Free-Masonry, the Army, and the Affair of the Cards

A true Masonic conspiracy?

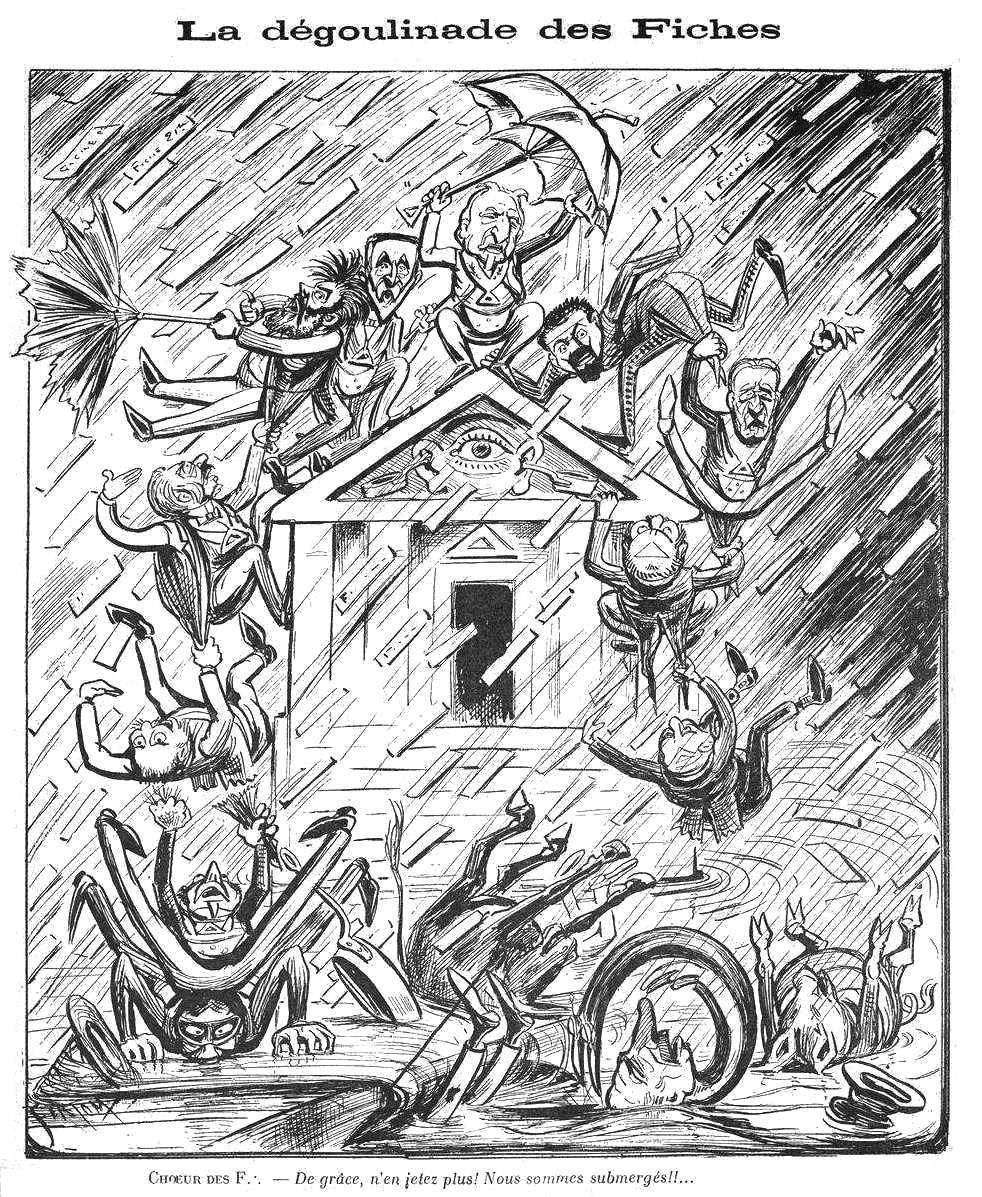

In the autumn of 1904, a political scandal of extraordinary proportions erupted in Paris, shaking the French Third Republic to its foundations. Known as the Affaire des Fiches (the Affair of the Cards), and sometimes more colloquially as the Affaire des Casseroles, the crisis exposed a vast, clandestine system of political and religious surveillance operating at the heart of the French Army. For four years, the Ministry of War, under the direction of General Louis André, had collaborated with the Masonic lodges of the Grand Orient de France to compile secret files on thousands of army officers. These files, or fiches, bypassed the official chain of command, cataloging officers' private lives—their religious practices, their wives' piety, the schools their children attended—to determine their political loyalty to the Republic. On the basis of this covert intelligence, careers were made and broken, with promotions granted to proven republicans and withheld from practicing Catholics and suspected reactionaries.

The affair was not merely a case of bureaucratic overreach or an isolated conspiracy. It was the explosive culmination of the deep-seated ideological battles that had defined the Third Republic since its inception. The central conflict it laid bare was that of a republican government which, feeling besieged by its traditional enemies—a monarchist-leaning military and the powerful Catholic Church—resorted to profoundly illiberal means to secure its own survival. The scandal cannot be understood outside the context of the national trauma that preceded it: the Dreyfus Affair. That decade-long struggle had cleaved the nation into two warring camps, pitting a republican, anticlerical vision of France against a conservative, Catholic, and nationalist one. The eventual victory of the Dreyfusards brought to power a left-wing coalition, the Bloc des gauches, animated by a militant desire to defend the Republic by neutralizing the institutions that had opposed them. The Affaire des Fiches represented a critical evolution of this "republican defense" strategy. It marked a transition from a defensive posture, focused on rectifying a specific injustice, to a proactive and offensive campaign to purge perceived enemies from the levers of state power. The filing system was, in essence, the administrative weaponization of the Dreyfus-era ideological divide, a calculated political tool designed to consolidate the Dreyfusard victory.

While often overshadowed by the sheer drama of the Dreyfus case, the Affaire des Fiches is essential for understanding the militant nature of French secularism (laïcité) and the complex, often paradoxical, relationship between republican ideals and the exercise of state power. It revealed a government willing to sacrifice the principles of individual liberty and freedom of conscience on the altar of political security. The affair stands as a profound cautionary tale, a moment when the French Republic, in its fervent quest to protect itself, adopted the very methods of secret denunciation and ideological policing characteristic of the authoritarian regimes it defined itself against.

The Shadow of Dreyfus – A Republic on the Defensive

The clandestine surveillance system that came to light in 1904 was not conceived in a vacuum. Its origins lay in the deep fissures of French society, which had been torn open and exposed by the Dreyfus Affair a decade earlier. The wrongful conviction of Captain Alfred Dreyfus for treason in 1894, and the subsequent battle for his exoneration, was more than a miscarriage of justice; it was a national cataclysm that forced a painful reckoning with the core values of the Third Republic. The trauma of the affair created an atmosphere of profound and lasting suspicion, convincing the victorious republican government that the army was a hostile and untrustworthy institution, a "state within a state" that required radical "purification" to ensure its loyalty.

A Nation Divided

The Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906) was the crucible in which the political identities of early 20th-century France were forged. It split the nation into two irreconcilable camps, often referred to as the "two Frances," each animated by a fundamentally different vision of the nation's soul.

On one side stood the "anti-Dreyfusards," a powerful bloc comprising the military high command, the Catholic Church, monarchists, and a burgeoning nationalist movement. For this coalition, the honor and integrity of the army were sacrosanct, representing the last bastion of national pride after the humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. They viewed any attempt to question the court-martial's verdict as a subversive attack on the nation itself, an effort by France's enemies to weaken and discredit its most vital institution. This camp was animated by a virulent strain of antisemitism, which had been gaining ground since the publication of Édouard Drumont's La France Juive in 1886. Newspapers like Drumont's La Libre Parole relentlessly portrayed Dreyfus, an assimilated Jewish officer from Alsace, as the archetypal traitor, symbolizing the supposed disloyalty of all French Jews. The anti-Dreyfusards clung to the original verdict, even in the face of mounting evidence of forgery and a cover-up, because to admit error would be to undermine the authority of the army and the traditional social order it represented.

Opposing them was a diverse coalition of "Dreyfusards," which brought together moderate republicans, Radicals, socialists, and prominent intellectuals like Émile Zola. For the Dreyfusards, the case was not merely about the guilt or innocence of one man; it was a fundamental test of the Republic's commitment to its founding ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. They argued that the principles of justice, truth, and the rights of the individual must prevail over abstract notions of national security or reasons of state. They saw the anti-Dreyfusard camp as a reactionary force seeking to roll back the legacy of the French Revolution and subordinate the Republic to the authority of the army and the Church.

The struggle was long and bitter, playing out in the press, in the streets, and in the corridors of power. The eventual victory of the Dreyfusards—marked by Dreyfus's presidential pardon in 1899 and his full legal exoneration in 1906—was not a moment of national healing. Instead, it was a decisive political triumph for the anticlerical Left. The affair consolidated the legitimacy of the Third Republic, marginalized its monarchist and conservative opponents, and brought to power a series of Radical-led governments determined to settle scores with the institutions that had fought so fiercely to condemn an innocent man. This victory, however, was born of conflict and left a legacy of deep-seated animosity and a powerful desire to neutralize the vanquished forces of the anti-Dreyfusard coalition.

A "State Within a State"

At the center of the republican government's anxieties was the French Army. The Dreyfus Affair had stripped away the army's veneer of patriotic impartiality, revealing an officer corps that was widely seen as a bastion of conservative, aristocratic, and Catholic values, fundamentally hostile to the parliamentary republic. The military leadership, still haunted by the national humiliation of 1870, was pathologically obsessed with its own honor and institutional autonomy. This obsession led the general staff not only to make a catastrophic initial judgment in the Dreyfus case but to actively forge evidence, suppress the truth, and persecute honest officers like Colonel Georges Picquart who sought to expose the injustice.

For the victorious republicans, the army's conduct was proof that it operated as a "state within a state" (un État dans l'État), an unaccountable and dangerous instrument of power populated by men whose loyalties lay with the Church and a defunct monarchy rather than with the Republic they were sworn to serve. Republicans feared that this reactionary officer corps could, under the right circumstances, support a military coup or a monarchist restoration, as had been threatened during the Boulangist crisis of the late 1880s.

Consequently, the governments that came to power in the wake of the affair, first under Prime Minister Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau and then his more radical successor Émile Combes, saw it as their primary mission to assert civilian political control over the military. The goal was to "republicanize" the army—to break the hold of the traditionalist elites and ensure that the officer corps reflected the political values of the regime it served. This imperative to purge the army of its anti-republican elements became the central justification for the extraordinary measures that would soon be undertaken by the Minister of War, General André.

The War on the Church, using Laïcité as a Political Weapon

The other great enemy of the Republic, in the eyes of the Dreyfusards, was the Catholic Church. The Church's hierarchy and its influential press, particularly the Assumptionist fathers and their newspaper La Croix, had been among the most virulent anti-Dreyfusards, using the affair to attack the secular Republic and fan the flames of antisemitism. This confirmed, for the anticlerical Left, that the Church was an implacable foe of republican values, an institution dedicated to obscurantism and reaction.

The political ascendancy of the Left after 1899 therefore unleashed a period of intense anticlerical legislation, a veritable war on the Church's influence in French society. This campaign was spearheaded by Prime Minister Émile Combes, who took office in 1902. Combes, a former seminarian who had abandoned his vocation before ordination, became a Freemason and a passionate advocate for a strictly secular state. His government, the Bloc des gauches, was cemented by a shared commitment to anticlericalism.

Under Combes's leadership, the government aggressively applied the 1901 Law of Associations to refuse authorization to and effectively expel thousands of members of religious teaching orders from France, closing nearly 10,000 religious schools in the process This legislative assault precipitated a rupture in diplomatic relations with the Holy See in 1904 and culminated in the landmark 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, which formally abrogated Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 and established the principle of laïcité as the backbone of the French state.

The Affaire des Fiches was an integral, if secret, component of this broader anticlerical crusade. The logic of the Combes government's position was that an officer's Catholicism was not a private matter of faith but a reliable political indicator of anti-republican sentiment. The army was one of the last major state institutions where the influence of the Church and its traditionalist values remained deeply entrenched. Therefore, to successfully "republicanize" the army, it was deemed necessary to de-Catholicize its leadership. The government and its allies came to believe that a "good Catholic" officer, educated in religious schools and loyal to the Church, could not simultaneously be a "good Republican" officer, loyal to the secular state. The secret filing system was the practical, clandestine tool designed to achieve this political and ideological purification, making the Affaire des Fiches a covert front in the government's public war against the Church.

The Masonic Machinery of Surveillance

The decision to systematically vet the French officer corps for political loyalty required a mechanism of surveillance that was both comprehensive and clandestine. The official military hierarchy was deemed part of the problem, its reports tainted by the very clerical and conservative biases the government sought to overcome. To create a parallel system of intelligence, the Minister of War turned to an organization with a nationwide network, a shared ideological commitment to the secular Republic, and a culture of secrecy: the Grand Orient de France. This alliance between a government ministry and a Masonic obedience gave birth to a remarkable apparatus of political espionage, designed to control the French military from within.

The Architect - General Louis André, Minister of War

The instigator and driving force behind the filing system was General Louis Joseph Nicolas André, who was appointed Minister of War in May 1900 in the "Republican Defense" cabinet of Waldeck-Rousseau. André was not a typical product of the army's conservative high command. A graduate of the prestigious École Polytechnique, he was a Freemason, fiercely loyal to the Third Republic, and a militant anticlerical who viewed the Catholic Church's influence as a poison in the life of the nation.

Upon taking office, André was tasked with the formiable challenge of bringing the army to heel. He was convinced that the traditional system of promotions, which relied on the assessments of senior commanders, was hopelessly compromised. He believed it systematically favored officers from aristocratic and Catholic backgrounds while penalizing those with known republican or "free-thinking" sympathies. To break this conservative grip and ensure that the army's leadership was politically reliable, André concluded that he needed an alternative, secret source of information. He required intelligence on the private lives and political opinions of his officers, data that would allow him to bypass the official channels and make promotion decisions based on a single criterion: loyalty to the Republic.

This quest for a parallel intelligence network led him directly to the headquarters of the Grand Orient de France on the Rue Cadet in Paris.

Freemasonry and the Grand Orient de France as a State Security Apparatus

General André found a willing and able partner in the Grand Orient de France, the largest and most politically influential Masonic body in the country. By the turn of the 20th century, French Freemasonry, particularly the Grand Orient, was ideologically aligned with the Radical Party and the anticlerical Left. In 1877, it had removed the requirement for its members to believe in God, affirming its commitment to "absolute freedom of conscience" and positioning itself as a philosophical bulwark of the secular Republic against the "obscurantism" of the Catholic Church. The Grand Orient saw itself as a guardian of republican values, and its members, drawn largely from the middle classes of teachers, lawyers, and civil servants, were deeply embedded in the political life of the Bloc des gauches.

When General André approached the Grand Orient's president, Frédéric Desmons, with his request for assistance, the leadership was receptive. The operation was established with the utmost secrecy. To maintain confidentiality, the Grand Orient's supreme body, the Council of the Order, was not formally consulted. Instead, the council's executive office gave its authorization, and only the most trusted presidents of local lodges were contacted directly to participate.

The operational hub for the scheme was the Grand Orient's headquarters in Paris. Information gathered by lodges in garrison towns across France was sent in anonymous forms to the central office. There, the operation was managed by the Grand Orient's powerful Secretary, Narcisse Vadecard, and his trusted assistant, Jean-Baptiste Bidegain. They were responsible for centralizing the thousands of incoming reports, having them typed onto standardized index cards (fiches), and then forwarding the completed files to General André's cabinet at the Ministry of War.

The Grand Orient never saw its actions as improper espionage. It framed its participation as a patriotic duty, a necessary "small measure" to help "save the Republic from its eternal enemies". When the scandal later broke, the organization's official manifesto expressed no remorse. Instead, it displayed what was described as "a hint of aggression and pride in the action taken," arguing that the real crime was not the surveillance itself but the betrayal of the leaker, Bidegain, whom they denounced as a "traitor and scoundrel bribed by the money of the Congregationalists". For the Grand Orient, this was not a conspiracy against the state; it was a clandestine operation in defense of the state against its internal foes.

Bureaucratizing Discrimination

For four years, from 1900 to 1904, this Masonic machinery of surveillance operated smoothly and efficiently. The network of lodges compiled approximately 20,000 fiches on some 19,000 officers, creating a comprehensive secret database on the army's leadership.

The information collected was intensely personal and focused almost exclusively on political and religious indicators. Masonic agents in provincial towns became spies, observing the private conduct of local officers and their families. Their reports, recorded on the fiches, noted whether an officer attended Mass, often with coded abbreviations like "VLM" for Va à la messe ("Goes to Mass") or "VLM AL" for Va à la messe avec un livre ("Goes to Mass with a book"). They documented whether an officer's wife and children were pious, whether he sent his children to Catholic schools or secular state schools, what newspapers he read, and with whom he associated socially. The notes were often laced with derogatory anticlerical slang, labeling officers as "clérical clericalisant" (clerical and clericalizing), "cléricafard" (a pejorative for "pious hypocrite"), or "cléricanaille" ("clerical scoundrel").

At the Ministry of War, this raw intelligence was systematized into a tool for managing promotions. Each officer's file was reviewed, and his card was marked with one of two classifications: "Corinth" or "Carthage".

- Corinth: This designation was for the officers deemed politically reliable. A Freemason, a known "free-thinker," or an officer with "excellent [republican] opinions" would be marked as a Corinthian and placed on the fast track for promotion.

- Carthage: This designation was for the "goats," who were to be held back. An officer could be an exemplary soldier, "perfect in all respects" according to his official reports, but would be branded a Carthaginian and have his career stalled simply because he "went to Mass with his family" or educated his children in Catholic schools. A bachelor officer who attended Mass was, by the system's logic, "by definition of a reactionary disposition".

This system reveals the totalitarian logic that had taken root within the "republican defense" movement. It institutionalized a regime of thought-crime, where an individual's private beliefs and personal conduct were treated as definitive evidence of their political loyalty or potential for treason. The state, acting through its Masonic proxy, was systematically penetrating the most private spheres of life—family, faith, and education—to enforce ideological conformity. This was not merely an effort to prevent a military coup; it was an attempt at social engineering, aimed at creating a perfectly loyal, ideologically homogenous officer corps. In its zealous campaign to defend itself from its enemies, the Republic was adopting the intrusive surveillance methods characteristic of the very authoritarian regimes it claimed to oppose, creating a profound and damning contradiction with its own liberal principles.

Key Figures in the Affair of the Cards

| Name | Title / Role | Affiliation | Significance in the Affair |

|---|---|---|---|

| Émile Combes | Prime Minister of France (1902-1905) | Government (Radical Party), Grand Orient de France | As head of the Bloc des gauches government, he presided over the aggressive anticlerical campaign and was the ultimate political authority behind the filing system. The scandal led directly to his resignation and the fall of his cabinet. |

| General Louis André | Minister of War (1900-1904) | Government, French Army, Freemason | The architect and instigator of the Affaire des Fiches. He established the partnership with the Grand Orient to "republicanize" the army and was forced to resign in disgrace when the system was publicly exposed. |

| Jean Guyot de Villeneuve | Nationalist Deputy, Chamber of Deputies | Parliament (Nationalist Right) | A former army officer, he purchased the leaked files from Bidegain and exposed the scandal on the floor of the Chamber of Deputies on October 28, 1904, initiating the political crisis that would topple the government. |

| Jean-Baptiste Bidegain | Assistant Secretary, Grand Orient de France | Grand Orient de France | The whistleblower. Despite being a high-ranking Mason, he was reportedly "appalled" by the scheme and leaked thousands of fiches to the opposition, leading to the scandal's public exposure. He was branded the "Judas of the Grand Orient" by his former brethren. |

| Narcisse Vadecard | Secretary, Grand Orient de France | Grand Orient de France | Bidegain's superior, he was a key manager of the filing system at the Grand Orient's headquarters, centralizing the information from the lodges before it was transmitted to the Ministry of War. |

| Gabriel Syveton | Nationalist Deputy, Chamber of Deputies | Parliament (Ligue de la patrie française) | A vocal nationalist who physically assaulted General André in the Chamber during the heated debate of November 4, 1904. He died under mysterious circumstances the day before he was due in court for the assault. |

The Scandal Erupts

For four years, the alliance between the Ministry of War and the Grand Orient operated in the shadows, its secret files reshaping the French military's command structure one promotion at a time. But such a vast system of denunciation, involving thousands of individuals, could not remain secret forever. In the autumn of 1904, the clandestine machinery was brought down not by an external investigation, but by a crisis of conscience from within its own ranks. The public unveiling of the affair was a dramatic and rapid sequence of events, a political firestorm that consumed its creators and brought down the most powerful anticlerical government in the history of the Third Republic.

A Crisis of Conscience in the Grand Orient of France

The catalyst for the scandal was Jean-Baptiste Bidegain, the assistant secretary of the Grand Orient de France and a key administrator of the filing system alongside his superior, Narcisse Vadecard. Despite his high-ranking position within Freemasonry, Bidegain grew increasingly "appalled" by the scale and nature of the espionage network he was helping to manage. His motives remain a subject of historical debate—whether driven by a genuine crisis of conscience, personal ambition, or financial need—but his actions were decisive.

Bidegain made contact with a prominent member of the parliamentary opposition, Jean Guyot de Villeneuve, a nationalist deputy and former army officer who harbored a deep animosity toward the Combes government and its policies. In a series of clandestine meetings, Bidegain agreed to betray his organization. For a reported sum of 40,000 francs, he sold Guyot de Villeneuve a massive cache of the secret documents: thousands of original fiches, letters, and correspondence between the Masonic lodges and General André's cabinet at the Ministry of War.

Bidegain's defection armed the government's political enemies with irrefutable proof of the secret system. His actions also signaled a profound internal conflict within the republican camp, pitting the partisan commitment to the Combes government against the foundational republican principles of liberty and freedom of conscience, which the filing system so flagrantly violated.

October 28, 1904

Armed with Bidegain's explosive documents, Jean Guyot de Villeneuve chose the most public stage in France to detonate his political bomb: the floor of the Chamber of Deputies. On October 28, 1904, during an interpellation of the government, he rose to speak and publicly revealed the existence of the secret filing system. He accused General André and the Grand Orient of operating a vast political and religious espionage network to illegally influence army promotions. Reading from the fiches themselves, he detailed the intrusive surveillance of officers' private lives, shocking the assembly with the petty and personal nature of the denunciations.

Initially, the government attempted to brazen out the crisis. Prime Minister Combes and General André flatly denied the accusations, dismissing them as unsubstantiated slander from their nationalist political opponents. The defense was a calculated risk, predicated on the assumption that Guyot de Villeneuve was bluffing or that his proof was flimsy. It was a miscalculation that would prove fatal.

November 4, 1904

The political crisis reached its climax a week later, during the parliamentary session of November 4. The chamber was packed and electric with anticipation. Guyot de Villeneuve once again took the rostrum, but this time he held the government's fate in his hands. He produced definitive, irrefutable proof: a letter, torn in half and reassembled, that directly implicated General André in the management of the system, proving his direct knowledge and complicity.

The revelation shattered the government's denials and sent the chamber into an uproar. The session descended into chaos. As General André sat stunned on the ministers' bench, the nationalist deputy Gabriel Syveton, a fiery orator and member of the right-wing Ligue de la Patrie Française, strode across the floor and slapped the Minister of War squarely across the face. The act of physical violence triggered a full-blown brawl in the heart of the French legislature, with deputies exchanging blows and grappling on the floor.

This moment of pandemonium, broadcast across the country by an astonished press, symbolized the complete breakdown of political decorum and the raw fury the scandal had unleashed. The government managed to survive a subsequent vote of confidence by a razor-thin margin of just two votes, but its moral and political authority was irrevocably shattered. The image of the Minister of War being physically assaulted in parliament was an indelible stain of humiliation.

Resignations and Collapse

In the wake of the tumultuous November 4 session, the government's position rapidly disintegrated. Exposed and publicly humiliated, General André had no choice but to resign as Minister of War on November 15. His departure was a tacit admission of guilt that further weakened the beleaguered Combes cabinet.

Meanwhile, the press, both on the right and in the center, had a field day, relentlessly publishing the contents of the leaked fiches for a scandalized public. The revelations sparked widespread outrage that transcended typical political divides. Even many committed republicans and anticlericals were disgusted by the government's methods, viewing the system of secret denunciation as an intolerable violation of individual privacy and religious freedom, reminiscent of the worst excesses of the monarchy or the Reign of Terror.

The public outcry caused the Bloc des gauches coalition to fracture. Prime Minister Combes's socialist allies in parliament, led by Jean Jaurès, had initially supported the government, but they found it politically impossible to continue defending such a sordid system of spying and denunciation. Facing the loss of his parliamentary majority and with his authority in tattered, Émile Combes and his entire government submitted their resignation on January 17, 1905.

The Affaire des Fiches had claimed its ultimate political victim.

Timeline of the Scandal's Unveiling (October 1904 – January 1905)

| Date | Event | Immediate Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Oct 28, 1904 | Deputy Jean Guyot de Villeneuve reveals the existence of the fiches in the Chamber of Deputies, reading examples of the secret files. | The government denies the allegations, attempting to dismiss them as politically motivated slander, but a major political crisis begins. |

| Nov 4, 1904 | Guyot de Villeneuve presents definitive documentary proof directly implicating Minister of War André. Deputy Gabriel Syveton slaps André in the face. | Pandemonium erupts in the Chamber, including a physical brawl. The government barely survives a confidence vote, but its credibility is destroyed. |

| Nov 15, 1904 | General Louis André officially resigns as Minister of War. | The government is severely weakened, losing the architect of the filing system and effectively admitting the substance of the scandal. |

| Dec 8, 1904 | Gabriel Syveton is found dead in his study from asphyxiation, an apparent suicide, on the very day he was scheduled to appear in court for his assault on André. | The nationalist camp alleges a Masonic assassination, further inflaming public passions and fueling conspiracy theories surrounding the affair. |

| Jan 17, 1905 | Having lost the support of his socialist coalition partners and facing unrelenting public pressure, Prime Minister Émile Combes and his entire cabinet resign. | The Bloc des gauches government, the most aggressively anticlerical in the Third Republic's history, collapses as a direct result of the scandal. |

Legacy and Consequences

The fall of the Combes government marked the immediate political climax of the Affaire des Fiches, but its repercussions extended far beyond the winter of 1904-1905. The scandal left deep and lasting scars on French political culture, on the military, and on the very definition of republicanism. It forced a painful reckoning with the methods used to defend the Republic and sowed seeds of distrust and cynicism that would linger for decades. While the system of the fiches was dismantled, its legacy of politicization and moral compromise would prove far more difficult to erase.

A Moral Crisis for the Republican Left

For the broad coalition of the republican Left, the scandal was a profound moral and political catastrophe. It created a deep crisis within the Dreyfusard camp, which had, only a few years earlier, waged a heroic battle for justice, truth, and individual rights against an oppressive state apparatus. Now, the very same political forces were exposed as having created their own secret police system to enforce ideological conformity through methods of spying and denunciation. The hypocrisy was stark and damaging.

The affair forced a painful and divisive debate over the means and ends of "republican defense." Was it legitimate to use illiberal, intrusive methods to protect a liberal republic from its perceived enemies? This question fractured the unity of the Bloc des gauches. Many republicans who had supported Combes's anticlerical policies could not stomach the secret surveillance of the fiches. The scandal tarnished the moral high ground that the Dreyfusards had won, demonstrating that the temptation to abuse power was not exclusive to the political Right. It revealed a troubling authoritarian streak within the anticlerical movement, suggesting that their commitment to "freedom of conscience" did not always extend to those with whom they disagreed, particularly observant Catholics. This moral crisis weakened the cohesion of the Left and contributed to a more moderate political climate under Combes's successor, Maurice Rouvier.

The Politicized Officer Corps on the Eve of War

While the affair achieved its immediate goal of breaking the conservative, Catholic monopoly on high command, its long-term consequences for the French military were deeply corrosive. The purge of anti-Dreyfusard officers and the promotion of those deemed politically loyal were accomplished, and many of the old guard were removed from positions of authority. However, this "republicanization" came at a steep price.

The scandal shattered morale and fostered a climate of deep cynicism, suspicion, and resentment within the officer corps. It sent a clear message that an officer's career advancement depended less on professional merit, tactical skill, or leadership ability than on his political connections and ideological purity as judged by anonymous spies. This politicization of the promotion process undermined the army's institutional cohesion and esprit de corps. Officers now had to be wary of their colleagues, who might be reporting on their private conversations in the mess hall. The affair created lasting divisions between the "fichés" (those who benefited from the system) and the "fichards" (those who were its victims), poisoning relationships within the military hierarchy for years to come.

This damage was inflicted at a particularly dangerous moment in European history. Less than a decade before the outbreak of the First World War, as an arms race with Germany was accelerating, the French army's leadership was being reshaped by a political purge. The affair prioritized political loyalty over military effectiveness, a perilous trade-off for a nation facing a formidable external threat. While it is impossible to draw a direct causal line, the deep divisions and the emphasis on political criteria over professional competence arguably weakened the French high command in the critical years leading up to the cataclysm of 1914.

The "Affair of the Casseroles" why that name?

The scandal's alternative name, the Affaire des Casseroles, is itself a powerful indicator of its public perception and legacy. The term derives from the French idiom traîner des casseroles, which literally means "to drag saucepans." Figuratively, it refers to being burdened by a noisy, compromising, and shameful scandal from one's past, evoking the image of saucepans being tied to an animal's tail to create a clattering, inescapable racket. A politician who "drags casseroles" is one with a history of malfeasance that clings to them and tarnishes their reputation.

The application of this name to the Affaire des Fiches is highly significant. It suggests that, in the public mind, the defining characteristic of the scandal was not its ideological justification but its crude, loud, and deeply embarrassing nature. Unlike the Dreyfus Affair, which was ultimately framed by its supporters as a noble and epic battle for justice and truth, the Affair of the Cards was widely seen as a sordid, grubby, backroom plot. The name captures the sense of public humiliation and the lasting stain it left on the Combes government and its allies in the Grand Orient. It was not a grand ideological confrontation but a "bad affair" (mauvaise affaire) that was simply shameful. The clatter of the "casseroles" was the sound of the Republic's own dirty laundry being aired in public, a noisy reminder of a moment when its defenders had betrayed its highest ideals.

A Pyrrhic Victory for the Republic?

The Affaire des Fiches stands as a pivotal and deeply paradoxical moment in the history of the French Third Republic. It was a crisis where the state, in its fervent quest to secure itself against internal enemies, ultimately betrayed its own founding principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The government of Émile Combes and its allies in the Grand Orient de France succeeded in their immediate political objectives. They decisively broke the conservative and clerical hold on the army's high command, accelerated the "republicanization" of a key state institution, and helped create the political momentum that led to the landmark 1905 law on the separation of Church and State—a cornerstone of modern French secularism.

However, this was a Pyrrhic victory, achieved at a tremendous moral and institutional cost. By creating and operating a system of secret denunciation based on religious belief and private opinion, the government and its Masonic partners employed the very tools of oppression they had once so righteously fought against during the Dreyfus Affair. They sacrificed the principle of freedom of conscience for the sake of political expediency, and in doing so, they tarnished the moral authority of the republican cause.

The scandal left behind a bitter and complex legacy. It fueled a lasting cynicism about the integrity of the political class and deepened the ideological divides within French society. It inflicted serious damage on the French military, creating a climate of suspicion and resentment and prioritizing political loyalty over professional competence at a critical juncture in European history. Most profoundly, the Affaire des Fiches serves as a timeless cautionary tale about the perils of political paranoia and the enduring tension that exists between the defense of a liberal democracy and the seductive temptation of authoritarian methods. It demonstrated with stark clarity that no political ideology, however noble its stated aims, is immune to the corruption of power, and that the greatest threat to a republic can sometimes come not from its declared enemies, but from its own zealous defenders.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴