The Philosophical Scottish Rite

Le Rite Ecossais Philosophique

Le Rite Ecossais Philosophique (R∴E∴P∴), or the Philosophical Scottish Rite, represents one of the most unique and historically niche systems of 18th-century French Freemasonry. Its very existence is a testament to an era of profound esoteric experimentation, standing as a distinct body of initiatory thought. However, its identity is frequently obscured, historically and in modern analysis, by the terminological similarity to the globally dominant Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté (REAA), or Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, as well as other systems bearing the "Scottish" moniker, such as the Rite Ecossais Rectifié (RER), or Rectified Scottish Rite.

The REP is fundamentally different from these contemporaries. It is not merely a variation in ritual; it is a system built upon a completely different philosophical foundation. Whereas the REAA evolved into a broad, syncretic system of moral, chivalric, and Kabbalistic philosophy, and the RER was codified as a system of Christian mysticism and theurgy, the REP was established as a vehicle for Hermetic philosophy and, most specifically, the study and symbolic practice of alchemy.

This esoteric and "philosophical" (in the 18th-century sense of "natural philosophy" and "scientific" esotericism) focus on "inner wisdom" and "mystery traditions" set it apart from the more moralistic or social-political streams of Freemasonry. This unconventional nature was so pronounced that the 19th-century Masonic historian Gould, in the first edition of his History of Freemasonry, famously dismissed the Rite as "a Masonic perversion". This judgment, later corrected, was not merely a historical error but an ideological one. It reflected the discomfort of mainstream, moral-allegorical Freemasonry with a Rite that embraced the "scientific" and quasi-operative goals of Hermeticism—such as the "purification of imperfect metals" and the pursuit of a "universal medicine" —as central tenets rather than as mere symbols. The REP, therefore, exemplifies a major intellectual schism in 18th-century Masonry: the tension between Rites dedicated to social-moral virtue and those, like itself, dedicated to the pursuit of gnosis and the "sublime science of the knowledge of nature".

Marseille, Avignon, and the Hermetic Fount

The historical genesis of the Philosophical Scottish Rite is a complex narrative that was, for many years, misunderstood. Recent scholarship, particularly following the discovery and analysis of archives in the Calvet museum in Avignon by René Désaguliers, has corrected the historical record.

The Rite's naissance, or birth, occurred in Marseille, where the Mère-Loge du rite (Mother Lodge of the Rite) was established at the Loge de Saint Jean (Lodge of St. John). However, the crucial vector for the Rite's development and diffusion was not its birthplace. The pivotal event in its history occurred on August 31, 1774, when the Mother Lodge in Marseille granted a patent to the lodge Saint Jean "La Vertu Persécutée" (St. John of "Persecuted Virtue") in Avignon.

From this moment, Avignon became the true philosophical and spiritual center of the new system. It was from Avignon, not Marseille, that the Rite successfully spread, first to Paris—where it was formally constituted in 1776—and subsequently into the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands). The Parisian development and the original Marseillaise filiation were, for a time, "more or less forgotten" in favor of the Avignon lineage.

The choice of Avignon as the Rite's developmental hub is highly significant. Until 1790, Avignon was a papal seat, an enclave of the Papal States within the territory of France. This unique political status created a "liminal space" for esoteric experimentation. The Rite's founders operated outside the direct jurisdiction of both the French Crown and, perhaps more importantly, the centralizing authority of the Grand Orient de France, which was actively attempting to bring all French lodges under its control.

In this autonomous zone, a system focused on alchemy and Hermeticism—practices viewed with deep suspicion by both the Catholic Church and mainstream Freemasonry—could flourish. The very name of the Avignon lodge, "Persecuted Virtue," is likely a direct and polemical reference to this context. It positions the Rite's teachings (the "Virtue") as the true, uncorrupted essence of Masonry, "persecuted" by the dual exoteric forces of the established Church (which led to the "wrath of the Holy Inquisition") and the politicized, non-esoteric "mainstream" of French Freemasonry.

Dom Pernety and the Illuminés d'Avignon

The unique philosophical and spiritual "DNA" of the Philosophical Scottish Rite is inextricably linked to its key intellectual architect: Dom Antoine-Joseph Pernety (1716-1796). Pernety was a fascinating figure of the 18th-century esoteric revival. A former Benedictine monk, he developed a profound interest in Hermeticism and alchemy, particularly after reading Abbé Longlet-Dufresnoy's L'Histoire de la philosophie hermétique in 1741.

After leaving his monastic order, Pernety traveled, eventually settling in Avignon, where he was initiated as a Freemason. There, he founded his own esoteric society, the Illuminés d'Avignon (Illuminati of Avignon). It is crucial to distinguish this group from its more famous and politically-oriented contemporary, Adam Weishaupt's Bavarian Illuminati, with which it had "practically nothing in common".

Pernety's system was a syncretic fusion of his deep alchemical pursuits, Hermetic philosophy, and the mystical-angelic teachings of the Swedish visionary Emanuel Swedenborg, whose works Pernety had encountered and translated into French while serving as librarian to Frederick the Great in Berlin.

This personal philosophy became the basis for a new Masonic system. Pernety authored his own Rite Hermétique (Hermetic Rite), which was explicitly "based on alchemical principles" and was adopted by the Avignon lodge Les Séctateurs de la Vertu (The Sectators of Virtue).

The historical trail is direct and clear: this Rite Hermétique was exported from Avignon to Paris, where in 1776 it formally changed its name to the Rite Ecossais Philosophique.

Therefore, the Philosophical Scottish Rite, in its original form, is nothing less than the "Masonic-ization" of Dom Pernety's personal alchemical and Swedenborgian philosophy. It was an alchemical society operating within the structure and framework of a Masonic Rite.

This is further confirmed by the organizational structure in Avignon. The high-grade system was "doubled" by a "loge de recherche" (research lodge) known as the Académie des Sages (Academy of Sages), also identified with the Academie des Vrais Maçons (Academy of True Masons). This was not a separate social club; it was the engine of the Rite's advanced work. Analysis of the degree structure suggests that the Rite's 7th degree, "Vrai Maçon" (True Mason), was identical with membership in this "Academy". This structure—a Blue Lodge base for all members, with an "Inner Order" or "Academy" for adepts pursuing the advanced esoteric (and in this case, alchemical) work—is a classic model for 18th-century Rosicrucian and esoteric fraternities. The REP is a perfect example of this model within the context of French Masonry.

Analysis of the Degree System

The degree structure of the Philosophical Scottish Rite is a primary source of its unique identity, though historical accounts have created some confusion. The Rite is built upon the foundation of the three symbolic "Blue Lodge" degrees: Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master. Above this, it established a system of hauts grades (high degrees), the number of which is variously cited as 6, 7 (according to Thory), 12, or 13 (by the archives of La Vertu Persécutée).

The most consistent lists, provided by 19th-century sources like Clavel and Mackey, consolidate these into a coherent 9-degree (post-Master) system, which, when added to the 3 symbolic degrees, accounts for the 12-degree total.

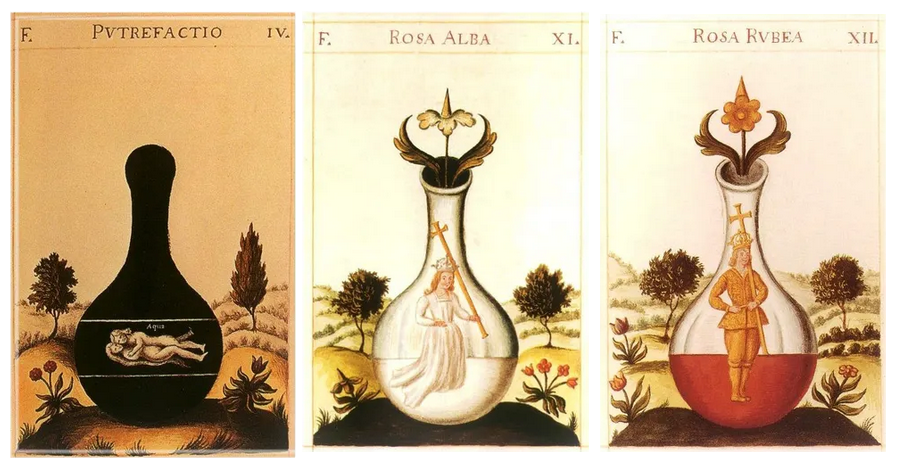

A critical analysis of these high degrees reveals that they are not a random collection of chivalric or philosophical titles. Instead, they form a sequential and coherent allegory for the Magnum Opus, or "Great Work," of alchemy. The entire high-grade system functions as a curriculum in alchemical theory and symbolism.

The following table reconstructs this high-grade system, synthesizing the lists found in the source materials and identifying the specific alchemical stage or symbol represented by each degree.

Reconstructed High-Grade System of the Rite Ecossais Philosophique

| Degree No. (Post-Master) | French Title | English Translation | Core Alchemical/Mythological Symbolism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | Chevalier de l'Aigle Noir, ou Rose-Croix d'Hérédom | Knight of the Black Eagle, or Rose-Croix of Heredom | The Nigredo (Blackening); the "putrefaction" or "black" stage of the Great Work, symbolized by the black eagle. |

| 4 | Chevalier du Phénix | Knight of the Phoenix | The Rubedo (Reddening); Rebirth from fire. Symbolizes the final perfection of the Work and the Philosopher's Stone. |

| 5 | Chevalier du Soleil | Knight of the Sun | Sol (Gold); The perfected metal. The alchemical goal of transmutation. A symbol of the perfected adept. |

| 6 | Chevalier de l'Iris | Knight of the Iris | The Cauda Pavonis (Peacock's Tail); The "rainbow" phase, a visual sign of the successful transition between stages of the Work. |

| 7 | Vrai Maçon | True Mason | The Adept or Philosopher; one who understands the Magnum Opus. Corresponds to the Académie des Sages. |

| 8 | Chevalier des Argonautes | Knight of the Argonauts | The Mythical Quest; The allegorical journey to obtain the Great Work. |

| 9 | Chevalier de la Toison d'Or | Knight of the Golden Fleece | The Goal Achieved; The Magnum Opus itself; the Philosopher's Stone, which Jason (the Argonaut) successfully acquired. |

This structure is profoundly revealing. The degrees are arranged as a step-by-step symbolic journey through the alchemical process. The Aigle Noir (Black Eagle) is a classic symbol for the nigredo (the blackening or putrefaction stage). The Iris represents the cauda pavonis (the peacock's tail), the multicolored "rainbow" phase that alchemists believed signaled the Work was proceeding correctly. The Phénix and Soleil (Sun) represent the final rubedo (reddening) and the attainment of Sol (Gold). The capstone degrees, Chevalier des Argonautes and Chevalier de la Toison d'Or (Knight of the Golden Fleece), are the most famous mythical-alchemical allegory for the quest and attainment of the Philosopher's Stone. This curriculum marks the REP as a system not just influenced by alchemy, but as alchemy, veiled in Masonic ritual.

The Chevalier de l’Aigle Noir (Rose-Croix)

The capstone and most emblematic degree of the Philosophical Scottish Rite is its version of the Rose-Croix, titled Chevalier de l’Aigle Noir Rose Croix (Knight of the Black Eagle Rose-Cross). This degree, more than any other, establishes the Rite's absolute uniqueness. It is explicitly stated that the REP's Rose-Croix has "nothing in common" with the classic French Rose-Croix (found in the Régulateur du Chevalier Maçon) that would become the 18th degree of the REAA.

This is not a simple variation; it is a complete and polemical re-grounding of the Rosicrucian symbol. It deliberately moves the degree away from the Christological mysticism of its contemporaries and back to its (supposed) roots in operative alchemy and Hermetic natural philosophy.

The goals of the REP's Rose-Croix chapter are stated without ambiguity: "to await the arrival of the sun in the twelve houses or figures of the zodiac" and, most importantly, "to extract from the four elements and the three kingdoms of nature... the famous Alkaest of the alchemists".

The very symbolism of the "Rose" and "Cross" is reinterpreted:

- The Cross: In the REAA, the cross is a symbol of Christ's suffering. In the REP, it is explicitly defined as the "symbol of the four elements".

- The Rose: In the REAA, it symbolizes the blood of Christ or the "New Law." In the REP, it is the "symbol of the triumph of the Work and the price of the wise".

The central legend of the degree is also replaced. Instead of the narrative of the "lost word" and the building of a new spiritual temple, the REP's degree is based on a tradition concerning Raymond Lulle, the 13th-century philosopher and alchemist. According to the ritual, Lulle used "Kabbalistic science" to create alchemical gold, which he presented to the King of England. The coins minted from this gold bore the Cross (four elements) and the Rose (triumph of the Work), and thus all who practice the "Kabbalistic science or Royal Art" (i.e., alchemy) are called "Chevaliers Rose-Croix".

The dominant symbols of the degree are likewise substituted:

- The Pelican (symbolizing Christ feeding his flock) of the REAA is replaced by the Black Eagle and the Phoenix.

- The Black Eagle is described as the "king of birds" and the only one able to "fly before the sun and fix its light"—a purely alchemical and cosmological symbol. It represents the nigredo stage, the raw, unpurified "matter" that must face the alchemical "sun" (fire).

- The Phoenix, which is reborn from its ashes, is linked to the property of gold, which is purified by fire. It is the emblem of the rubedo, the successful completion of the Work.

Finally, the "Sublime Goal" of the degree is defined as "the sublime science of the knowledge of nature," the "purification of imperfect metals" to transmute them into gold, and the magnetic extraction of the "universal medicine" from "potable gold". This is a literal, 18th-century description of the goals of operative alchemy. The REP, through this degree, was making a bold statement: "true" Rosicrucianism is not a mystical Christian order, but the "Royal Art" of physical and spiritual alchemy.

A Unique Ritualistic Identity

The radical philosophical divergence of the REP is reflected in its unique ritual practices, which set it apart from all mainstream Masonic systems. The differences are not merely aesthetic; they reconfigure the very cosmology of the lodge.

First is the Locus of Work. A foundational principle of the REP is that its lodges work "non le porche du temple, mais son dehors" (not in the temple porch, but outside it). This is a profound symbolic shift. Mainstream Masonry (whether REAA, York, or French Modern) symbolically places its members inside a representation of King Solomon's Temple, with the goal of morally or spiritually "rebuilding" it. The REP, by contrast, deliberately moves its members "outside" this structure. The ritualistic reason is given: "ce qui permet de contempler la Voûte Etoilée" (which allows contemplation of the Starry Vault).

This relocation changes the entire symbolic focus of the work. It is no longer architectural and moral (building an inner temple with tools like the square and compass). It becomes cosmological and natural (observing the cosmos and the forces of nature). The work is not about stone and mortar, but about stars and elements. This clearly distinguishes the Lodge (the assembly of Masons) from the Temple (the symbolic structure).

This cosmological focus is confirmed by the Rite's redefinition of the Three Great Lights. In mainstream Masonry, these are the Volume of the Sacred Law, the Square, and the Compass—symbols of moral, ethical, and spiritual guidance. The REP, however, defines its "Trois Grandes Lumières" as "le Soleil, la Lune et le VM (Vénérable Maître)" (the Sun, the Moon, and the Worshipful Master).

This substitution is the key to the entire Rite. The Sun (Sol) and Moon (Luna) are the two primary celestial and chemical agents of the alchemical "Great Work," representing the male and female, hot and dry, cool and moist principles. The Worshipful Master is thus repositioned. He is no longer just a "master" of a moral lodge; he is the Alchemist or Philosopher who observes, mediates, and guides these powerful natural forces. The REP's lodge is, therefore, a symbolic cosmological observatory and alchemical laboratory, where the adept learns to work with the forces of nature (Sun, Moon) to achieve the Magnum Opus.

This "scientific" and testing-oriented approach is also seen in the initiatory trials. The third journey of the candidate is described as "le plus terrible," involving a purification by fire that is "beaucoup plus pénible et éprouvant" (much more painful and trying) than in other rites and constitutes "la plus grande différence d'avec le rite français moderne". This is not a mere symbolic test of "perseverance"; it is a ritualistic calcination—an alchemical purification.

The Rite Through the French Revolution

The initial flowering of the Philosophical Scottish Rite in Paris, centered around its "chief seat" in the prestigious Loge du Contrat Social (Lodge of the Social Contract), was cut short by the political turmoil of the age. In 1792, as the French Revolution entered its most radical phase, the Rite "suspended its labors, in common with all the other Masonic Bodies of France".

The Rite lay dormant through the "Reign of Terror" and the subsequent rise of Napoleon. It was formally "resuscitated" at the termination of the Revolution's most chaotic period. In 1805, a significant reorganization took place in Paris. The Rite's pre-revolutionary chief seat, the Lodge of the Social Contract, joined forces with another prominent "Scottish" lodge, the Lodge of Saint Alexander of Scotland (Saint Alexandre d'Ecosse).

Together, these two lodges assumed the title of the "Mother Lodge of the Philosophic Scottish Rite in France".

This resurrected post-revolutionary body, however, appears to have undergone an intellectual shift. While the pre-1792 Avignon-based Rite was a "fringe" society of active esoteric practitioners and alchemical experimentalists (in the mold of Dom Pernety), the revived 1805 Parisian body is described as being "eminently literary in its character". This "literary" focus was bolstered by its possession of "a mass of valuable archives," which included "a number of old charters, manuscript rituals, and Masonic works of great interest, in all languages".

This description suggests a subtle but important transformation. The Rite, now centered in the imperial capital, may have evolved from a circle of quasi-operative alchemists into a more scholarly, archival, and "philosophical" (in the 19th-century sense) body. It became a curator and "heir" of the old Hermetic high grades, acting more as a historical and philosophical research society dedicated to preserving these unique rituals than as an active coven of practicing alchemists.

Comparative Analysis and Historical Relationships

The Philosophical Scottish Rite existed within the incredibly complex and competitive "Masonic marketplace" of late 18th and early 19th-century France. Its identity was forged in opposition to, and in competition with, the other major Masonic powers of its day.

Versus the Grand Orient de France (GOdF)

The REP's relationship with the Grand Orient de France (formed in 1773) was one of principled independence. The REP was, by its nature, part of the "Scottish" (i.e., high-grade, independent) camp that defined itself against the GOdF's centralizing authority. The REP's revived Mother Lodge "brought together Lodges that had refused to join the Grand Orient de France". This places the REP firmly within the "Masonic wars" of the 1770s and 80s, in which various "Scottish" Rites (those, like the REP, that focused on high-grade systems) resisted the GOdF's attempts to assert jurisdiction over all of French Masonry and its high degrees.

Versus the Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté (REAA)

The REP's relationship with the REAA is the most complex and ultimately fatal. The REAA was formed in Charleston, USA, in 1801 and brought to France by the Comte de Grasse-Tilly in 1804. The two Rites—the REP (est. 1776) and the REAA (in France, 1804)—were immediate competitors for the same "market": Masons who rejected the GOdF and sought initiation into a comprehensive "Scottish" high-grade system.

For a time, the two Rites coexisted with a degree of mutual recognition. In a telling historical note, members holding the high grades of the REP (listed as GIIC of the La Paix and La Candeur lodges) were, "without the slightest problem, admitted directly to the 32e degré du REAA". This act, however, was less an expression of fraternity and more a brilliant "merger and acquisition" tactic by the REAA.

By recognizing the REP's summit as equivalent to its own penultimate degree (the 32°), the REAA implicitly positioned itself as the superior and more complete system, offering the "final" 33rd degree, which the REP lacked. This, combined with the REAA's superior organization and its 33-degree structure that incorporated elements from many other Rites, made it an overwhelmingly attractive alternative.

The REP, as a smaller, more esoterically niche and "literary" body, could not compete. Its members "rallièrent assez vite au Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté" (rallied pretty quickly to the REAA). The REAA effectively "won" the battle to be the premier "Scottish" Rite in France. This absorption was finalized when the REP's Mother Lodge, the Contrat Social, "finit par cesser ses activités en 1826" (finally ceased its activities in 1826), marking the effective end of the Philosophical Scottish Rite in France.

The profound differences between the REP and its chief contemporaries are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of 18th/19th-Century French-based Rites

| Feature | Rite Ecossais Philosophique (REP) | Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté (REAA) | Rite Ecossais Rectifié (RER) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Alchemical/Hermetic Natural Philosophy | Syncretic Moral, Chivalric & Kabbalistic Philosophy | Martinist Theurgy & Christian Chivalry (Willermoz) |

| Key "High Degree" | Chevalier de l'Aigle Noir | Chevalier Rose Croix (18°) | Chevalier Bienfaisant de la Cité Sainte (CBCS) |

| Symbolism of "Rose-Croix" | Alchemical: (Raymond Lulle; Cross, 4 Elements; Rose , "Triumph of the Work") | Christological: (Pelican feeding young; INRI; New Law of Love) | N/A (System capstone is chivalric) |

| "Great Lights" | Cosmological: (Sun, Moon, Worshipful Master) | Moral: (Volume of Sacred Law, Square, Compass) | Theurgical: (Volume of Sacred Law, Square, Compass) |

| Ritual Locus | Outside the Temple (to see the "Starry Vault") | Inside the Temple (to rebuild it) | Inside the Temple |

| Historical Fate in France | Absorbed by REAA; Mother Lodge dissolved 1826 | Became the dominant global high-grade system | Persists as a distinct, self-contained Rite |

The Belgian Bastion and Modern Legacy

While the Philosophical Scottish Rite was effectively absorbed into extinction in France by 1826, this was not the end of its history. As previously noted, the Rite had spread from Avignon into the Low Countries in the late 18th century.

Its survival was secured in Belgium. The REP was practiced by the lodge Les Frères Réunis (The Reunited Brothers) in Tournai. In 1838, this lodge took a highly significant and deliberate action: it "prendra le titre de Mère Loge du Rite Ecossais Philosophique" (would take the title of Mother Lodge of the Philosophical Scottish Rite).

The timing of this event is critical. It occurred twelve years after the Parisian Mother Lodge (Contrat Social) had dissolved. This was a formal "claim to sovereignty." The lodge in Tournai, seeing the "mantle" of the Rite abandoned in France, declared itself the new world headquarters and legitimate successor of the original Avignon-Paris tradition.

This transmission of authority from France to Belgium ensured the Rite's survival, albeit in an obscure form. This Belgian lineage is the thread of its modern continuity. While the REP is not widely practiced today, its legacy appears to be concentrated in this Belgian line. The establishment of the Souverain Collège du rite écossais pour la Belgique (Sovereign College of the Scottish Rite for Belgium) on December 9, 1962, is almost certainly a 20th-century revival and re-organization of this specific, historical Belgian-based lineage, tracing its authority back to the 1838 declaration by Les Frères Réunis in Tournai.

The Enduring Significance of a Philosophic Rite

The Rite Ecossais Philosophique represents a crucial, "road not taken" in the dominant history of Freemasonry. It stands as a "Masonic time capsule" of 18th-century "alchemical Masonry" in its most unabashed and intellectually coherent form.

During the 18th century, numerous esoteric systems vied for prominence within the Masonic lodge structure. Most of these eventually met one of three fates:

The REP resisted all three of these fates. It refused to be merely moral allegory, it rejected the explicitly Christian path of the RER, and it "failed" to compete with the organizational might of the REAA.

Paradoxically, its historical "failure" in France—its absorption by the REAA—is precisely what preserved its esoteric purity. It was not diluted, compromised, or re-written to fit a broader, more palatable system. It remains a perfect, "frozen" specimen of the 18th-century Hermetic synthesis that united the Masonic lodge, Swedenborgian mysticism, and alchemical philosophy.

Its legacy, therefore, is not found in a large global membership or a vast institutional structure. Its enduring significance lies in its singularity. It is a complete esoteric curriculum in Masonic form, a Rite where the lodge is an observatory, the "Lights" are the cosmic forces of Sol and Luna, and the goal of the adept is the "triumph of the Work": the creation of the Philosopher's Stone and the "universal medicine". It remains a testament to a time when Freemasonry was not just a "system of morality," but a "sublime science of the knowledge of nature"

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴