secret, parallel alliance with the Black Church provided the essential clandestine infrastructure for the Underground Railroad.

Prince Hall Free-Masonry stands as one of America's oldest, most effective, and most overlooked civil rights organizations. The story of the Underground Railroad, and of the broader Black liberation struggle, is incomplete without acknowledging the central, secret, and structural role played by this autonomous Black fraternity. Today Prince Hall Free-Masonry is recognized by most mainstream Grand Lodges in the United States that have agreed to share their jurisdictions with them and it continues to be a pillar of in the African-american communities and is known to be very selective on its membership and provide a large amount of charity and still fights for freedom on a broader scope.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴