The Masonic Tea Party

Whispers at the Green Dragon Tavern

On the cold evening of December 16, 1773, as a band of men disguised as Mohawk Indians moved toward Griffin’s Wharf, the true genesis of their audacious plan lay not at the water's edge, but within the walls of a tavern on Union Street. The Green Dragon Tavern was more than a public house; it was a nexus of revolutionary fervor, serving simultaneously as a clandestine meeting place for the Sons of Liberty and as the property of the Masonic Lodge of St. Andrew. This dual identity—a public house of rebellion owned by a secret society of brothers—frames a historical question that has persisted for nearly 250 years: Was the Boston Tea Party, in essence, a "Masonic Tea Party"?

This question is not a fringe conspiracy theory but a legitimate historical inquiry, rooted in compelling circumstantial evidence that has never been definitively proven or disproven. The primary catalyst for this enduring mystery is a cryptic entry in the official minutes of the Lodge of St. Andrew, which noted an absence of members on the very night of the Tea Party, an entry widely interpreted as a deliberate alibi. Mainstream historical accounts correctly focus on the Sons of Liberty as the event's organizers, often mentioning key patriot leaders like Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere. Conversely, certain Masonic histories and polemical writers have championed a direct Masonic connection, sometimes with more zeal than evidence. This report seeks to navigate the scholarly gap between these positions, examining the evidence with critical rigor.

While the Boston Tea Party was not an official act of Free-Masonry as an institution, the organizational structure, culture of secrecy, and shared political ideology of one specific patriot-leaning lodge—the Lodge of St. Andrew—were indispensable to the event's planning and execution. Through a critical analysis of primary documents, membership rolls, and historical context, this report will distinguish correlation from causation, demonstrating that while the lodge did not act, its members did, using the trust, discipline, and secrecy of their fraternal bonds to orchestrate one of the most iconic acts of American defiance.

Boston on the Eve of the Tea Party

The "Destruction of the Tea" was not a spontaneous riot but the calculated climax of a month-long political crisis that had brought Boston to a standstill. The political tinderbox was primed by a series of British policies that colonists viewed as an existential threat to their rights as Englishmen.

The Political Tinderbox

The immediate cause was the Tea Act of 1773. This was not a new tax but a strategic bailout for the financially troubled British East India Company. The act granted the company a monopoly on the tea trade in the American colonies and allowed it to sell tea directly, bypassing colonial merchants and underselling even smuggled Dutch tea. While the tea would be cheaper for consumers, patriot leaders saw the act as a Trojan horse—a cynical parliamentary maneuver to induce colonists to pay the long-standing Townshend duty on tea, thereby tacitly accepting Parliament's right to tax them without representation.

When the first of the tea ships, the Dartmouth, arrived in Boston Harbor on November 28, 1773, it initiated a 20-day standoff. Colonial law stipulated that if the ship's duties were not paid within 20 days, the cargo would be seized by customs officials—meaning the tea would land regardless. Patriot leaders, organized under the banner of the Sons of Liberty, demanded the ships return to England with their cargo untouched. Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson, however, was equally resolute, refusing to grant the ships the necessary pass to leave the harbor without first unloading and paying the duty. The arrival of two more ships, the Eleanor and the Beaver, only heightened the tension.

In response, a series of massive public meetings, numbering in the thousands, were held at Faneuil Hall and, when that proved too small, at the Old South Meeting House. These gatherings served a dual purpose. On one hand, they were a genuine forum for democratic protest. On the other, they were a form of political theater meticulously staged to exhaust all "legal" options and thus legitimize the illegal act that was being planned in secret. The patriots repeatedly dispatched the ship owner, Francis Rotch, to Governor Hutchinson to request a pass, knowing full well the request would be denied. This public performance of seeking a peaceful resolution demonstrated to the populace that the Governor, not the people, was the intractable party, creating the moral justification for what was to come.

On the final day, December 16, with the deadline for the Dartmouth looming, thousands gathered at the Old South Meeting House. When Rotch returned late in the afternoon with Hutchinson's final refusal, Samuel Adams reportedly declared, "This meeting can do nothing more to save the country". This was the pre-arranged signal. A party of 30 to 130 men, disguised as Mohawk Indians, proceeded to Griffin's Wharf, boarded the three ships, and over the course of three hours, systematically smashed open and dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor. The act was remarkably disciplined; no other property was damaged, and no individuals were harmed. When a padlock was accidentally broken, the patriots reportedly returned the next day to replace it, underscoring that this was a targeted political statement, not an unruly mob.

The Sons of Liberty and Boston Free-Masonry

To understand the potential for a "Masonic Tea Party," one must first dissect the two primary revolutionary networks operating in Boston: the public-facing Sons of Liberty and the secretive lodges of Free-Masonry. These were not mutually exclusive groups; rather, their overlapping memberships and complementary structures formed a powerful engine for rebellion.

An Engine of Protest

The Sons of Liberty emerged from the Stamp Act crisis of 1765, evolving from precursor groups like the "Loyal Nine". Their ideology was simple and powerful: "No Taxation without Representation". Mainstream history correctly identifies them as the primary organizers of the Tea Party. However, their organizational structure was fluid. It was not a formal body with a fixed membership but a "loosely organized, clandestine" network. The name itself was more of an "underground term" for any patriots resisting British policy, allowing organizers to issue anonymous calls to action at symbolic locations like the Liberty Tree. Led by figures such as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere, their methods ranged from propaganda and boycotts to intimidation, tarring and feathering, and the targeted property destruction that characterized the Tea Party, their "seminal act".

The Divided Craft, "Ancients" vs. "Moderns" in Boston

The Masonic landscape in 1773 Boston was not monolithic. It was deeply fractured by a schism that mirrored the city's broader political and class divisions.

- The "Moderns": St. John's Grand Lodge, chartered by the Grand Lodge of England in 1733, represented the Masonic establishment. Its members were generally wealthier merchants and officials with closer ties to the Crown; many would become Loyalists. Their Grand Master was John Rowe, a prominent merchant who owned one of the tea ships, the Eleanor.

- The "Ancients": The Lodge of St. Andrew, chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1756, was a rival body considered "irregular" by the Moderns. Its membership was drawn from Boston's burgeoning class of artisans, tradesmen, and professionals. This group included silversmith Paul Revere, physician Dr. Joseph Warren, and a significant number of sea captains and other men whose livelihoods were directly threatened by British trade policies. This lodge was a known hotbed of patriot activity.

This schism is critical. The theory of a "Masonic Tea Party" cannot apply to Boston Free-Masonry as a whole, as St. John's Lodge was led by a man who stood to lose financially from the event. The inquiry must therefore focus specifically on the patriot-dominated Lodge of St. Andrew.

The relationship between the Sons of Liberty and the Lodge of St. Andrew was symbiotic. The Sons of Liberty provided the broad, public-facing political movement and the manpower for mass action. The Lodge of St. Andrew, in contrast, offered a pre-existing, formal, and secret structure for the core leadership. While the Sons of Liberty was a "loosely organized" banner to rally under, a Masonic lodge was a disciplined body with a formal hierarchy, vetted members, and a powerful oath of secrecy. The key leaders of the patriot cause—Warren, Revere, Hancock—were also the leaders of the Lodge of St. Andrew. They did not need to create a secret society to plan the Tea Party; they already belonged to one. The Lodge provided the secure, trusted, and disciplined environment for the sensitive planning that the more amorphous Sons of Liberty network could not. The Lodge was the command-and-control center; the Sons of Liberty was the operational banner under which the plan was executed.

Assembling the Evidence

While no document explicitly orders Free-Masons to destroy the tea, a powerful body of circumstantial evidence has fueled the "Masonic Tea Party" theory for centuries. This evidence centers on the Lodge of St. Andrew's own records, its physical meeting place, and the identities of the men who participated in the event.

The Secretary's Ledger

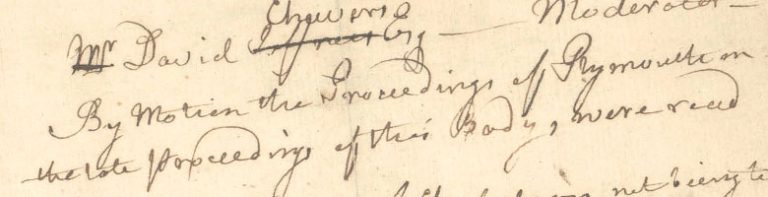

The cornerstone of the theory lies in the Lodge of St. Andrew's minutes book. The entry for the evening of December 16, 1773, is famously brief and suspicious. It states that the lodge meeting was "Closed (on account of the few members present)". This entry is widely interpreted, even by skeptical historians, as a deliberate and rather transparent alibi for the lodge members who were otherwise occupied at Griffin's Wharf.

This interpretation is strengthened by a similar entry from two weeks prior. On November 30, 1773, as the "tea crisis" was escalating, the lodge adjourned its meeting for the annual election of officers "on account of few Brethren present," with the secretary adding a crucial parenthetical note: "(N.B. Consignees of Tea took up the Brethren's Time.)". This earlier entry explicitly links the lodge's official business to the ongoing political protest, establishing a pattern of behavior that makes the December 16th entry appear less like a coincidence and more like a continuation of that pattern.

Adding to the mystique is a claim found in some Masonic histories that the page for the December 16th meeting was filled with large, hand-drawn letters "T". While the symbolic meaning of this is debated, the Tau cross (T) is a significant Masonic symbol, sometimes representing the Grand Architect of the Universe or, when inverted, forming the level, an emblem of a Past Master. Whether it was a coded message signifying "Tea" or a symbolic mark for the initiated, its alleged presence adds another layer of intrigue to the documentary evidence.

The Green Dragon Tavern

The physical location where the patriots met is another critical piece of evidence. The Green Dragon Tavern was not merely a convenient public house; it was purchased by and became the property of the Lodge of St. Andrew in 1764. While the Masons met in the hall on the first floor, the basement was used as a regular meeting place by the Sons of Liberty, the Boston Committee of Correspondence, and the North End Caucus. The tavern became so synonymous with revolutionary plotting that it was dubbed the "Headquarters of the Revolution" by Daniel Webster and was known to Loyalists as a "nest of sedition".

This shared space is more than a coincidence. A contemporary watercolor sketch of the tavern by John Johnson, himself a Mason, depicts the building with Masonic symbols and includes the unambiguous handwritten legend: “Where we met to Plan the Consignment of few shiploads of Tea Dec 16 1773”. This sketch provides a direct, albeit post-facto, visual link between the Masonic-owned building and the planning of the Tea Party on the very day it occurred.

A Fraternity of Patriots

The most compelling evidence comes from cross-referencing the names of known Tea Party participants with the membership rolls of Boston's Masonic lodges. While a complete, definitive list of all Tea Party participants is impossible to compile due to the secrecy of the event, historical research has identified over 100 individuals. Analysis of these lists alongside Masonic records reveals a significant overlap, almost exclusively with the patriot-leaning Lodge of St. Andrew.

The leadership of the patriot cause was deeply embedded in the lodge. Dr. Joseph Warren, a key organizer, was the sitting Grand Master of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge (Ancients). Paul Revere was a Past Master of St. Andrew's Lodge and held the rank of Senior Grand Deacon in the Grand Lodge. John Hancock was also a member. While Warren and Hancock are generally believed to have been planners rather than direct participants, their leadership roles in both the political and fraternal spheres are undeniable.

The table below presents a partial list of men identified as both Tea Party participants and Free-Masons, demonstrating the depth of the connection.

| Participant Name | Known Tea Party Participant? | Known Free-Mason? | Lodge Affiliation (if known) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paul Revere | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew (Past Master) |

| Dr. Joseph Warren | Architect/Planner | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew (Past Master), Grand Master (Ancients) |

| John Hancock | Architect/Planner | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew |

| Thomas Chase | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew |

| Samuel Gore | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew |

| Edward Proctor | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew (Master in 1774-75) |

| Thomas Urann | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew (Master in 1772) |

| Samuel Peck | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew |

| David Bradlee | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St.Andrew |

| Thomas Bradlee | Yes | Yes | Lodge of St. Andrew |

| Nathaniel Barber | Yes | Yes | Mason (Lodge Unspecified) |

| Thomas Hunstable | Yes | Yes | Mason (Lodge Unspecified) |

This quantifiable overlap shows that the men who destroyed the tea were not just random patriots; a significant and influential contingent were bound together by Masonic oaths of secrecy and brotherhood, and they were led by the highest-ranking officers of their lodge.

A Counter-Analysis

Despite the compelling circumstantial evidence, the theory of an officially sanctioned "Masonic Tea Party" collapses under critical scrutiny of its sources and a broader examination of the historical record. The connection between the men of St. Andrew's Lodge and the Tea Party is undeniable, but attributing the act to the institution of Free-Masonry requires a leap of faith that the evidence does not support.

The Problem of Bernard Faÿ

A significant portion of the most explicit claims about a "Masonic Tea Party" can be traced to the work of 20th-century French historian Bernard Faÿ. Faÿ asserted that the event was a "great Masonic day" and that it emanated from the Green Dragon Tavern. However, Faÿ was far from an objective scholar. He was a virulent anti-Masonic polemicist who promoted the idea of a "worldwide Jewish-Free-Mason conspiracy".

His credibility is further demolished by his actions during World War II. As an official in the collaborationist Vichy regime in France, Faÿ directed the government's anti-Masonic service. His office compiled lists of tens of thousands of French Free-Masons, leading to the persecution, imprisonment, and death of hundreds in concentration camps. After the war, Faÿ was convicted of collaboration and sentenced to life in prison.

Masonic historians have accused him of deliberately distorting historical records to fit his anti-Masonic agenda, labeling his work a "set of lies". To build a historical case on the testimony of such a tainted source is untenable.

The Diary of John Rowe

A powerful primary source that directly contradicts the idea of a unified Masonic plot is the diary of John Rowe. Rowe was not only the owner of the tea ship Eleanor, but also the Grand Master of St. John's Grand Lodge, the "Moderns" faction of Boston Free-Masonry that was the rival of St. Andrew's Lodge.

His diary entry for December 16, 1773, written in the immediate aftermath of the event, is telling. He describes the destruction of the tea and concludes: "...this might I beleive have been prevented I am sincerely sorry for the Event".

Rowe's tone is one of genuine regret, not of a man whose fraternity has just executed a bold political stroke. As the highest-ranking Mason in the establishment lodge, his dismay demonstrates that the Tea Party was, at best, a factional action by a single, radical lodge, and certainly not a coordinated effort by Boston Free-Masonry as a whole. His reaction is that of an outsider lamenting a "disastrous affair," not an insider covering his tracks.

Distinguishing Correlation from Causation

The core academic argument against the literal "Masonic Tea Party" theory rests on the logical fallacy of confusing correlation with causation. The fact that many participants were members of the Lodge of St. Andrew is a significant correlation. However, it does not prove that they acted as Masons or that the lodge as an institution sanctioned the event.

A more plausible explanation is that the Lodge of St. Andrew, due to its membership of artisans and professionals with patriot sympathies, functioned as a social network where politically aligned men could build trust and solidarity. In the 1770s, Free-Masonry was one of the most prominent social and civic organizations in colonial cities. It was natural for men who were already political allies to also be fraternal brothers. They undertook the destruction of the tea in their capacity as Sons of Liberty, using the trust and secrecy forged within their lodge to plan the action. The institution of Free-Masonry itself, however, remained officially neutral, containing both Patriots and Loyalists, and a formal, lodge-sanctioned act of treason would have irrevocably shattered the fraternity in Boston. The theory of a "Masonic Tea Party" persists because its proponents fail to make this crucial distinction between the actions of a social network and the official policy of an organization. The Lodge of St. Andrew did not act as a lodge, but its members used the tools of brotherhood and secrecy learned in the lodge to carry out a political act under another name.

A Brotherhood Within a Rebellion

The historical inquiry into the "Masonic Tea Party" reveals a complex relationship between a secret fraternal society and a public act of rebellion. A critical evaluation of the evidence leads to a rejection of the literal theory: the Boston Tea Party was not, in any formal or institutional sense, a Masonic plot. The direct evidence for such a plot is nonexistent, and the theory relies heavily on circumstantial connections and the claims of a discredited, polemical historian. The politically divided nature of Free-Masonry in Boston, exemplified by the dismay of "Moderns" Grand Master John Rowe, makes the idea of a unified Masonic action untenable.

However, to dismiss the connection entirely is to ignore the profound and undeniable role that the Lodge of St. Andrew played as an incubator for the event. The correlation between membership in this specific lodge and participation in the Tea Party is too strong to be a coincidence. The lodge provided three essential elements that the more amorphous Sons of Liberty lacked: a secure and private physical space for planning (the Green Dragon Tavern); a deeply ingrained culture of secrecy and discipline, enforced by solemn oaths; and a pre-vetted, trusted network of "brothers" whose loyalty to one another had been tested and affirmed in ritual.

The Boston Tea Party was an act of the Sons of Liberty, but the core group of planners and participants were also the brothers of the Lodge of St. Andrew. They leveraged the social technology of their fraternal order—its secrecy, its structure, and its bonds of trust—to orchestrate a political act. The event was not Masonic, but it was profoundly shaped by Masons. The whispers at the Green Dragon Tavern on that December night were not of Masonic ritual, but of revolution, spoken by men whose commitment to liberty was reinforced by their commitment to each other as brothers.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴