Sacred Order of the Sophisians

(Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens) 1801

The Cult of Wisdom in Napoleonic Paris

The Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens (The Sacred Order of the Sophisians), a highly specialized and short-lived Masonic society, emerged in Paris in 1801, positioning itself at the confluence of post-Revolutionary political upheaval, Napoleonic expansionism, and the flourishing European obsession with antiquity known as Egyptomania. While the Order’s existence spanned only a few years, its foundation and rituals provide historians with a unique cultural index of the era, reflecting the profound intellectual tensions inherent in late Enlightenment and post-Revolutionary France. These tensions revolved around the attempt to reconcile scientific Reason with imported mysticism, vitalism with empirical science, and the political objectives of the West with the perceived ancient wisdom of the East.

The Sophisians were formally founded by Venerable Brother Cuvelier de Trie. Cuvelier de Trie was a well-known playwright, authoring over a hundred dramas and melodramas popular on the Parisian stage, particularly at the Théâtre de L'Ambigu-comique. This background in dramatic production is fundamental to understanding the nature of the Sophisian rituals, which were inherently theatrical and focused on aesthetic presentation rather than strictly philosophical or operative Masonic goals.

The Order was established within the existing Masonic framework of the Loge des Frères-Artistes (Brother Artists) and operated under the broader auspices of the Grand Orient de France (GOdF). Its core symbolism was overtly built upon imaginative constructs regarding Ancient Egypt and, specifically, the enduring Roman-era cult of Isis. The historical significance of the Sophisians, as revealed through academic study, lies less in its esoteric longevity and more in its direct function as a cultural barometer for the Napoleonic regime, channeling the psychological and political fallout of the failed Egyptian military campaign (1798–1801) into a formalized ritual structure. The Sophisians were a critical, if transient, bridge institution, employing a Masonic structure to house a radical, purely Egyptian, and intensely performative ritual content.

The Egyptian Catalyst

The foundation of the Sacred Order of the Sophisians was a direct cultural consequence of Napoleon Bonaparte’s military and scientific expedition to Egypt, which lasted from 1798 to 1801. Although the campaign ended in military defeat, Napoleon ensured that it was equally a cultural undertaking, bringing 167 scholars and artists, known as the savants, who meticulously studied and documented ancient Egyptian history and culture.

The Aftermath of the Campaign

When military officers, generals, and savants returned to France, their experiences catalyzed a massive wave of Egyptomania. Contemporary accounts noted that the capital was engulfed in Egyptian culture, driving trends in the arts and literature. The city of Paris itself was romantically recast as «Bar-Isis», or the city of the barque of Isis, underscoring the spiritual and symbolic reorientation of the capital towards the Nile. The Order of the Sophisians was explicitly formed to cater to this returning elite: veteran military leaders, Egyptologists, scientists, writers, and artists who had participated in the campaign.

The Sophisians asserted a dramatic claim regarding their origins, perpetuating a founding legend that its members had discovered secret, ancient rites and mysteries concealed within the Egyptian pyramids. They purported to have brought this rediscovered, authentic wisdom back to France to form the basis of their new Masonic system. By establishing an organization dedicated to Sophisia (Wisdom), the veterans and intellectuals effectively transformed the memory of a brutal military failure into a profound cultural acquisition and esoteric success, asserting superior knowledge over older European fraternities.

Foundation and Formal Structure

The Order was officially established in 1801 in Paris. Its imposing constitutional title demonstrates a conscious effort to fuse revolutionary state identity with ancient, esoteric authority: the Charte constitutionnelle de l'Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens établi dans les souterrains impénétrables des Pyramides de la République Française sous les auspices d'Horus, conformément aux Statuts Égyptiens et Grecs et d'après les pouvoirs transmis aux Isiarques par les Sept Sages interprètes des hiéroglyphes. This deliberate blending of the "Pyramides de la République Française" with the patronage of Horus and the authority of the "Isiarques" (priests of Isis) sought to graft ancient legitimacy onto the contemporary political structure of the French Consulate.

Despite its ambitious design and intellectual patronage, the Order had a markedly brief functional life. Most Masonic records indicate that the Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens disappeared from the fraternal scene around 1807, suggesting a lifespan of approximately six years. Although some analysis suggests its duration may have stretched to two decades, the most common consensus places its active period squarely in the initial flush of post-campaign Egyptomania.

The Cult of Isis and the Sophisian Doctrine

The philosophical and ritualistic foundation of the Sophisian Order rested heavily upon Egyptian mythology, particularly the veneration of the goddess Isis. Isis, revered as the daughter of Geb (Earth) and Nut (Sky), and the sister-wife of Osiris, represented motherhood, healing, and profound magical power. Her central myth involves resurrecting Osiris after his murder, establishing her dominion over life, death, and fate, and granting her power over creation and destruction through magical utterances.

The internal structure of the Sophisians mirrored the asserted derivation from Ancient Egyptian rites. The Order organized itself into a hierarchy analogous to the Egyptian priesthood. Local lodges were symbolically designated as "Pyramides," such as the "Pyramide" established in Toulon.

Esoteric Integration and Precedent

Like many secretive societies of the era, the esoteric doctrines of the Sophisians were guarded and revealed only to the most advanced initiates across higher degrees. The broader intellectual project of the Order was defined by its struggle to integrate divergent philosophies. It functioned as a unique philosophical crucible, attempting to unify the empirical, rational rigor of Enlightenment science (as practiced by its academic members) with the vitalistic and ancient spiritual mystique imported from Egypt.

The choice of Isis worship was a deliberate and strategic philosophical move. The cult of Isis was historically universal, having spread throughout the Mediterranean and into the Roman Empire, offering promise of eternal life and spiritual equality across diverse social classes. This tradition of universality and spiritual egalitarianism provided a conceptual justification for the Sophisians' own remarkably inclusive membership practices, particularly the initiation of women, a rarity in European Free-Masonry at the time.

Moreover, the Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens serves as a foundational precursor to the later, more structurally complex high-degree systems of Egyptian Free-Masonry. Established in 1801, the Sophisians immediately preceded the introduction of the Rite of Misraïm to France (1814) and the subsequent formation of the Ancient and Primitive Rite of Memphis-Misraïm (1881). The Sophisians, through their elaborate rituals and structural adoption of Egyptian hierarchy, clearly demonstrated the immediate post-campaign cultural demand for a formalized, purely Egyptian esoteric conduit, paving the way for these influential later Rites.

The Theatricalization of Initiation and Le Livre d'or des Sophisiens

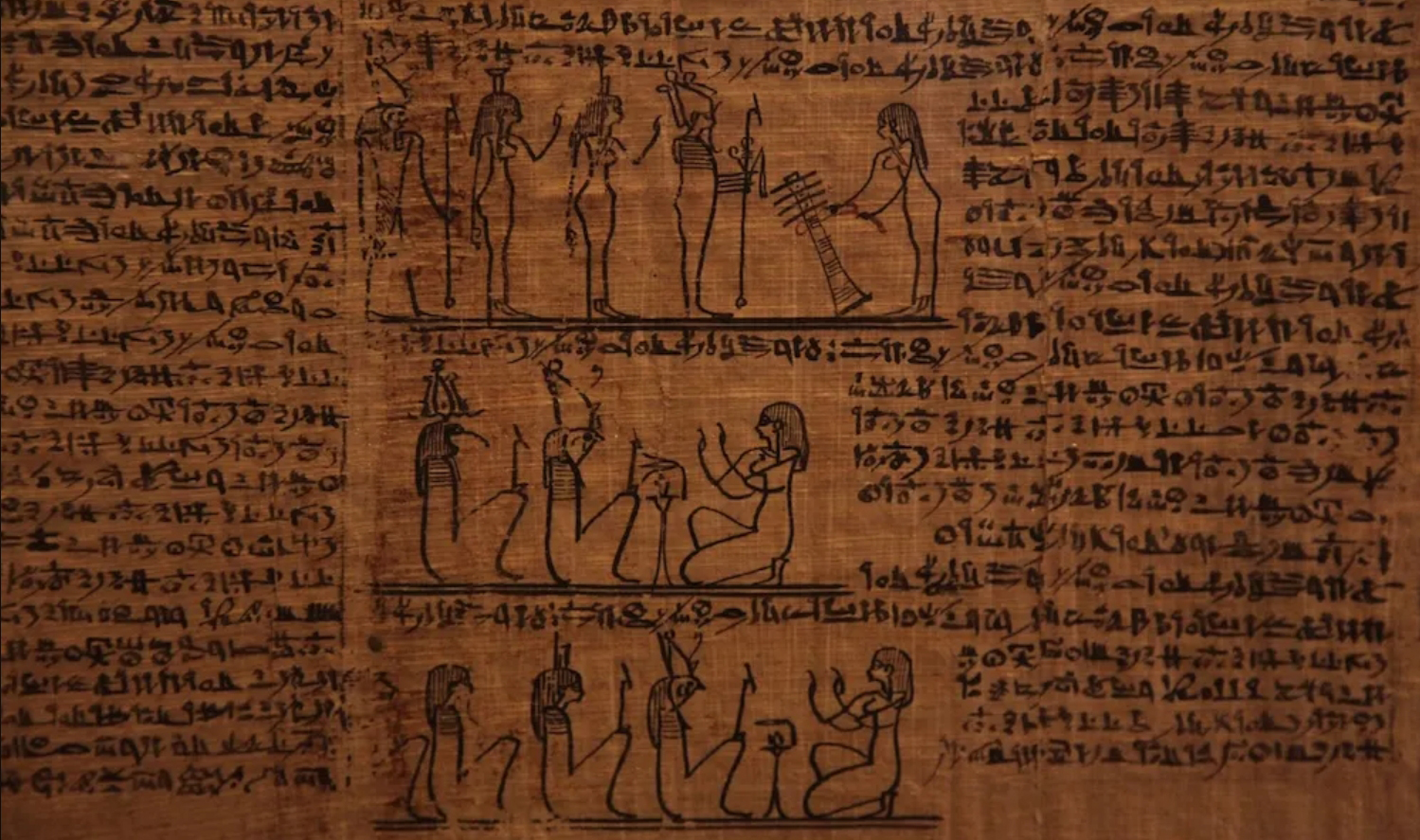

The most significant evidence documenting the Sophisians’ ritual life and aesthetic ambitions is the Golden Book (Le Livre d'or des Sophisiens). This richly illuminated manuscript is a crucial primary source, preserved among unpublished archival materials located at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) in Paris.

Art and Performance in the Ritual

The Golden Book reveals that the Sophisian initiations were designed as immersive, spectacular performances. The manuscript was conceived by Marie-Nicolas Ponce-Camus, a student of the towering figure of Neoclassical painting, Jacques-Louis David. This direct link to David’s highly influential artistic lineage underscores the sophisticated visual standards and aesthetic seriousness with which the Order approached its rituals.

The Livre d'or explicitly features detailed renderings of the theatrical settings used to recreate alleged Ancient Egyptian initiation practices. These settings included elaborate stagecraft that transformed the lodge space into:

- Underground mazes.

- Cave settings.

- Pyramids and temple structures.

Given that the founder, Cuvelier de Trie, was a professional playwright and that the membership included a large contingent of actors, composers, and producers from the Parisian boulevard theaters, the Order effectively outsourced its spiritual legitimacy to the artistic authority of the Parisian Neoclassical movement. The ritual was credible precisely because it was visually stunning and professionally staged by individuals who excelled in dramatic immersion.

The manuscript’s content includes philosophical maxims of the Order and, critically, the full constitutional charter destined for a local lodge, identified as the “Pyramide” of Toulon. The Sophisians, lacking concrete ancient documents (which they claimed to possess), relied on this sophisticated artistic rendering to visually and spatially assert the reality of their Egyptian rites.

The heavy reliance on theatrical spectacle also served a socio-political function. At a time when censorship was still enforced, the allegorical and dramatic framework of the rituals provided a safe space where veterans and intellectuals could discuss sensitive subjects, such as the disillusioning realities of the Egyptian defeat and the implications of French colonialism, without attracting government scrutiny. The secret society, therefore, leveraged the safety of ritual space for socio-political commentary.

Theatricality and Archival Data of the Sophisians

| Category | Detail | Thematic Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Le Livre d'or des Sophisiens (The Golden Book) | Documents the Order’s visual and ritual ambition. |

| Archival Location | Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), Paris | Confirms the accessibility and authenticity of primary material. |

| Visionary/Artist | Marie-Nicolas Ponce-Camus (Student of David) | Highlights the involvement of high-caliber artistic talent in ritual design. |

| Key Ritual Settings | Underground mazes, Caves, Pyramids, Temple Structures | Demonstrates the fusion of esoteric narrative with dramatic stagecraft. |

| Founder's Profession | Playwright (Cuvelier de Trie) | Provides the causal link between the Parisian stage and ritual execution. |

Membership Profile and Social Radicalism

The Sophisian Order was distinguished by its profoundly eclectic and high-profile membership roster, setting it apart from many other contemporary Masonic societies. This group represented a powerful synthesis of the era's intellectual, military, and artistic establishments.

A Coalition of Elites and Artists

The initial core of the Order was comprised of returning veterans, Egyptologists, and savants from Napoleon's Egyptian campaign. Critically, the membership included some of France’s most distinguished scientific thinkers, representing the pinnacle of the Enlightenment tradition. Notable scientific members included the mathematician Gaspar Monge and the eminent botanists Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Comte de Lacépède. The inclusion of these academic figures suggests a deliberate attempt to lend empirical authority to the Order's claims of profound Egyptian wisdom, bridging Enlightenment rationalism with vitalistic mysticism.

The membership base quickly expanded beyond the military-scientific complex, attracting a critical mass of new members from the Parisian stage. This large contingent of producers, playwrights, and actors supplied the operational expertise necessary to execute the elaborate theatrical rituals detailed in the Golden Book. The sophisticated intellectual project of the Sophisians involved the scientists providing the objective historical and empirical data gleaned from the Egyptian expedition, while the artists provided the means to experience that data via subjective, emotionally charged ritual, converting academic findings into personalized esoteric journeys.

The Order also possessed a surprising international reach, drawing members from beyond the French orbit, including professors from the University of Bucharest and, notably, a Creek Indian tribal leader.

Pioneering Inclusion of Women

Perhaps the most radical feature of the Sophisian membership was its acceptance and initiation of women, a practice highly unconventional for a Masonic body operating under the Grand Orient de France in 1801.

The most prominent example of this pioneering inclusion was the Prussian-born Mme de Xaintrailles. Already known for her military service as an aide-de-camp in the Army of the Rhine, her initiation into the Sophisians marked a significant social statement. During her ceremony, she made the highly symbolic declaration: "I am a man for my country [and] will be a man for my Brethern". This statement reveals the contradictory dynamics of gender progress in the post-Revolutionary era. While the Order was progressive in admitting women based on merit, acceptance often required the female initiate to adopt a traditionally masculine identity to gain full fraternal recognition, demonstrating that meritocracy was contingent upon transcending conventional gender roles.

Sophisian Membership Profile and Cultural Synthesis (c. 1801)

| Membership Category | Notable Examples | Significance to the Order |

|---|---|---|

| Military/Veterans | French Generals and Officers | Established the Order’s direct, physical link to Egypt and initial legitimacy. |

| Scientists (Savants) | Gaspar Monge, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Comte de Lacépède | Represented the Enlightenment’s rational framework, bridging objective science and vitalism. |

| Theater/Arts | Cuvelier de Trie (Founder), numerous actors/producers | Provided the stagecraft, visual design, and emotional intensity for spectacular rituals. |

| Women | Mme de Xaintrailles (Aide-de-camp) | Demonstrated the Order’s unusual social radicalism and egalitarian ideals. |

Legacy and Historical Context within Egyptian Free-Masonry

The formal activities of the Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens were quickly curtailed, with the Order largely disappearing from Masonic records by 1807. This rapid decline, despite the Order’s initial high-profile membership and artistic ambition, suggests that its intense focus on the immediate cultural and emotional aftermath of the 1801 Egyptian campaign may have limited its structural resilience. Once Napoleon’s regime stabilized and the initial wave of cultural Egyptomania subsided, the necessity for a specialized "safe place" for political and intellectual discourse tied directly to the campaign diminished, leading to its dissolution.

Contribution to Esoteric Rites

Despite its brevity, the Sophisians made a tangible contribution to the history of Western esotericism. By successfully developing and staging an elaborate Egyptian framework, they established a crucial cultural precedent for the formal Egyptian Masonic systems that followed. They were a vital early demonstration of the appetite among French Masons for deeply symbolic, high-degree Rites centered on the mysteries of Isis and the pharaonic past. This precedent directly influenced the later success of systems such as the Rite of Misraïm and the subsequent Ancient and Primitive Rite of Memphis-Misraïm.

The Sophisians also engaged in the highly competitive environment of early 19th-century French Free-Masonry by asserting a superior historical lineage. While they operated under the umbrella of established French Rites, their constitutional claims of powers transmitted directly "under the auspices of Horus" and by "Isiarques" represented an attempt to use the exotic spectacle of Egyptomania to claim an older, more authoritative source of wisdom than the European Rites, such as the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite.

Enduring Significance

Ultimately, the importance of the Ordre Sacré des Sophisiens is conceptual and cultural rather than structural. The meticulous academic study of the Sophisians, relying on primary documents such as Le Livre d'or, provides a unique lens for understanding the intellectual landscape of Napoleonic France. The Order epitomized the era's negotiation of vast cultural and philosophical contradictions: the difficulty of implementing colonial power while maintaining a façade of a civilizing mission, and the complex balance required between Enlightenment rational inquiry and a renewed, profound hunger for mysticism and ancient secret knowledge. The survival and accessibility of the richly illustrated manuscript, detailed in historical catalogs and preserved at the BnF, ensure that the Sophisians remain a critical subject for historians analyzing the theatrical and artistic expressions of early 19th-century Western Esotericism.

Article By Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴